Seekers of the ultimate truth

These book reviews by Matthew Sadler were published in New In Chess magazine 2025#3

To players of my generation, the clash between Nimzowitsch and Tarrasch is still a burning issue! You truly feel some personal connection because you read Nimzowitsch’s My System as an impressionable teenager. Willy Hendriks chronicles the clash in his new book, full of humour and larger-than-life characters.

At such times, a certain gloom (British understatement) about the life that awaits us is unavoidable, but chess books remain a ray of joy. In particular, I’ve loved the attention that authors of the past years have shown to the many facets of chess history. The publishing house Elk and Ruby has brought the grimly fascinating Soviet era of chess to life, highlighting the lives and games of many forgotten figures of that period, while, thanks to books about FIDE President Folke Rogard and Gideon Stahlberg, I seem to have spent many days reading about the Swedish chess scene from the 1920s onwards! Willy Hendriks’s focus in his books is the philosophical battles of chess lore. Because in the old days, it wasn’t just about who was the strongest; it was just as important who was right! A player like Steinitz not only had to prove he was the strongest player, he needed a chess credo to match, thus demonstrating not only his practical but also intellectual superiority over his opponents. Hendriks’s superb The Ink War chronicled the struggle for supremacy both on- and off-the-board between Steinitz and Zukertort (most keenly felt by Steinitz). His latest work The Philosopher and the Housewife does the same for Nimzowitsch (the ‘philosopher,’ of course) and Tarrasch (designated as the ‘housewife’ by Nimzowitsch). Moving past the misogyny of the insult, the essence of Nimzowitsch’s characterisation was that Tarrasch’s advice was nothing more than practical, homespun wisdom and only of use to beginners, whereas Nimzowitsch’s deep and profound conception of chess was of far greater intellectual value. Amusingly, too, Hendriks brings in a third voice – the Russian player Semyon Alapin – who argued rather powerfully that both Nimzowitsch and Tarrasch were wrong!

Willy Hendriks’s focus in his books is the philosophical battles of chess lore. Because in the old days, it wasn’t just about who was the strongest; it was just as important who was right! A player like Steinitz not only had to prove he was the strongest player, he needed a chess credo to match, thus demonstrating not only his practical but also intellectual superiority over his opponents. Hendriks’s superb The Ink War chronicled the struggle for supremacy both on- and off-the-board between Steinitz and Zukertort (most keenly felt by Steinitz). His latest work The Philosopher and the Housewife does the same for Nimzowitsch (the ‘philosopher,’ of course) and Tarrasch (designated as the ‘housewife’ by Nimzowitsch). Moving past the misogyny of the insult, the essence of Nimzowitsch’s characterisation was that Tarrasch’s advice was nothing more than practical, homespun wisdom and only of use to beginners, whereas Nimzowitsch’s deep and profound conception of chess was of far greater intellectual value. Amusingly, too, Hendriks brings in a third voice – the Russian player Semyon Alapin – who argued rather powerfully that both Nimzowitsch and Tarrasch were wrong!

I’m wondering whether the younger reader might read this description, raise their eyes to the ceiling, and mutter ‘What does it all matter?’ But to players of my generation, the clash between Nimzowitsch and Tarrasch is still a burning issue! You truly feel some personal connection, because you read Nimzowitsch’s My System as an impressionable teenager, curled your lip in disdain at the descriptions (repeated in every book you read) of Tarrasch’s talentless dogmatism, and cheered at Lasker’s crushing victory over prejudice and short-sightedness! As you grew older, you maybe got a little more sceptical (British understatement again) of Nimzowitsch’s writings, but you still maintained your belief that he was on the ‘right side’ of progress, as opposed to Tarrasch, who was reactionary and conservative. Which, I suppose, is as good an illustration as any of why winning the ‘intellectual’ war is as important as winning the chess one! It’s also a good illustration of why it’s important to revisit the past as Hendriks does and consider dispassionately how matters actually stood. Hendriks starts the book with brilliant quotes from each protagonist who set the scene beautifully. They are a little wordy, but the high-flying language captures the ambitions of both men very well.

