100 Studies and 50 Mistakes

These book reviews by Matthew Sadler were published in New In Chess magazine 2025#2

In idle moments, I’ve sometimes found myself thinking to which period of chess history I would choose to return if given access to a time machine (well it beats thinking about work I guess!). My choice has fallen most often on the period between the two World Wars. Pretty much everything you could love about chess is in there: fantastic players (Capablanca, Alekhine, Lasker, and a host of other colourful and interesting characters), huge classical tournaments, the emergence of new chess approaches such as hyper-modernism, a growing professionalism in opening preparation leading to new systems and discoveries, but not so much that lifelong King’s Gambit romantics like Rudolf Spielmann couldn’t find a place in the world elite.

However, chess history isn’t even a fraction of the whole story of course and chess players weren’t spared from the horrors of the rise of Nazism and the outbreak of war (the abovementioned Spielmann being one of many tragic stories). I had gained some knowledge about chess activity in Nazi Germany in the years leading up to and during the war, from the wonderful biography of the fine German player Kurt Richter by Alan McGowan (also published by McFarland). However, the purpose and organisation behind the Nazi government’s takeover of chess in those years hadn’t broken through into my consciousness.

Another fine 284-page book from McFarland, Chess in the Third Reich: How the Game Was Played, Glorified, and Abused in Nazi Germany 1933-1945 by Taylor Kingston, fills this gap and offers fascinating, sobering, and frightening reading – especially in the context of modern affairs, both chess-related and political.

Another fine 284-page book from McFarland, Chess in the Third Reich: How the Game Was Played, Glorified, and Abused in Nazi Germany 1933-1945 by Taylor Kingston, fills this gap and offers fascinating, sobering, and frightening reading – especially in the context of modern affairs, both chess-related and political.

The first three chapters of the book describe the illustrious context of German chess, starting from the mid-19th century until the earlier years of the Nazi regime from 1933-1935. Thereafter, each year until the end of the war is dedicated own chapter. Each chapter is sprinkled liberally with lightly annotated illustrative games of German players, some famous, some virtually unknown. Before reading the book, it had not occurred to me that the Nazi government might have had any particular interest in chess. I assumed that chess players and administrators would have been subject to the same discrimination and restrictions as other Germans and Austrians, but why would anyone put any effort into Nazifying something as unimportant as chess when you are intent on conquering the world?

It was part of the greater process of ‘synchronisation’ – a systematic effort by the Nazi government to enforce centralisation and conformity in every area of life – and chess was also a part of this. To this end, the existing German Chess Federation (DSB) was replaced seemingly overnight by the Greater German Chess Federation (GSB) run by a Nazi ideology. Quite disturbingly, the GSB had been set up on paper already in 1931, before the Nazis came to power, indicating that it was part of a pre-conceived strategy to substitute existing organisations with Nazi ones, once power was attained.

One of the goals of the GSB became to unearth pure ‘German’ talent since Germany’s strongest active player Efim Bogolyubov clearly did not fit the bill at all as he was a naturalised Ukrainian who had married and settled in Germany after being interned in Mannheim during the First World War along with several Russian chess players. This became particularly urgent with the 1936 Berlin Olympiad approaching, where anything less than an overwhelming victory by the – very much middle-ranking – German team would be seen as a failure.

Some factors contributed to improving German’s prospects: the clash with the great Nottingham 1936 tournament, which kept many top players away (including Bogolyubov), the reluctance of many Jewish players to play in Germany, and the expansion of teams to eight players with two reserves, benefiting Germany’s relative surfeit of second-rank players compared to other rivals. Finally, the absence of several strong teams like the United States made it more likely for the German team to play a leading role.

In the end, the Germans came third, behind Hungary and Poland for which Najdorf played a starring role, winning a gold medal on board two. A small passage from Najdorf about that is quite poignant: ‘On that day the Germans had to play the Polish anthem, and one of their officials called out “Moshe Mendel Najdorf, gold medal, first prize”. It was presented to me by Hans Frank; three years later he would be Governor of Poland and responsible for the extermination of my family.’

