A monstrous Keres project

Now past fifty, Matthew Sadler finds himself looking backward as much as forward – and correcting a few false assumptions. His most recent reappraisal was prompted by a 4,013-page project on Paul Keres.

These book reviews by Matthew Sadler were published in New In Chess magazine 2025#4

As I head towards my fifty-second year on this earth, I have the strange sensation of looking backwards as much as forwards. Plans for the future are tinged with a hint of melancholy because I’ve become aware that my life path has made some dreams very unlikely to happen. It’s the chess player’s equivalent of staring forlornly at your black pieces at move 30 and thinking, ‘What possessed me to play the Czech Benoni?’

I don’t have too many regrets about the mistakes I’ve made in life, because life is something you figure out as you go along and accidents are bound to happen. However, I have felt quite irritated about some of the mistakes I’ve made in chess – strangely enough, not so much about the blunders I made during tournament games as the errors of understanding I made while training myself.

Looking at developments in modern chess, I often wonder how I could have been so blind as a professional! How could I have spent weeks on certain positions in the 90s and not even come close to finding the right idea? For example, take this typical structure from the Queen’s Gambit Accepted:

Stockfish 8 – AlphaZero

London computer match 2018

Queen’s Gambit Accepted

1.♘f3 ♘f6 2.d4 d5 3.c4 e6 4.e3 b6 5.♗d3 ♗b7 6.0-0 dxc4 7.♗xc4 a6 8.♘c3 b5 9.♗b3 c5 10.e4 cxd4 11.♘xd4 ♘bd7 12.♖e1 As a professional, I once dedicated a few weeks to analysing such structures in a variety of settings. I came to the conclusion that the advance of White’s pawn to e4 contained the seeds of White’s downfall! My pieces should dance on the dark squares around the e4-pawn – e5, f4 and d4 – and by doing so, I should tempt out the move g3 from White (to cover the f4-square). Once g3 has happened, White’s solidity along the long diagonal is lessened by the weakness of f3, which will give me the next set of ideas to punch holes in White’s position. I came up with all sorts of manoeuvres to attack the f4-square with my pieces and tried to understand the advantages and disadvantages of each. I was very pleased with this work, felt I understood these positions really well, and indeed scored some valuable points with this knowledge. And then some years ago, I noticed this game between Stockfish 8 and AlphaZero (analysed in depth in The Silicon Road to Chess Improvement).

As a professional, I once dedicated a few weeks to analysing such structures in a variety of settings. I came to the conclusion that the advance of White’s pawn to e4 contained the seeds of White’s downfall! My pieces should dance on the dark squares around the e4-pawn – e5, f4 and d4 – and by doing so, I should tempt out the move g3 from White (to cover the f4-square). Once g3 has happened, White’s solidity along the long diagonal is lessened by the weakness of f3, which will give me the next set of ideas to punch holes in White’s position. I came up with all sorts of manoeuvres to attack the f4-square with my pieces and tried to understand the advantages and disadvantages of each. I was very pleased with this work, felt I understood these positions really well, and indeed scored some valuable points with this knowledge. And then some years ago, I noticed this game between Stockfish 8 and AlphaZero (analysed in depth in The Silicon Road to Chess Improvement).

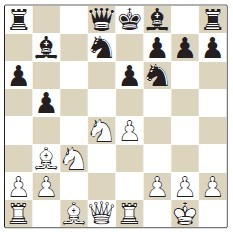

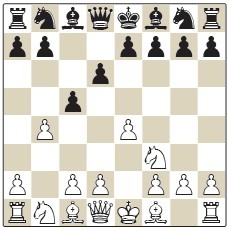

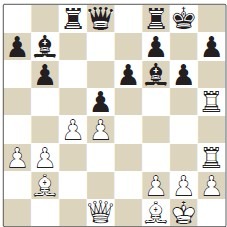

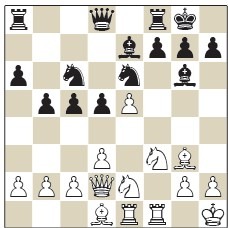

12...♘e5 13.♗f4 ♘g6 14.♗e3 ♗b4 15.f3 0-0 16.a4 bxa4 17.♖xa4 ♕e7 18.♕e2 a5 19.♗c4 19...h5

19...h5

Yes, it’s that easy! AlphaZero simply wants to weaken White’s control of the kingside light squares by marching the h-pawn all the way to h3.

20.♘c2 ♗d6 21.♖ea1 ♖fc8 22.♕d2 h4 23.♘b5 ♗c5 24.♗xc5 ♖xc5 25.♗d3 ♖d8 26.♖d4 h3 27.g3 ♘e5 That’s exactly what I was looking for. In fact, it’s way better, because the h3-pawn also restricts the mobility of the white king and fixes a weakness on h2 for the endgame. Both of these factors were of decisive importance in this game.

That’s exactly what I was looking for. In fact, it’s way better, because the h3-pawn also restricts the mobility of the white king and fixes a weakness on h2 for the endgame. Both of these factors were of decisive importance in this game.

Weeks of serious work, and this concept never occurred to me. I guess I had so much inner resistance to pushing pawns in front of my castled king, that the thought of achieving my dream in the most efficient manner by launching the h-pawn never entered my mind. The frustration lies particularly in the fact that I’m knowledgeable enough to appreciate the idea. When I saw it, I knew at once exactly why it was powerful.