Hendriks starts the book with brilliant quotes from each protagonist who set the scene beautifully. They are a little wordy, but the high-flying language captures the ambitions of both men very well.

First Tarrasch: ‘I do not limit myself to the game at hand, but search for the stable point in the flight of the appearances, most often I abstract from the specific case towards the general, and I set up a number of principles and doctrines, whose knowledge will improve the level of play enormously’.

And now, Nimzowitsch: ‘But in the quiet lived and searched someone who loved the truth in chess and, in a tough fight, endeavoured to discern its everlasting laws. And that person – was me. And what I was lucky enough to find were strictly formulated laws of chess strategy expanded into a harmonious whole’.

Both believed that chess was governed by ‘hidden laws’ and that they could discover them and capture them in language to share them with others. But certainly, Nimzowitsch believed that only he possessed the true knowledge and despised Tarrasch because ‘all his views, his sympathies and antipathies, and above all his inability to conceive any new idea – all that obviously proved the mediocrity of his personality’.

This conflict between two antagonistic seekers of the ultimate truth of chess over a period of almost thirty years would be interesting enough, but the addition of Alapin into the mix adds another fascinating layer. The presciently modern Alapin was dismissive of the use of language to capture the essence of chess: ‘The most important difficulty here, in my opinion, is the far too great power of “words” on our mind, which, captivated by the enchanting sound of an easily grasped, elegant and fascinating dialectic, almost always allows itself to be carried away into overestimating the practical value of general considerations.’ Alapin wanted writers not to weave stories but to justify their ideas with variations! Nimzowitsch’s reaction is quite hilarious: ‘And now comes something facetious. One fine day someone comes up to me with the attempt to refute!!! My laws – by variations!!!’ (The exclamation marks are not mine, by the way, though they could be!)

It’s strange, funny, and thought-provoking to follow this battle with Hendriks through the many tournament games that Tarrasch and Nimzowitsch disputed (somewhat in Nimzowitsch’s favour, although Tarrasch was past his peak when Nimzowitsch became strong) and countless polemics! The culmination of the book is a very nice chapter entitled ‘Artist of Variations’ – Nimzowitsch’s dismissal of Alapin – in which Hendriks brings together the salient points from all these years of disagreement, and adds a modern and personal perspective (‘Move first, think later!’)

Having enjoyed Hendriks’ previous books, I was looking forward enormously to reading this one, and I certainly wasn’t disappointed. It’s full of humour, surprises, good chess – some familiar, some not – and larger-than-life characters! 5 stars! Obviously, the combination of this book with Dutch IM Nick Maatman’s The Hidden Laws of Chess was irresistible! There have been two volumes so far: Volume 1: Mastering Pawn Structures and Volume 2: Mastering Dynamics. So, what is a ‘Hidden Law’? According to the author, ‘On a surface level, there are Laws that comprise the comparative value of the pieces. On a deeper level, there are Hidden Laws that encompass elements such as the importance of space, the quality of a pawn structure, the strength or weakness of an isolated pawn, the importance of a key square etc... How do these Hidden Laws compare to chess wisdom that has been captured in chess literature? To a certain extent, there is overlap, but the Hidden Laws of Chess are recognizable when three features are present: they operate in a lawlike manner, they operate under the surface, they are context-dependent’. The first book has chapters covering factors such as a space advantage, doubled pawns, backwards pawns, isolated pawns, and hanging pawns. Each chapter starts with a set of preview exercises (which are answered in the chapter itself, a neat idea) and ends with a quiz of twelve positions, with the solutions at the end.

