When did the Magnus Carlsen era begin?

Good question. When did the Magnus Carlsen era begin? In 2004 when he became a grandmaster at the age of 13? In 2010 when he first topped the world rankings? Or in 2013 when he defeated Vishy Anand to become World Champion?

If we turn the clock back exactly 10 years, it’s not hard to remember the feelings of excitement and anticipation we all had about Magnus’s ultimate breakthrough. Vishy Anand was still World Champion, having defended his title successfully earlier in the year against Boris Gelfand in Moscow, but his next Challenger would be the winner of the Candidates tournament in London in March 2013. And few doubted that Magnus Carlsen was ready to take the final two hurdles to the highest title.

Magnus’s big test before the Candidates was the Tata Steel Tournament in Wijk aan Zee, the ‘Wimbledon of Chess’ that he had already won twice. Just like we are now looking forward to the 85th anniversary tournament, we were then eagerly awaiting the 75th edition. An edition that didn’t disappoint, and neither did Magnus. Remaining unbeaten the Norwegian equalled Garry Kasparov’s record score of plus-7 to finish one and a half points ahead of Levon Aronian and two points ahead of Vishy Anand and Sergey Karjakin.

That’s what he did in the first month of 2013. Next in March he won the Candidates tournament in a breath-taking head-to-head race with Vladimir Kramnik. Finally, in November, in Chennai, India, he became World Champion, eight days before his 23rd birthday.

It's interesting to reread the thoughts and emotions that his win in Wijk aan Zee, in January 2013, evoked and how I described my impressions in New In Chess Magazine.

Additionally, there are two games from that report that you will certainly enjoy.

Magnus’s notes to the win he was most satisfied about (Carlsen - Sokolov) and a brilliant game by the man who was still the reigning World Champion. A masterpiece by Anand that Carlsen magnanimously (and rightly, of course) called ‘one for the ages’. (Aronian - Anand)

Read the full report from New In Chess magazine 2013#2 below or check out the pdf: 2872, but not there yet

The 75th Tata Steel Chess tournament ended in a sweeping victory for Magnus Carlsen. With seven-league strides the world’s number one raced through the jubilee edition to a baffling plus-seven, equalling the record score with which Garry Kasparov demolished the field in his Wijk aan Zee debut in 1999. Carlsen finished one and a half points ahead of fellow-Candidate Levon Aronian and a full two points ahead of World Champion Vishy Anand and Sergey Karjakin. The Norwegian looked back on a clean race: ‘I managed to win all the games in which I had an advantage at some point, and to draw all the games in which I was doing badly.’ In the process he took his rating to a new all-time high of 2872, leaving Vladimir Kramnik gasping in second place at a 62-point distance. Yet, Carlsen is fully aware that with the long-awaited next big challenge around the corner he should not lose his sense of fear: ‘I hope for the Candidates’ that my openings will be a little bit better and my general play quite a bit sharper.’

As Magnus Carlsen was showered with praise, his fans and the press had a wealth of records and statistics to choose from to underline the weight of his historic victory. His third win in Wijk aan Zee was his first super-tournament that he won with a plus-seven score. And although he ‘only equalled’ Kasparov’s monster score of 1999, his 10 points from 13 games (a 2933 performance) pushed his rating to heights where no one has ever been, 21 points higher than Kasparov’s seemingly untouchable peak of 2851, reached in 2000.

One achievement that was not mentioned, probably because he failed to win his last-round game, was the fantastic streak he had had before that day. From the 25 games he played in the second leg of the Grand Slam Final in Bilbao, in the Classic in London and in Wijk aan Zee up to that game, he had gathered a stupendous 20 points (15 wins and 10 draws), a unique feat at this level.