The same feeling has overwhelmed me quite often in the past few years when revisiting the games of classic players. It started in 2016, when by coincidence I started analysing Efim Bogoljubow’s games and discovered to my surprise that he was a far better and more interesting player than I had ever imagined. Rather shockingly, this same pattern has now repeated itself many times over (for example, with players like Tarrasch, Janowski and Teichmann) and books like Willy Hendriks’ wonderful The Ink War and The Philosopher and the Housewife haven’t made me feel any better! Essentially, I’ve spent most of my chess life with totally inaccurate assumptions about many (most even!) of the players that have gone before me.

Does it matter? Well, that’s the million-dollar question! I suspect that I’ve missed hundreds of learning opportunities simply because I chose a view of chess history that excluded certain players as irrelevant, mostly because they didn’t become World Champions.

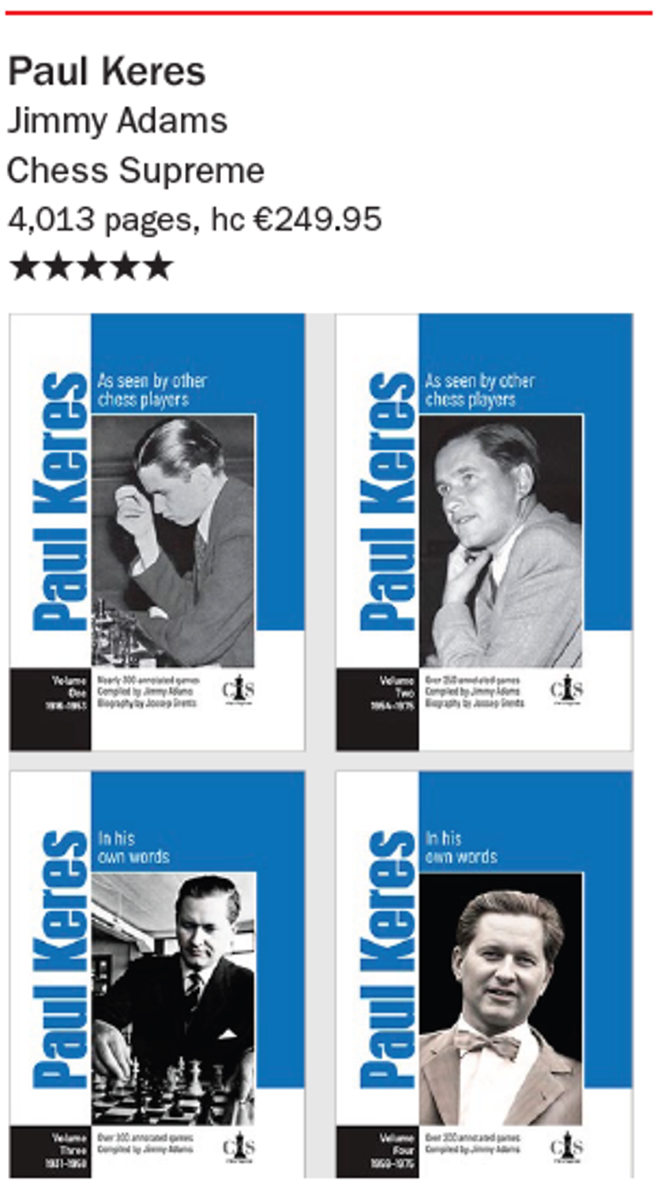

That feeling struck me once again when reading Jimmy Adams’s monster four-volume hardback 4013-page compilation of the games of the great Estonian player Paul Keres (1916-1975). Sigh, here we go again, another player to whom I’ve devoted remarkably little attention until now. My feelings about Keres revolved around two tournament books that I read as a child. The first was The Lost Olympiad: Stockholm 1937 by WH Cozens, which I read to pieces as a child. He wasn’t in his most sparkling form at that tournament, but Cozens talked about him a lot as a dashing attacker in the romantic style reinforced by miniatures like this:

That feeling struck me once again when reading Jimmy Adams’s monster four-volume hardback 4013-page compilation of the games of the great Estonian player Paul Keres (1916-1975). Sigh, here we go again, another player to whom I’ve devoted remarkably little attention until now. My feelings about Keres revolved around two tournament books that I read as a child. The first was The Lost Olympiad: Stockholm 1937 by WH Cozens, which I read to pieces as a child. He wasn’t in his most sparkling form at that tournament, but Cozens talked about him a lot as a dashing attacker in the romantic style reinforced by miniatures like this:

Paul Keres - Storm Herseth

Stockholm Olympiad 1937

Sicilian Defence, Wing Gambit Deferred

1.e4 c5 2.♘f3 d6 3.b4 A Keres patent, delaying the Wing Gambit until Black has played ...d6, which makes striking back in the centre with ...d5 less likely.

A Keres patent, delaying the Wing Gambit until Black has played ...d6, which makes striking back in the centre with ...d5 less likely.

3...♘f6 4.bxc5 ♘xe4 5.cxd6 ♘xd6 6.♘a3 ♕c7 7.♗b2 ♗g4 8.♗e2 ♘d7 9.0-0 ♘f6 10.c4 ♗d7 11.♖c1 ♖d8 12.c5 ♘c8 13.♘b5 ♗xb5 14.♗xb5+ ♘d7 15.♘e5 h5 16.♕b3 e6 17.c6 bxc6 18.♖xc6 ♕b7 19.♖xe6+ 1-0.

19.♖xe6+ 1-0.