Obviously, the combination of this book with Dutch IM Nick Maatman’s The Hidden Laws of Chess was irresistible! There have been two volumes so far: Volume 1: Mastering Pawn Structures and Volume 2: Mastering Dynamics. So, what is a ‘Hidden Law’? According to the author, ‘On a surface level, there are Laws that comprise the comparative value of the pieces. On a deeper level, there are Hidden Laws that encompass elements such as the importance of space, the quality of a pawn structure, the strength or weakness of an isolated pawn, the importance of a key square etc... How do these Hidden Laws compare to chess wisdom that has been captured in chess literature? To a certain extent, there is overlap, but the Hidden Laws of Chess are recognizable when three features are present: they operate in a lawlike manner, they operate under the surface, they are context-dependent’. The first book has chapters covering factors such as a space advantage, doubled pawns, backwards pawns, isolated pawns, and hanging pawns. Each chapter starts with a set of preview exercises (which are answered in the chapter itself, a neat idea) and ends with a quiz of twelve positions, with the solutions at the end.

I read Volume 1 some time ago, and looking back on my notes, it seemed to unleash the cantankerous old man lurking within me (or maybe it’s just how I am nowadays). There were plenty of examples I liked, but I couldn’t get past the idea of how very strange it was to talk about Hidden Laws when you’re staring at a pawn structure that already tells you a lot about itself just from the way it looks! Quite apart from the fairly extensive literature already available on these subjects. I’d mention in particular Chess Structures – A Grandmaster Guide by Mauricio Flores Rios for Quality Chess. I was less grumpy about Volume 2, as I guess the idea of Hidden Laws of Dynamics (which are of course, much harder to ‘see’ in a position) appealed to me a little more. I still felt a disconnect between my expectation of Laws (Hidden or not) and the content of the book, which has chapters on ‘Calculation’, ‘Judgment’, ‘Sacrifices’, ‘g2-g4’, and ‘h2-h4’. The book read to me like a mixture of tips for practical play and some rather specific chess ideas. So, I’ve ended up in the odd position of quite enjoying a lot of the examples in the books but still writing about them with a sour expression on my face!

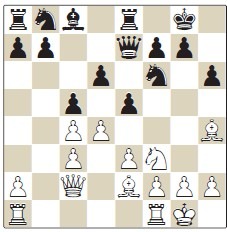

Let me switch to the positive and show you a brief excerpt from one of the passages that I liked from the Volume 1 chapter on doubled pawns. I knew the game, of course, but my attention had always been drawn to the later parts of the game. Maatman also correctly devoted time to the opening struggle, which was more sophisticated than I had realised.

Mikhail Botvinnik

Vitaly Chekhover

Leningrad ch-USSR 1938

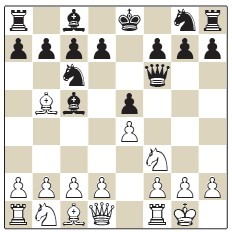

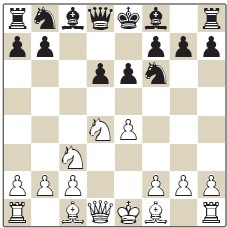

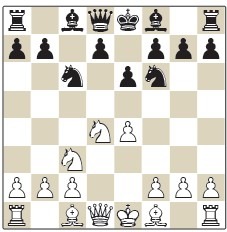

1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 e6 3.♘c3 ♗b4 4.♘f3 0-0 5.♗g5 d6 6.e3 ♕e7 7.♗e2 e5 8.♕c2 ♖e8 9.0-0 ♗xc3 10.bxc3 h6 11.♗h4 c5 12.♖ae1

12.♖ae1

‘Botvinnik is preparing ♘d2, after which he intends to increase the pressure on the black centre by playing f2-f4. A rook is required on e1 before this plan can be carried out. The immediate 12.♘d2? would fail to 12...exd4! as the bishop on e2 is left unprotected.’

12...♗g4

‘Chekhover finds the only move that stops Botvinnik’s plan. After the intended 13.♘d2, he will play 13...♗xe2 14.♖xe2 exd4. With an unprotected rook on e2, White cannot take back twice.’

13.♗xf6

‘White gives up the bishop pair voluntarily so he can make use of a small tactic.’