Certainly noteworthy as well was the fact that in all nine previous appearances in Wijk aan Zee, Carlsen had lost at least one game and that this was the first time he remained unbeaten. Even in his sensational debut in the C-Group in 2004, when he scored 10½ from 13(!), he lost one game. The answer to the pub quiz question who was his opponent in that game, is Dusko Pavasovic, the Slovenian GM, who, at 2615, was the top-seed that year. (The answer to the next pub quiz question is: 13-year-old Magnus Carlsen was still an IM and at 2484 he was the eighth seed.)

Carlsen’s 10th consecutive appearance coincided with the 75th anniversary of the greatest chess festival in the world. In the months leading up to the Tata Steel tournament there had been nervous speculation about the future of this unique event. Not without reason, as behind the scenes the organizing committee was fighting hard to keep the tradition alive. Only at the official opening were worries dispelled with the announcement that next year there will be a 76th edition. Wonderful news indeed.

His third win in Wijk aan Zee, plus 7, undefeated, a new Elo record... What more could Magnus Carlsen and his manager Espen Agdestein have hoped for?

His third win in Wijk aan Zee, plus 7, undefeated, a new Elo record... What more could Magnus Carlsen and his manager Espen Agdestein have hoped for?

Magnus Carlsen feels that his number one position comes with the responsibility to lead the life of a top professional in which an eye for detail is essential. While contemplating his preparation for Wijk aan Zee he didn’t want to repeat the mistake he made last year, when he ran out of steam way before the end and saw his hopes of first place go up in smoke after a loss to Sergey Karjakin in Round 9. His conclusion was that last time his sun holiday before wintry Wijk aan Zee had not been sunny enough. In order to stow enough vitamin D to last 13 long rounds he travelled to Jordan this time. There he prepared physically and mentally in a luxurious resort in the Gulf of Aqaba in the company of his family.

Carlsen’s purposeful preparation was in stark contrast with the approach of bottom seed Hou Yifan to her debut in the top group. The former Women’s World Champion took five exams at Beijing University, where she is studying International Relations, the last of them one day before she boarded the plane to the Netherlands. Remarkably, she also arrived without a second, because the Chinese chess federation had no one available to accompany her. Instead she relied on her steady companion, her mother Wang Qian, a trained nurse with no specific chess knowledge. In the first rounds Hou Yifan had a rough time, but true to her character she kept fighting for her chances. In the end she won three games and could look back on a satisfactory debut with a 2685 performance.

A good part of Carlsen’s success can be attributed to his physical fitness. Even after long and tense games he would get up looking fit as a fiddle and ready for the next fight. On the free days he made sure he didn’t miss the football games to let off steam. His fitness and his unusual gift for the game remain the basis of what has become his trademark style. Acknowledging that these days getting an advantage from the opening is well-nigh impossible, as everyone relies on top-notch computers for research, he tries to reach positions in which he is confident that he will outplay his opponents in the middle- or endgame.

A good part of Magnus Carlsen’s success can be attributed to his physical fitness. On the free days he made sure he didn’t miss the football games to let off steam. As Carlsen breaks away, another fanatic, Loek van Wely, looks determined to stop the Norwegian.

His successes have brought him many admirers, but inevitably there are detractors as well. In an interview with Evgeny Surov of chess-news.ru, Evgeny Sveshnikov criticized Carlsen’s play, saying that he certainly is a practical player, but that his weakness is the openings. If he doesn’t switch to a scientific approach, in the footsteps of people like Polugaevsky and Kasparov, Sveshnikov believes that his ‘future doesn’t look so promising’.

Indeed, you can’t please them all! When not so long ago chess preparation began to take on ridiculous proportions, some people predicted the death of the game because ‘originality’ and ‘real chess skills’ were playing an ever less prominent role. Now that a new trend has developed thanks to Carlsen and let’s not forget Levon Aronian, one would have expected everyone to be happy, as they show that chess continues to be rich with mystery in all phases of the game.

Sveshnikov’s words left Carlsen fairly indifferent when he was confronted with them. Shrugging his shoulders, he commented: ‘I think everyone is entitled to their opinions. He’s entitled to his, that I should have a more traditional approach and that Karjakin has better championship prospects.’ And then with a laugh: ‘And I am entitled to my opinion that he’s a grumpy old man.'