Not a distinguished game by Black, but fun all the same! But then that image of Keres’s play hit Harry Golombek’s World Chess Championship 1948 and the Keres at that tournament disappointed 11-year-old me terribly, in particular the games against Botvinnik. This famous Nimzo-Indian made a big impression on me:

Mikhail Botvinnik - Paul Keres

The Hague/Moscow World Championship tournament 1948

Nimzo-Indian Defence, Sämisch Variation

1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 e6 3.♘c3 ♗b4 4.e3 0-0 5.a3 ♗xc3+ 6.bxc3 ♖e8 7.♘e2 e5 8.♘g3 d6 9.♗e2 ♘bd7 10.0-0 c5 11.f3 cxd4 12.cxd4 ♘b6 13.♗b2 exd4 14.e4 ♗e6 15.♖c1 ♖e7 16.♕xd4 ♕c7 17.c5 dxc5 18.♖xc5 ♕f4 19.♗c1 ♕b8 20.♖g5 ♘bd7

14.e4 ♗e6 15.♖c1 ♖e7 16.♕xd4 ♕c7 17.c5 dxc5 18.♖xc5 ♕f4 19.♗c1 ♕b8 20.♖g5 ♘bd7 21.♖xg7+ ♔xg7 22.♘h5+ ♔g6 23.♕e3 1-0.

21.♖xg7+ ♔xg7 22.♘h5+ ♔g6 23.♕e3 1-0.

That was enough to convince me to turn my adulation to Botvinnik and forget all about Keres! And now, forty years later, I’m reading through Keres’s own annotations to his games and thinking ‘my goodness he was so strong’ and feeling quite miserable about my judgement yet again!

As I mentioned before, this series is divided into four volumes. The first two volumes collect together games of Keres annotated by other players, which means that they include many losses and draws. These volumes also feature an extensive biography by Joosep Grents, which I found absolutely fascinating. The last two volumes feature games annotated by Keres himself, containing a modernised and corrected version of Keres’s own 100 Selected Games as well as many other annotations from a huge range of sources. The fourth volume ends with a complete set of tournament tables and details.

I found Joosep Grents’s account of Keres’s early chess development to be quite remarkable. Growing up in Pärnu, a provincial location as far as chess activity was concerned, Paul’s early chess was limited to games against local amateur players and his own obsessive study until a friend suggested he try his hand at correspondence chess. This was the making of him. As Keres explained: ‘I used correspondence games, above all, for experimental purposes, often opting for risky opening lines and attempting, at all costs, to create complicated positions which I could use to train my tactical skill. It is easy to notice a bias toward tactics in these games while there are still considerable problems apparent in solving strictly technical problems.’ Later Keres also joked that he had to play this way to save money on stamps. There is indeed a lot of experimentation in these games: we come across lines like 1.g4 and 1.♘f3 d5 2.e4 as White with a major role reserved for my all-time favourite King’s Gambit line:

1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.♘c3 ♕h4+ 4.♔e2 In fact, we come across super-accelerated attacking schemes in all types of openings such as this one that appealed to me a lot:

In fact, we come across super-accelerated attacking schemes in all types of openings such as this one that appealed to me a lot:

Paul Keres - Blum

Deutsche Schachzeitung 133-A corr 1932

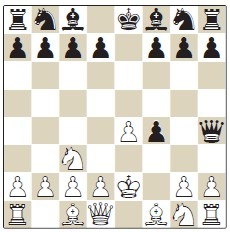

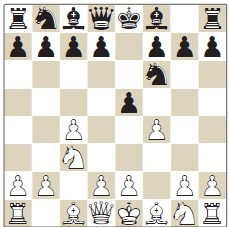

1.♘f3 ♘f6 2.b3 d5 3.♗b2 e6 4.e3 ♗e7 5.♘e5 0-0 6.f4 b6 7.♗d3 ♗b7 8.0-0 c5 9.♖f3 ♖e8 10.♖h3 g6 11.♕e1

5.♘e5 0-0 6.f4 b6 7.♗d3 ♗b7 8.0-0 c5 9.♖f3 ♖e8 10.♖h3 g6 11.♕e1 To be honest, Keres’s correspondence games look pretty much like bullet chess to a modern eye!

To be honest, Keres’s correspondence games look pretty much like bullet chess to a modern eye!

You can imagine how it must have felt for a 19-year-old to be thrust from this type of chess environment into the cauldron of the 1935 Warsaw Chess Olympiad, facing super-class players like Alekhine and Flohr as Board 1 for Estonia. Indeed, none of the Estonian team had ever played a game of chess on foreign soil before this event! In fact, Keres acquitted himself brilliantly, scoring 12 points from 19 games, the fifth-best score on top board. Keres wrote in his 100 Selected Games that ‘the most important victory for me in the tournament was convincing myself that it was indeed possible to compete successfully against the leading international players. To achieve this, in the first place I had to acquire more tournament experience and attend to my further chess development, in particular with regard to purely technical matters.’ It’s quite amazing in fact to compare this young 19-year-old with the refined positional style and superb endgame technique of which Keres was capable in the post-war years. In his chapter on Paul Keres in the also superb Learn from the Legends 2 (Quality Chess) Mihail Marin suggests that ‘Paul Petrovich was an exponent of the classical school. He used to orientate his actions according to such positional notions as space, the centre, time and development. At the same time, Keres was a highly dynamic player. After completing his development according to the classical patterns, he would use the first opportunity to stir up huge complications, allowing him to use his calculating and attacking skills. Developing the ideas above I would say that Keres’s style was marked by duality from more than one point of view. He could attack in static or in dynamic positions. He could base his thinking process on either accurate calculation or intuition. While these attributes characterise him as a universal player, they must have also created some practical problems. The richer one’s arsenal is, the more difficult it is to choose the right weapon at a particular moment.’