13...♕xf6 14.♕e4

‘The mark of excellent players is that they put their opponents into positions where they can make mistakes. Here, Chekhover has a difficult choice to make. He must simultaneously defend b7 and solve the problem of the bishop on g4.’

14...♗xf3

‘A slight inaccuracy allows Botvinnik to execute his plan. Retreating the bishop with 14...♗c8 was more tenacious though White might still be able to fight for an advantage with the aforementioned plan of 15.♘d2 followed by f2-f4.’

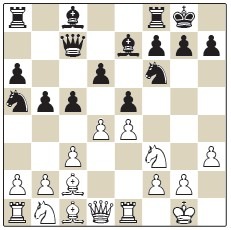

15.♗xf3 ♘c6 ‘Botvinnik must have accounted for the knight move. Now his plan of advancing with f2-f4 is completely off the table. What did he have in mind here?’

‘Botvinnik must have accounted for the knight move. Now his plan of advancing with f2-f4 is completely off the table. What did he have in mind here?’

16.dxc5

‘After the elimination of the light-squared bishop, Black has no good way to guard the d5-square. The doubled pawns act as pillars to support a complete command over the central squares. It is true that Botvinnik will have more pawn islands and isolated doubled pawns on the c-file, something which is generally frowned upon. But here it is not problematic. White will occupy the d5-square with a rook and an exchange on d5 will grant White the opportunity to repair his structure with cxd5.’

16...dxc5 17.♖d1 ♖ad8 18.♖d5 b6 19.♖fd1 ♘a5 20.h3 ♖xd5 21.♖xd5 ♕e7 22.♗g4 ♕b7 23.♗f5 ♕b8 24.♖d7 ♖d8 25.♕xe5 ♘xc4 26.♕xb8 ♖xb8 27.♗e4 ♘a3 28.♗d5 ♖f8 29.e4 a5 30.c4 b5 31.cxb5 ♘xb5 32.e5 a4 33.f4 ♘d4 34.♔f2 g5 35.g3 gxf4 36.gxf4 ♘e6 37.♔e3 c4 38.f5 ♘c5 39.♖c7 ♘d3 40.e6 fxe6 41.fxe6 1-0.

The subtlety of this opening phase had completely passed me by despite seeing the game multiple times over the years, so I was grateful to Maatman’s insightful comments for showing me something fresh in an old game!

In summary, I don’t think the books live up to their rather ambitious titles, but the content is instructive, pleasantly written, and easy to follow, so I think we’ll centralise on 3 stars! Capablanca’s Endgame Technique is another lovely Chessable crossover, a hardback book with a clear typeface and colour diagrams. In this short book of 119 pages, Alex Colovic takes us on a tour of excerpts from twelve Capablanca endgames, often discussing the crucial phase of transition into the endgame: an area in which Capablanca was particularly skilful.

Capablanca’s Endgame Technique is another lovely Chessable crossover, a hardback book with a clear typeface and colour diagrams. In this short book of 119 pages, Alex Colovic takes us on a tour of excerpts from twelve Capablanca endgames, often discussing the crucial phase of transition into the endgame: an area in which Capablanca was particularly skilful.

All of the games in the book are well-known, which worried me a little when I skimmed through it: how much more is there to say about these famous Capablanca endgames? Well, I was completely won over by Colovic’s treatment of the material, which both sheds fresh light on many details of the games themselves while also acting as inspiration for the treatment of your own endgames.

One funny moment came when I nodded my head and said, ‘The guy’s not wrong, you know!’ It happened when Colovic discusses a period of repetition in the famous Capablanca-Ragozin game.