Carlsen’s start was hesitant. He drew his first two games and he was lucky to survive a highly suspect position against Aronian. His first win followed in Round 3. With nine decisive games, including four wins, Loek van Wely provided a lot of entertainment in this jubilee edition, but his opening play against the number one led to a quick disaster. Carlsen barely spent any time and after 33 moves Van Wely resigned.

Vishy Anand also scored his first win in Round 3, at the expense of Fabiano Caruana. The World Champion remains highly popular in Wijk aan Zee (he won here for the first time in 1989!) and his early success was welcomed with approval. But these nods and smiles were nothing compared to what happened in Round 4, when Anand composed a masterpiece in his game against Aronian. A game that Carlsen called ‘one for the ages’. In a complex Meran, Anand introduced a new concept and followed up with a number of brilliant punches that left everyone in raptures. As Anand was the first to point out in the press conference, the game bore a remarkable resemblance to the legendary attack that Rubinstein conducted against Rotlevi in 1907. Here the answer to the pub quiz question with what dashing move that game ended is: 25...♖h3!

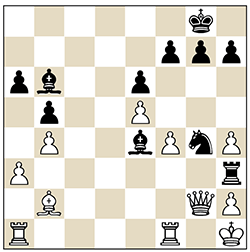

Rotlevi-Rubinstein

Lodz 1907

And White resigned in view of 26.♖f2 ♗xf2 27.♕xe4 ♖xh2 mate or 26.♖f3 ♗xf3 27.♕xf3 ♖xh2 mate.

Comparing brilliancies from such different eras is a fairly useless exercise. For Rubinstein it was ‘easy’ to start great complications and emerge victorious, as his opponent was a much weaker player, whereas Anand played the number two player in the world. He had to work out most of his attack at the board, but on the other hand he had studied the concept and knew that the situation was favourable for Black. Maybe we shouldn’t enter this discussion and simply enjoy both games for the beauty they offered.

In the shadow of Anand’s showpiece, Carlsen won a fine game against Harikrishna, to move into the shared lead. The third leader was Sergey Karjakin, who proved highly efficient against the two Chinese participants. In Round 1 the Russian treated himself to a birthday present by beating Hou Yifan, two days later he also defeated Wang Hao.

This trio remained in the lead in Round 5, when all three drew their games. To everyone’s disappointment, the big clash between Anand and Carlsen was a fairly insipid affair for non-chess reasons. Carlsen had been ill during the night and, running a fever, he felt unable to play only one and a half hours before the game. Fortunately, the pills that the tournament doctor provided worked a small miracle, and during the game he was feeling ‘a little better’. It must have been the first time in quite some time that the Norwegian arrived at the board aiming to make a draw. The game will not find its way into any games collection, but he achieved his goal. ‘It was not so much fun to be playing at 40 per cent of my capacity. I mean, I could calculate variations, but it was just taking very long. That was why I was trying to play something extremely simple and be as safe as possible.’

The next day he was sufficiently recovered to take the sole lead. Ivan Sokolov opted for one of those lesser known Ruy Lopez variations that he has written about so eloquently in The Ruy Lopez Revisited, and that he knows so well. Once again the Dutchman proved the validity of his choice and reached a perfectly satisfactory position. But it was not enough. As he describes in his illuminating notes to the game further on, Carlsen kept looking for his chances and found them with microscopic precision.

In the meantime, Levon Aronian was recovering admirably from his loss against Anand. Which perhaps wasn’t that remarkable, as such hopeless defeats tend to leave fewer scars than well-played games that are spoiled by a silly blunder. As Aronian put it philosophically: ‘It was a great find, it took him a long time, I guess. And even if it took him a short time, it was great homework. It was good that I didn’t see this in London.’