It’s quite amazing in fact to compare this young 19-year-old with the refined positional style and superb endgame technique of which Keres was capable in the post-war years. In his chapter on Paul Keres in the also superb Learn from the Legends 2 (Quality Chess) Mihail Marin suggests that ‘Paul Petrovich was an exponent of the classical school. He used to orientate his actions according to such positional notions as space, the centre, time and development. At the same time, Keres was a highly dynamic player. After completing his development according to the classical patterns, he would use the first opportunity to stir up huge complications, allowing him to use his calculating and attacking skills. Developing the ideas above I would say that Keres’s style was marked by duality from more than one point of view. He could attack in static or in dynamic positions. He could base his thinking process on either accurate calculation or intuition. While these attributes characterise him as a universal player, they must have also created some practical problems. The richer one’s arsenal is, the more difficult it is to choose the right weapon at a particular moment.’

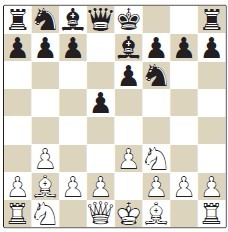

I like this term ‘duality’ very much and the interesting analysis, though I’m not sure it quite hits the mark for me. My take on it is that Keres’s early immersion in hyper-sharp correspondence chess perhaps ‘disformed’ his chess intuition a little, pushing it into the realm of the over-sharp and essentially unsound. To become a world-class player, he chose to rein himself in – in essence, to override the moves his hand wanted to make – and managed this partly by choosing exceptionally classical variations like the black side of the Lopez. At least, that’s how I explain the strange situations where in moments of stress, Keres reverted to type, such as the famous gloriously failed hack against Smyslov in the critical final phases of Zurich 1953.

Paul Keres - Vasily Smyslov

Zurich Candidates Tournament 1953

Queen’s Indian Defence

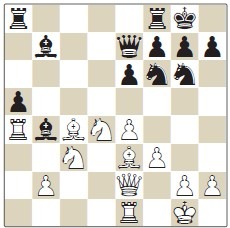

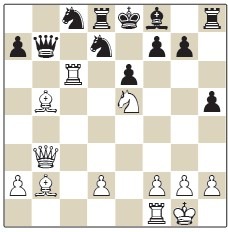

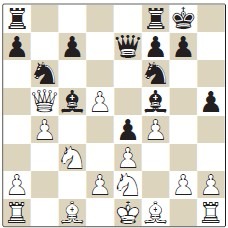

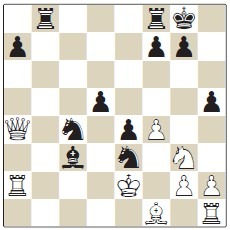

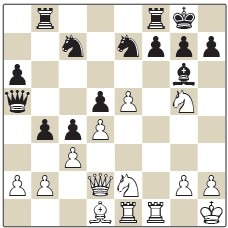

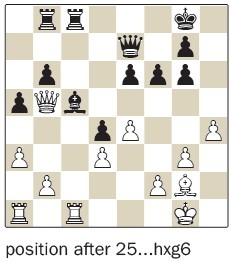

1.c4 ♘f6 2.♘c3 e6 3.♘f3 c5 4.e3 ♗e7 5.b3 0-0 6.♗b2 b6 7.d4 cxd4 8.exd4 d5 9.♗d3 ♘c6 10.0-0 ♗b7 11.♖c1 ♖c8 12.♖e1 ♘b4 13.♗f1 ♘e4 14.a3 ♘xc3 15.♖xc3 ♘c6 16.♘e5 ♘xe5 17.♖xe5 ♗f6 18.♖h5 g6 19.♖ch3 19...dxc4 20.♖xh7 c3 21.♕c1 ♕xd4 22.♕h6 ♖fd8 23.♗c1 ♗g7 24.♕g5 ♕f6 25.♕g4 c2 26.♗e2 ♖d4 27.f4 ♖d1+ 28.♗xd1 ♕d4+ 0-1.

19...dxc4 20.♖xh7 c3 21.♕c1 ♕xd4 22.♕h6 ♖fd8 23.♗c1 ♗g7 24.♕g5 ♕f6 25.♕g4 c2 26.♗e2 ♖d4 27.f4 ♖d1+ 28.♗xd1 ♕d4+ 0-1.

You might also see a parallel with the self-restraint that Keres needed to exercise in the exceptionally fraught period after the end of the Second World War. With Estonia now under Soviet control after a period of annexation by Nazi Germany, Keres’s participation in tournaments in Nazi Germany was an exceptionally dangerous fact and indeed it seems only his potential usefulness as a chess player of the highest class kept him from being sent to a corrective labour camp. This tragic and murky period in Keres’s life is dealt with in great depth by Grents.

All four volumes are fantastic, but my biggest favourite is Volume 3 which is mainly dedicated to the annotations Keres made for his book 100 Selected Games covering the period 1931 to 1958. I’ve always had the impression that Keres’s annotations were a little colourless, far removed from Tal’s playfulness and fantasy or Botvinnik’s powerful, cutting judgements. However, reading them again, I’m simply staggered at the sheer amount of analytical work he must have spent on the book – on all phases of the game including some very complicated endgames – as well as in admiration of the balanced and instructive explanations. Of course, there are undoubtedly plenty of analytical mistakes to be discovered by our silicon friends – as I am about to start discovering – but the essential quality of the human judgements is indisputable.