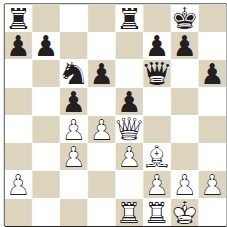

Jose Raul Capablanca

Viacheslav Ragozin

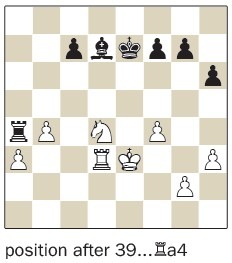

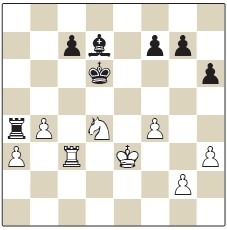

Moscow 1936 Here Capablanca repeated moves a few times with: 40.♖c3 ♔d6 41.♖d3 ♔e7 42.♖c3 ♔d6

Here Capablanca repeated moves a few times with: 40.♖c3 ♔d6 41.♖d3 ♔e7 42.♖c3 ♔d6 Colovic’s discussion of this moment is excellent and original:

Colovic’s discussion of this moment is excellent and original:

‘A repetition of moves which is usually used to reach the time control or to gain 30 seconds on the clock in modern times. However, there is a psychological aspect when it comes to the repetition of moves in superior positions. In Soviet literature, it was lauded as good practice when converting an advantage, but in my own practice, I realized that things are not as straightforward as they may appear at first sight. Further deliberations on the subject led me to realise that there are two types of players. Players like Capablanca and Karpov (for example) enjoyed repeating moves. It gave them a sense of superiority, as if they were playing cat and mouse with their opponent. They feel comfortable repeating moves and were doing so whenever possible.

Other players (like yours truly) feel very uncomfortable repeating moves. The repetition feels like a sign of indecisiveness, of not knowing what to do next. It also feels like giving the opponent quick and free moves (since in an inferior position the opponent is not against a draw so they will repeat quickly). I became aware that the repetition of moves often would break my usual playing rhythm of going forward and would confuse me. So once I understood all of the above, I stopped repeating moves unless I badly needed to gain time on the clock. Another thing I noted was that players with straightforward and forceful technique (like Fischer) never repeated moves and were very direct when converting an advantage without making superfluous moves. There is no right and wrong when it comes to repetition of moves in such situations. What is important, however, is to understand in which category of players you fall so that you can take the approach that is most comfortable to you personally.’

I wish I’d had that advice during my playing career after years of unhappily sweating over repetitions! I always felt I should demonstrate my grandmasterly strength, but only succeeded in making myself nervous! It’s just one example of how Colovic turns these excellent technical games of Capablanca into a valuable learning experience.

I hesitated about whether to give this book the full 5 stars; in the end, I decided that the book was perhaps a little on the short side for the full monty, but it’s still a richly deserved 4 stars! Recommended!

By the way, in his introduction, Colovic mentions the San Sebastian tournament of 1911, which was Capablanca’s first elite tournament victory at the age of 23, scoring 9½/14, ahead of Rubinstein, Vidmar, Marshall, and Nimzowitsch. A hardback English version of the tournament book San Sebastian 1911 by the American correspondence player Robert Irons (Russell Enterprises) is now available. I won’t review it, because I wasn’t completely happy with the annotations, but it was good to finally see a version in a language I can understand! From the lofty heights of chess philosophy and artistry in the 1920s to the nitty-gritty of modern opening preparation! The Greek theoretical expert and correspondence player Nikolaos Ntirlis has taken aim at Black players again, this time with the king’s pawn, with his latest work Reimagining 1.e4 (Quality Chess). ‘Cunning, Crafty and Concise’ is the subtitle, and indeed, a whole 1.e4 repertoire in 300 pages of reasonably large print is pretty impressive! 1.e4 e5 gets about 120 pages, the Sicilian gets 100 pages, the French just over 20 pages, the Caro-Kann just over 10 pages, and the rest (Scandinavian, Modern, Alekhine, etc.) almost 30 pages. Reading through it the first time at speed, fuelled by wine and biscuits, I suddenly realised I’d already zoomed past the 1.e4 e5 section and was now in hand-to-hand combat with the Sicilian. I truly wondered whether I’d skipped some pages by mistake!