Aronian immediately bounced back with wins against Sokolov and Leko. These two wins inspired a great run of 6 out of 7 following his loss to Anand. Much to his chagrin, this run ended after his fine win against Nakamura in Round 11. Aronian felt that he still had chances to repeat his tournament victory of last year, but he only managed two draws in the final two rounds.

Another happy winner in Round 6 was Hou Yifan. Her opponent, Anish Giri, may have felt that the moment had come to play for a win after a protracted series of five draws, but the opposite happened. The Dutch favourite would have to wait till Round 11 for his first and only win. Ironically, his victim was Fabiano Caruana, who fell ill in the final week and played his worst tournament in ages. The Italian has Vladimir Chuchelov as trainer, but could not rely on the services of the Belgian grandmaster in Wijk aan Zee, as Chuchelov accompanied another of his charges there... Anish Giri. The young Dutchman only showed his true potential in the last three rounds, with this win and good draws against Aronian and Carlsen. Said Carlsen: ‘I think he’s been playing at the level he should be playing in the last three rounds. Maybe he suddenly discovered that the tournament had started.’

And what about Anand? He was doing fine, too. In Round 7 he joined Carlsen in the lead again, when he fairly effortlessly disposed of Van Wely, while his rival had to defend a long endgame against Peter Leko.

Leko worked hard and showed further progress since his comeback after a one-year break. The Hungarian finished in fifth place and suffered only one loss. In Round 10 he provided a sample of his profound opening preparation that left his opponent Ivan Sokolov speechless.

The tournament was essentially decided in Rounds 8 to 10, when Carlsen broke away with a hat-trick that gave him a one and a half point lead over Anand, Aronian and Nakamura.

The three wins were vintage Carlsen and two of them are analysed in Jan Timman’s column further on. The top-seed was still full of energy, showing no signs of fatigue whatsoever. Typical was his win in Round 8 over Karjakin. Last year his loss against the same opponent in Round 9 had been a first sign that he didn’t have the strength to show his best in the final rounds. This time there were no such signs. With endless energy and ingenuity Carlsen fought on in a level endgame and got his reward after 92 moves. As Karjakin, deathly pale, almost stumbled out of the hall, Carlsen got up with a grin, looking as if he could easily have played on for several more hours.

The next day, Carlsen was working late again. All boards in the A- and B-Groups had already been deserted when, on an empty stage, Hou Yifan ceased her resistance after 66 long moves. Together with the 65 moves he needed the next day to beat Erwin l’Ami, Carlsen produced a total of 223 moves in these three decisive rounds, convincing proof that there was nothing wrong with his vitamin D level.

Despite this demonstration of strength, with three rounds to go miracles were still possible, even if they were not very likely to happen. Carlsen had some tricky hurdles left, while Anand in particular had a lighter programme. The miracle didn’t happen. Carlsen survived dubious positions against Wang Hao and Giri and clinched tournament victory with one round to spare, when he punished Nakamura’s risky play in Round 12.

Nakamura was understandably upset with yet another loss to Carlsen, but tried to explain it objectively. ‘If I play bishop f6 instead of knight g2, it’s very difficult to assess the game. A computer would win that position very easily with either colour against one of us. I think overall Magnus just understood the structure a little bit better.’ His overall assessment of his result was similar: ‘I felt like I played a couple of good games throughout and I was able to convert them, but overall the quality of my play was quite poor. To finish on plus 1 is something of a miracle considering how many bad if not losing positions I had throughout the tournament. I just didn’t play well here. But sometimes you just have to have some bad results and learn from them and move on to the next tournament.’

By that time Anand had spoiled his last chances when he failed to convert a winning position in Round 11 against Hou Yifan with a most unusual mistake.