To finish off, let me show you an absolutely bananas game, which Keres ended up losing in the 1936 Estonian Championship play-off against his erstwhile rival Paul Schmidt.

Paul Keres - Paul Felix Schmidt

Parnu match 1936 (2)

English Opening

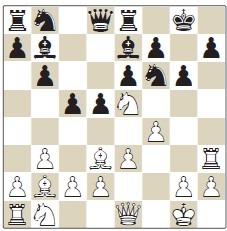

1.c4 ♘f6 2.♘c3 e5 3.f4 Some special Keres preparation for the match, with which he scored a princely 0/2!

Some special Keres preparation for the match, with which he scored a princely 0/2!

3...e4

3...exf4 is best of course but you can imagine Schmidt was keen to cross Keres’s intentions.

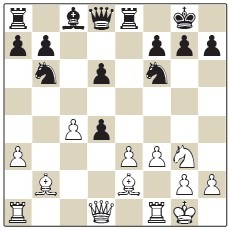

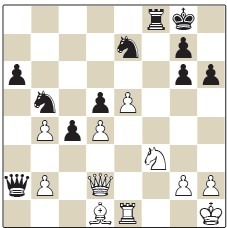

4.♕c2 d5 5.cxd5 ♗f5 6.♕b3 ♘bd7 7.♕xb7

This is really asking for it. The engines give Black as winning already!

7...♗c5 8.♕b3 0-0 9.e3 ♘b6 10.♘ge2 h5 11.♕b5 ♕e7 12.b4 It’s quite hard to predict any of White’s moves, but this move sets a delicious little trap into which Black falls. At least, I can’t imagine Black saw it, whatever Schmidt said in his annotations!

It’s quite hard to predict any of White’s moves, but this move sets a delicious little trap into which Black falls. At least, I can’t imagine Black saw it, whatever Schmidt said in his annotations!

12...♗xb4 13.d6

Wins a piece by hitting both the defender of the bishop on b4 and the bishop on f5.

13...♕xd6 14.♕xf5

White is completely winning but the opening has been so weird, Black still has some play against some of White’s weaknesses.

14...♘c4 15.a3 ♗xa3 16.♘b5 It’s as if Keres can’t simply play to consolidate his position: he just has to force some more crazy tactics!

It’s as if Keres can’t simply play to consolidate his position: he just has to force some more crazy tactics!

16...♗xc1 17.♘xd6 ♗xd2+ 18.♔d1 cxd6

It’s getting quite complicated now and after White’s next move, the engines consider that White only has a small edge despite being a queen for a knight up!

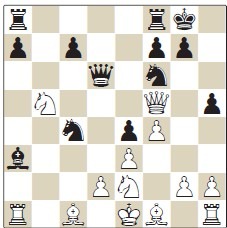

19.♕b5 ♘g4 20.♘g3

20.♕xc4 ♘xe3+ 21.♔xd2 ♘xc4+ was still a slight edge for White according to the engines. Now we are into 0.00 territory!

20...♘gxe3+ 21.♔e2 ♖ab8 22.♕a4 d5

It’s so hard for White to get his king out of this three-minor piece net and ...♖b2 is coming next! So White very naturally prevents it!

23.♖a2 ♗c3 Schmidt has played pretty flawlessly since the queen sacrifice and this move puts Black into a winning position. ...♖b1 is coming next and White’s position is ever more paralysed.

Schmidt has played pretty flawlessly since the queen sacrifice and this move puts Black into a winning position. ...♖b1 is coming next and White’s position is ever more paralysed.

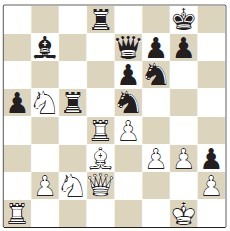

24.h3 ♖b1 25.♘xh5 ♖fb8

Calmly bringing all the pieces into play. The final attack is nearby.

26.♔f2 ♗e1+ 27.♔g1 ♘xf1 28.♖a1 Allowing a neat final mating pattern. Black to play and win!

Allowing a neat final mating pattern. Black to play and win!

28...♗f2+ 29.♔xf2 ♖8b2+ 30.♔g1 ♘fe3+ 0-1.

This set of four volumes is definitely one for every birthday or Christmas wish list. Fantastic games and a fascinating life story, beautifully produced! 5 stars!