From the lofty heights of chess philosophy and artistry in the 1920s to the nitty-gritty of modern opening preparation! The Greek theoretical expert and correspondence player Nikolaos Ntirlis has taken aim at Black players again, this time with the king’s pawn, with his latest work Reimagining 1.e4 (Quality Chess). ‘Cunning, Crafty and Concise’ is the subtitle, and indeed, a whole 1.e4 repertoire in 300 pages of reasonably large print is pretty impressive! 1.e4 e5 gets about 120 pages, the Sicilian gets 100 pages, the French just over 20 pages, the Caro-Kann just over 10 pages, and the rest (Scandinavian, Modern, Alekhine, etc.) almost 30 pages. Reading through it the first time at speed, fuelled by wine and biscuits, I suddenly realised I’d already zoomed past the 1.e4 e5 section and was now in hand-to-hand combat with the Sicilian. I truly wondered whether I’d skipped some pages by mistake!

It’s an excellent repertoire based on what I’d characterise as really serious lines. Not a Closed Sicilian or a cowardly 3.♗b5+ to avoid the Najdorf in sight! Ntirlis focuses on main lines,dotting them with fresh ideas, some new, some cutting edge, and some old but refreshed! I had a little think trying to work out what Ntirlis hadn’t covered to stay within this number of pages and I can reveal the shocking news that if you were to meet the Italian grandmaster star of the 1970s, Sergio Mariotti, across the board, you would not be ready to face him with this book, as his favourite idea 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗b5 ♗c5 4.0-0 ♕f6 is not covered! As far as I can judge, though, it’s only such lines at the periphery of playable (or just beyond!) that might escape the book’s attention.

As far as I can judge, though, it’s only such lines at the periphery of playable (or just beyond!) that might escape the book’s attention.

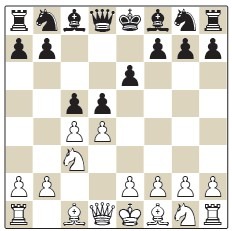

What I really liked about the book was the flexibility in the teaching approach. For example, in the main line Ruy Lopez with 11...♕c7.

1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗b5 a6 4.♗a4 ♘f6 5.0-0 ♗e7 6.♖e1 b5 7.♗b3 d6 8.c3 0-0 9.h3 ♘a5 10.♗c2 c5 11.d4 ♕c7 Ntirlis follows the engines and recommends 12.d5, closing the centre immediately. Obviously, in this case, concrete lines should take a back seat and inspiration through model games is required to demonstrate to the reader the potential of this approach. And that is what Ntirlis delivers in about five pages including a marvellous Stockfish demolition of Komodo and an equally vicious demolition of Shirov by Topalov!

Ntirlis follows the engines and recommends 12.d5, closing the centre immediately. Obviously, in this case, concrete lines should take a back seat and inspiration through model games is required to demonstrate to the reader the potential of this approach. And that is what Ntirlis delivers in about five pages including a marvellous Stockfish demolition of Komodo and an equally vicious demolition of Shirov by Topalov!

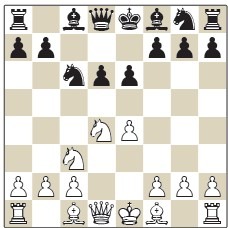

At the same time, when analysing the Sicilian Scheveningen, Ntirlis dedicates plenty of room to discussing specific early move orders, for example, not only the main line

1.e4 c5 2.♘f3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.♘xd4 ♘f6 5.♘c3 e6, but also the Taimanov move order 2...e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.♘xd4 ♘c6 5.♘c3 d6,

but also the Taimanov move order 2...e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.♘xd4 ♘c6 5.♘c3 d6, and even the more exotic Kan move order 2...e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.♘xd4 a6 5.♘c3 d6.

and even the more exotic Kan move order 2...e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.♘xd4 a6 5.♘c3 d6. With the vast amount of knowledge out there on every opening, it’s very difficult to find the right balance in such a repertoire book. Provide too much detail, and your readers become distressed before the game, straining to remember it all; provide too little, and your readers panic during the game, as the stress of playing triggers all sorts of worries that the book has not addressed. The more I read it, the more this book felt like a very good distillation of what a reasonably strong player would need to know to venture this whole repertoire with confidence. It’s a really impressive opening book once again from this author and gets a well-deserved 5 stars from me!