On the final day Anand’s fate was even worse. Against Wang Hao he suffered his first loss in the tournament, leaving Carlsen as the only undefeated player. Anand was at a loss about his play on the final day: ‘Every once in a while I play a game that I cannot explain in any logical way. I mean, on days when you make 10 positional blunders in a row, you’re just doomed to lose and there is no point in trying to explain it. If not for this game, it would still be a nice event. Well, what can I say? I spoilt it. But still overall I will go with some positive feelings. Plus 3 is different from what I was doing for a while. But it’s unfinished somehow...’

Levon Aronian was also in a sombre mood after his last game, blaming himself for letting Caruana escape with a draw from a totally lost position. Still, the half point he was left with was good enough for sole second place. His conclusion was also one of mixed emotions: ‘I’d been looking forward to finally playing again after London. I was so eager to play. Chess is the kind of game that after you played a bad tournament you really want to play. The next day! That’s what I felt, and even though I started slowly I still could tell that I was playing well. This was a tournament of missed opportunities. I think I could have scored more points. But there are never excuses, I don’t like using them. I should pay attention to that, to keep my concentration.’

Inevitably, he also saw his performance in light of the upcoming Candidates’ tournament. ‘Yeah, I thought about it, 2012 was a different year. I was trying to play more aggressively, pushing for my limits. This year I’ve decided to return to my usual self, you know. Playing and attempting to satisfy my positional sense. Not pushing into all kinds of tactics, trying to get rid of my hot-headedness. It was a good tournament, with the exception of the game against Anand. In all other games I had reasonable positions and I could have scored more points. I look at the future and I think, this is the moment to show what I’ve got.’

Sergey Karjakin, who shared third place with Anand, was the fourth player to go through the tournament with only one loss. Despite this loss against Carlsen, Karjakin was not in the mood to complain. ‘Basically, I am quite satisfied, because I had a few bad games. Against Aronian I was completely lost and I was lucky to escape. With such luck plus three is quite a good result.’ To which he added laughing: ‘In 2009 I also scored plus 3 and I was clear first!’

The last night was great fun, with Magnus Carlsen taking on all comers (in this case Hou Yifan) in the bar of the Zeeduin Hotel. Sergey Shipov is visibly happy with his ringside seat.

The last night was great fun, with Magnus Carlsen taking on all comers (in this case Hou Yifan) in the bar of the Zeeduin Hotel. Sergey Shipov is visibly happy with his ringside seat.

And easily happiest, of course, was Magnus Carlsen. Immediately after the last round he could not suppress his annoyance about his play on the final day, which had kept him from breaking Kasparov’s record, but quite soon he admitted that in a couple of days’ time that nagging voice inside would shut up and allow him to enjoy this win for what it is. Perhaps as his finest victory ever, although he probably still rates his stellar performance in Nanjing 2009, where he scored 8 out of 10 (TPR 3002) and crossed the 2800 barrier, a little bit higher: ‘That was kind of my breakthrough and I also was a much weaker player then than I am now.’

After London you said it was time to take your game to another level. Did we see any of that here?

‘No. I did pretty much the same as I did in London and Bilbao. I just think it sometimes is going to net me plus 3, plus 4, and sometimes plus 6, plus 7.’

And taking it to another level would be more perfectionist.

‘Yes.’

The Candidates’ tournament would be a good occasion then. Were you hiding anything here?

‘Yeah, you know... partly, but it was just about... Especially some of the positions I got with black, they were not necessarily bad, but I was not so familiar with them and I misplayed them pretty early on. So then the games became something of an uphill struggle. I thought with white my openings were fine. I don’t expect to get too much of an advantage, but I got a lot of good fighting positions.’

I think one of the problems you have now is that you played so well in the past tournaments, that it might affect your sense of fear. Is that something you worry about yourself?

‘Yeah, maybe a little bit. I mean, I am kind of used to that, whenever I get a slightly better position, I almost always win. And when I am slightly worse, I never have any problems holding it, so ... Right now I am close to where I need to be, but not right there. I hope for the Candidates’ that my openings will be a little bit better and my general play quite a bit sharper and then I am going to be right there.’