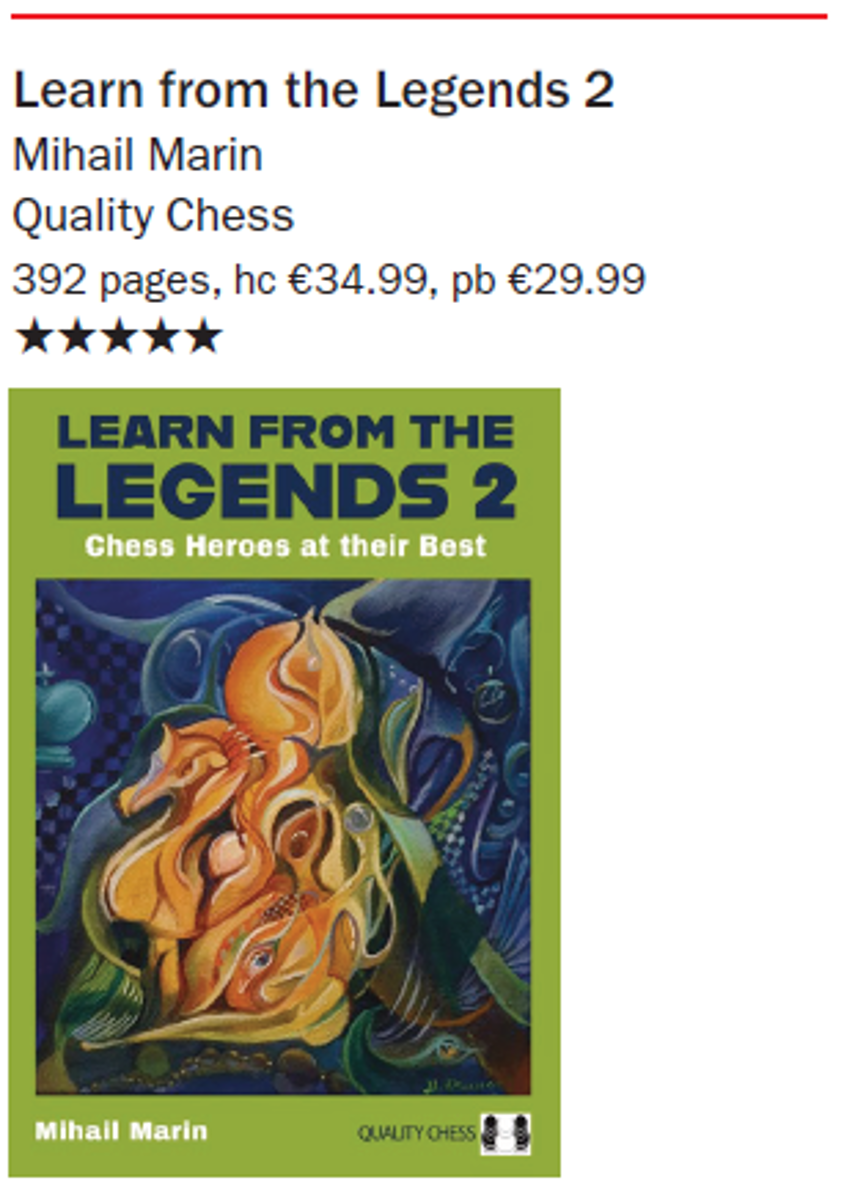

I’ve already mentioned Learn from the Legends 2, which is Mihail Marin’s second volume dedicated to aspects of the play of some of the great names of the past. This book focuses on five ‘nearly-men’: players who came close to the very top but never quite made the final step. We mentioned Paul Keres already, and Marin also looks at Leonid Stein, Lev Polugaevsky, David Bronstein and Lajos Portisch.

I’ve already mentioned Learn from the Legends 2, which is Mihail Marin’s second volume dedicated to aspects of the play of some of the great names of the past. This book focuses on five ‘nearly-men’: players who came close to the very top but never quite made the final step. We mentioned Paul Keres already, and Marin also looks at Leonid Stein, Lev Polugaevsky, David Bronstein and Lajos Portisch.

In contrast to Marin’s first volume, which dealt with a wide range of topics – ‘Karpov’s handling of bishops of opposite colour’ and ‘Tal’s handling of heavy pieces vs. minor pieces’ – this volume has a clear focus on the wilder side of the game as Marin explains: ‘I started my work free of preconceptions but, as the book progressed, it became clear that tactical abilities and attacking skills were common elements in the styles of my heroes. This discovery gave me the general direction for the book, turning it into a slightly unusual form of tactical and attacking manual, within a biographical framework.’

One very interesting name in the list is Portisch. He’s one of those players whose openings I know well but very few complete games! Marin acknowledges the surprise element but points out that Portisch qualified eight times for the Candidates – a record only surpassed by Korchnoi – and moreover ‘he was also one of the players I was rooting for during my teenage years, a period in which I had the opportunity to play three games against him – all ending in my defeat’.

As a professional, I had a very flat and superficial impression of Portisch – 2D rather than 3D you might say. I felt that he was a very strong player but not one who would surprise you. He would consistently win some powerful games with strong opening play, draw a lot too and lose a

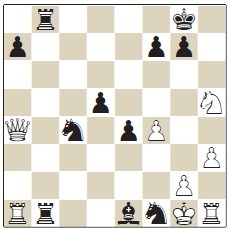

few to the very top. So I was only interested in stealing his openings but not really the rest of his play. Marin’s view is of course much more nuanced and it was a pleasure to discover all the other facets of his game. Let’s just add it to the list of things I’ve been blind about during my career! Perhaps, however, the section that had me smiling in astonishment the most was the one on Bronstein. He’s not one of my absolute favourite players, but had a strange and uncanny ability to – as Marin puts it – ‘mould the position the way he wanted and to undertake concrete actions dictated by his heart and understanding.’ This game against the super-strong Lev Aronin is a case in point. If you were looking at the game superficially, your attention might be drawn only to the spectacular position at move 32, where Black has two connected passed pawns for a sacrificed piece. But as Marin’s comments show, it’s the play before that which is really remarkable!

Perhaps, however, the section that had me smiling in astonishment the most was the one on Bronstein. He’s not one of my absolute favourite players, but had a strange and uncanny ability to – as Marin puts it – ‘mould the position the way he wanted and to undertake concrete actions dictated by his heart and understanding.’ This game against the super-strong Lev Aronin is a case in point. If you were looking at the game superficially, your attention might be drawn only to the spectacular position at move 32, where Black has two connected passed pawns for a sacrificed piece. But as Marin’s comments show, it’s the play before that which is really remarkable!