With the vast amount of knowledge out there on every opening, it’s very difficult to find the right balance in such a repertoire book. Provide too much detail, and your readers become distressed before the game, straining to remember it all; provide too little, and your readers panic during the game, as the stress of playing triggers all sorts of worries that the book has not addressed. The more I read it, the more this book felt like a very good distillation of what a reasonably strong player would need to know to venture this whole repertoire with confidence. It’s a really impressive opening book once again from this author and gets a well-deserved 5 stars from me! And finally, from a repertoire book for stronger players to a repertoire book aimed at beginners and improvers with a rating up to around 1200 (or a bit higher). Christof Sielecki’s My First Opening Repertoire brings together material from his popular and successful Chessable ‘My First Repertoire’ series for White and Black. In about 260 pages, the author gives a complete set of openings for both colours, including a 40-page section of model games – again, concision like this is no mean feat!

And finally, from a repertoire book for stronger players to a repertoire book aimed at beginners and improvers with a rating up to around 1200 (or a bit higher). Christof Sielecki’s My First Opening Repertoire brings together material from his popular and successful Chessable ‘My First Repertoire’ series for White and Black. In about 260 pages, the author gives a complete set of openings for both colours, including a 40-page section of model games – again, concision like this is no mean feat!

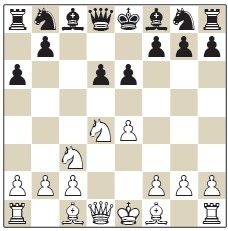

I’m not the ideal person to review a book aimed at beginners, not only because of my chess strength but also because of my age – my beginner days are really very hazy in my mind now! What I can definitely appreciate, however, is the rigour and discipline with which Sielecki presents the opening material, with no more than ten moves of depth (mostly a little less). I’d have said that it was impossible, but reading through the book, I rarely came across any line where I felt that a line was cut short prematurely. Essentially, Sielecki has chosen his lines carefully to make this whole approach work well, and I guess that a lot of unseen work went into achieving this. I confess that I was quite surprised by Sielecki’s choices for his Black repertoire of the Sicilian Four Knights

against 1.e4: 1.e4 c5 2.♘f3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.♘xd4 ♘f6 5.♘c3 ♘c6. And the Tarrasch against 1.d4: 1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.♘c3 c5.

And the Tarrasch against 1.d4: 1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.♘c3 c5. My instinct would always be to try to protect beginners against possible weak square complexes or static weaknesses like isolated pawns, but on reflection, I decided I liked Sielecki’s choice. The repertoire guarantees rapid development and active play for Black, and I think that at the beginner level (or improving beginner level), it’s very much worth challenging the White player in this way. I also liked the way Sielecki gives due attention to moves like 1.e4 c5 2.♗c4 and 1.e4 c5 2.d4 cxd4 3.♕xd4, which you see played a lot in the 1300-1400 Elo range on a site like chess.com. I think I may pick up a copy for my eldest nephew, who has started playing chess online and is currently disgracing the family name by starting his black games with 1...a5 and 2...♖a6! A very good effort – 4 stars! ■

My instinct would always be to try to protect beginners against possible weak square complexes or static weaknesses like isolated pawns, but on reflection, I decided I liked Sielecki’s choice. The repertoire guarantees rapid development and active play for Black, and I think that at the beginner level (or improving beginner level), it’s very much worth challenging the White player in this way. I also liked the way Sielecki gives due attention to moves like 1.e4 c5 2.♗c4 and 1.e4 c5 2.d4 cxd4 3.♕xd4, which you see played a lot in the 1300-1400 Elo range on a site like chess.com. I think I may pick up a copy for my eldest nephew, who has started playing chess online and is currently disgracing the family name by starting his black games with 1...a5 and 2...♖a6! A very good effort – 4 stars! ■