Lev Aronin - David Bronstein

Tartu 1962

Sicilian Defence, O’Kelly Variation

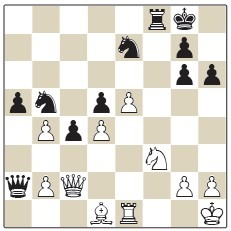

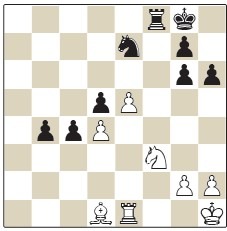

1.e4 c5 2.♘f3 a6 3.♗e2 d6 4.0-0 ♘f6 5.♘c3 e5 6.d3 ♗e7 7.♘d2 0-0 8.f4 exf4 9.♘f3 d5 10.♗xf4 ♘c6 11.e5 ♘e8 12.♔h1 ♘c7 13.♕d2 ♗f5 14.♖ae1 ♘e6 15.♗g3 ♗g6 16.♗d1 b5 17.♘e2 17...c4

17...c4

Marin focuses more on 16...b5 but this move certainly raised my eyebrows. Forcing White to consolidate his e5-pawn, thereby freeing his knight on f3 and bishop on g3 for action on the kingside seems exceptionally doubled-edged to me. Intuitively, I’d be thinking more about ...d4 than ...c4. Well ...d4 isn’t bad, but Bronstein’s move is the engine’s favourite!

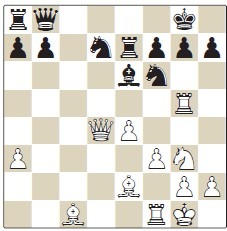

18.d4 b4 19.c3 ♕a5

Again the engine move – concrete and challenging. Bronstein has transformed the somewhat sleepy-looking position on the 16th move into a race on opposite wings!

20.♗h4 ♖ab8 21.♗xe7 ♘xe7 22.♘g5 ♘c7 Another remarkable move! Bronstein moves the knight out of the path of the exchange. My first thought after the initial shock was that this must be a little light-stepping with the knight, intending ...h6 and then a return to e6 after driving away the knight from g5.

Another remarkable move! Bronstein moves the knight out of the path of the exchange. My first thought after the initial shock was that this must be a little light-stepping with the knight, intending ...h6 and then a return to e6 after driving away the knight from g5.

23.♘f4 h6 24.♘xg6 fxg6 25.♖xf8+ ♖xf8 26.cxb4 ♕xa2 27.♘f3 ♘b5 The engine prefers 27...♘e6 but this is yet another amazing idea. Black has two ideas: ...c3 to force the exchange of queens followed by recapturing on c3, or the even more amazing ...♖xf3 followed by ...c3, when the queen on d2 is undefended and thus bxc3 is impossible. For that reason, Aronin protects his queen while eyeing Black’s kingside light squares.

The engine prefers 27...♘e6 but this is yet another amazing idea. Black has two ideas: ...c3 to force the exchange of queens followed by recapturing on c3, or the even more amazing ...♖xf3 followed by ...c3, when the queen on d2 is undefended and thus bxc3 is impossible. For that reason, Aronin protects his queen while eyeing Black’s kingside light squares.

28.♕c2 a5 Another move that shocks: why is Black getting rid of White’s weakest pawn? The answer is that after 29.bxa5 ♕xa5 Black has the dual threat of ...♘xd4 and ...♖xf3, overloading the knight on f3, which has to defend the d4-pawn and the rook on e1. After the virtually forced 30.♖g1 Black has follow-up ideas like 30...♘f5 or 30...♖f4. The engine is giving Black a decisive advantage. Such amazing vision from Bronstein!

Another move that shocks: why is Black getting rid of White’s weakest pawn? The answer is that after 29.bxa5 ♕xa5 Black has the dual threat of ...♘xd4 and ...♖xf3, overloading the knight on f3, which has to defend the d4-pawn and the rook on e1. After the virtually forced 30.♖g1 Black has follow-up ideas like 30...♘f5 or 30...♖f4. The engine is giving Black a decisive advantage. Such amazing vision from Bronstein!

29.♕a4

Aronin finds a tactical resource and this leads to the situation I mentioned earlier.

29...♕xb2 30.♕xb5 ♕xb4 31.♕xb4 axb4 The engines give Black a clear advantage. Marin points out that ‘after conducting a strategic or tactical phase brilliantly, Bronstein had a tendency to relax prematurely (or maybe he simply became tired) causing him to play less accurately in the technical phase’. Bronstein eventually brought home the point after 71 moves.

The engines give Black a clear advantage. Marin points out that ‘after conducting a strategic or tactical phase brilliantly, Bronstein had a tendency to relax prematurely (or maybe he simply became tired) causing him to play less accurately in the technical phase’. Bronstein eventually brought home the point after 71 moves.

One day I will give Marin fewer than five stars, but today is not that day! A really lovely book, that I read at a joyously furious pace! 5 stars!

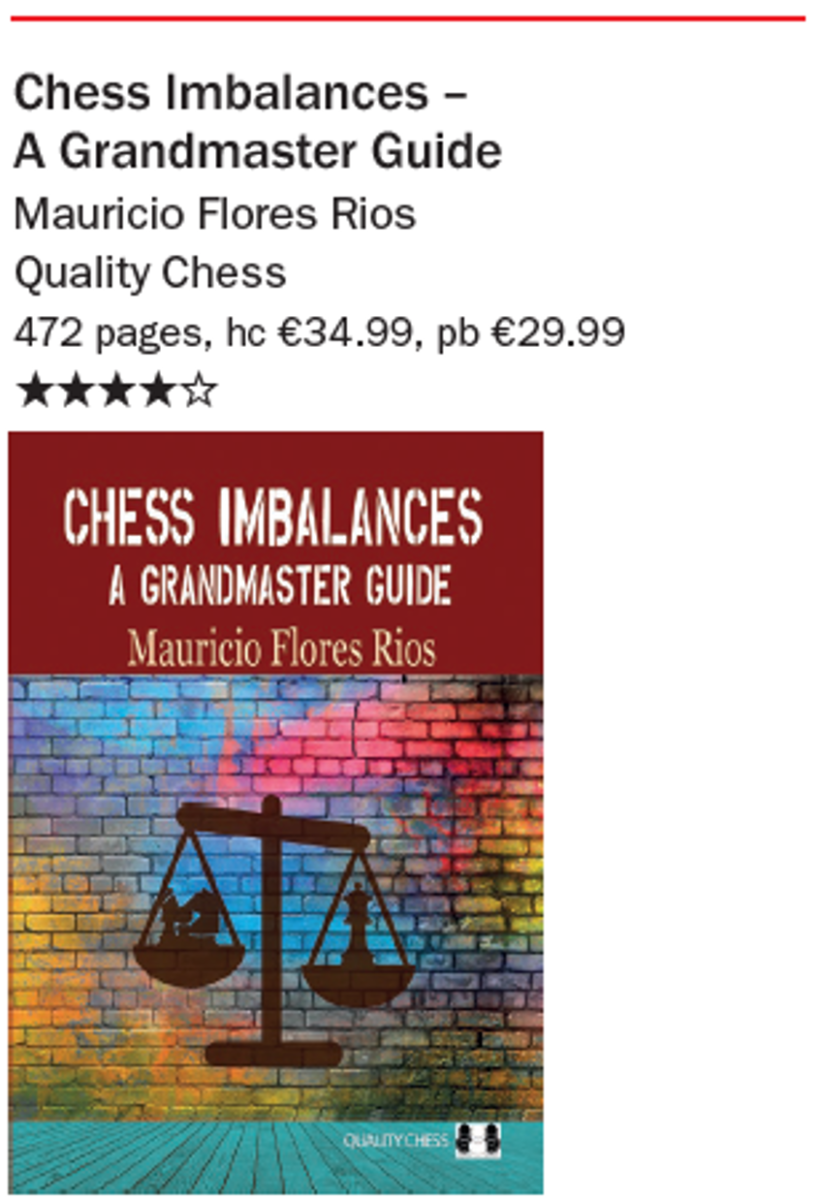

We finish this month’s reviews with Chess Imbalances: A Grandmaster Guide by Mauricio Flores Rios. Just three books this month, but I did read 4,000 pages on Keres you know!

We finish this month’s reviews with Chess Imbalances: A Grandmaster Guide by Mauricio Flores Rios. Just three books this month, but I did read 4,000 pages on Keres you know!

This impressive volume of 470 pages deals with imbalances in chess positions, starting with the smallest non-material imbalances (knight against bishop, rook against two minor pieces) before moving on to the more exciting material imbalances such as pawn sacrifices, exchange sacrifices, piece sacrifices and queen against anything. The last three chapters are a collection of shorter material that didn’t quite fit into the main chapters and a series of thirty puzzles with solutions.

‘Ooh material imbalances, that sounds complicated’, may be the first reaction when hearing the title... and indeed, yes, it is complicated! I suspect that I may have been suffering from a little bit of brain overload after reading so much Keres, but my head was definitely spinning while reading through Rios’s detailed analysis of some of these middlegame positions. That’s not to say that Rios doesn’t draw any general rules – readers (like me) who enjoyed his Chess Structures: A Grandmaster Guide will also find a good amount of high-level advice here too. But there is a vast amount of concrete analysis covering the middlegame and endgame stages of the game and at times it feels quite overwhelming. Reading through it made me wonder whether the book would maybe shine at its brightest in a digital format where it’s easier to hide and reveal variations depending on your mood.

I was very much torn while reading this work. On the one hand, I am quite in awe of the amount of effort the author has put into all manner of positions – opposite-coloured bishop middlegames without queens, rook against two knights in a sharp middlegame – which might normally only get a cursory glance if you saw the game in a database. For example, who would have thought that you could say so much and find so much interest in this position?

Diego Flores - Husein Aziz Nezad

Tromsø Olympiad 2014 My mouth is opening into a yawn as I see it, but Rios does a wonderful job of highlighting the challenges Black faces after the strong move 26.e5!.

My mouth is opening into a yawn as I see it, but Rios does a wonderful job of highlighting the challenges Black faces after the strong move 26.e5!.

On the other hand, reading through the book felt quite heavy at times. I had a think about why that might be and I decided that it’s somewhat inherent to analysing human games in such exacting detail. The number of mistakes is quite high, which means that the evaluation of a position swings from move to move, even though the moves of both players seem very reasonable. So the games can get a little hard to follow: it’s hard to keep your train of thought while reading and to emerge with a clear summary for yourself at the end. But if I ever developed an interest in a type of unbalanced position, this would be the first book I’d dive into to see if any of Rios’s insights could help me make sense of my experience.

So more of a workbook than a pleasant casual read... but perhaps the title ‘A Grandmaster Guide’ suggested that in any case!’ Really impressive in many ways: 4 stars! ■