Perhaps the most incredible thing to me is that as Germany gained territory – first Austria and then particularly Poland – the same effort was put into assimilating the (non-Jewish) chess players and expanding the administrative influence of the GSB into these occupied territories. The terrible Governor of Poland, Hans Frank, was a chess enthusiast and had a vision of a pan-European chess federation with his city Krakow as its centre. Even in 1944, when everything was starting to fall apart, Frank was still organising chess tournaments around Krakow. After the war, Frank was sentenced to death at the Nuremberg tribunal for crimes against humanity.

With the subject matter, it’s difficult to say that I enjoyed the book, but I was fascinated by it and couldn’t stop thinking about it for days after. It brings home very strongly how dictatorships shape their citizens and how every pastime – however irrelevant in the grand scheme of things – can be a target for a dictatorship if it involves organised activity which needs to be controlled, or provides the possibility of glory (or humiliation). A really good book – 5 stars.

With the subject matter, it’s difficult to say that I enjoyed the book, but I was fascinated by it and couldn’t stop thinking about it for days after. It brings home very strongly how dictatorships shape their citizens and how every pastime – however irrelevant in the grand scheme of things – can be a target for a dictatorship if it involves organised activity which needs to be controlled, or provides the possibility of glory (or humiliation). A really good book – 5 stars.

We stay with chess history, but a slightly earlier period, with A Century of Chess, Book I: 1900-1909 by Sam Kahn (CarstenChess). This 286-page book is based on author Sam Kahn’s historical articles for chess.com and goes through the decade between 1900 and 1910 year-by-year, introducing the colourful players of that period and describing the most important matches and tournaments with annotated games by Cyrus Lakdawala and Carsten Hansen.

We stay with chess history, but a slightly earlier period, with A Century of Chess, Book I: 1900-1909 by Sam Kahn (CarstenChess). This 286-page book is based on author Sam Kahn’s historical articles for chess.com and goes through the decade between 1900 and 1910 year-by-year, introducing the colourful players of that period and describing the most important matches and tournaments with annotated games by Cyrus Lakdawala and Carsten Hansen.  I’m always happy to read something about chess in the first half of the 20th century and there were definitely a few things in the book that had me nodding in approval, most particularly a rather more generous appraisal of the great Polish player Dawid Janowsky (1868-1927) – just like Efim Bogolyubov mentioned above, one of my favourite grossly underrated players – than you normally see in chess history! I truly believe that he was right at the top of the chess world in the first half of the 1900s and he has played a large number of exceptionally interesting games. (I have published a series of 28 videos about his games and could have done many more).

I’m always happy to read something about chess in the first half of the 20th century and there were definitely a few things in the book that had me nodding in approval, most particularly a rather more generous appraisal of the great Polish player Dawid Janowsky (1868-1927) – just like Efim Bogolyubov mentioned above, one of my favourite grossly underrated players – than you normally see in chess history! I truly believe that he was right at the top of the chess world in the first half of the 1900s and he has played a large number of exceptionally interesting games. (I have published a series of 28 videos about his games and could have done many more).

Another favourite of mine – Richard Teichmann (1868-1925) – gets a slightly less sympathetic treatment, but you can’t have everything! I was slightly torn about the game selections and the annotations. Some of the more famous games have been previously annotated by many authors (including me!) and although it’s impossible to encompass all the sources, I think it’s a bit risky to provide new annotations without building on the substantial work already existing.

I thought the book was strongest when selecting lesser-known games and there are pleasingly quite a few of these! I always like when a game selection opens your eyes to a struggle that had passed you by all these years and that was certainly the case with the selection of games from the Marshall-Capablanca match of 1909. It was such a disaster for Marshall – he lost heavily to a player he’d expected to be a ‘pushover’! – that I assumed that the games were very one-sided and therefore of little interest. They were indeed quite one-sided but to dismiss them is to underestimate Marshall’s tremendous ingenuity, which simply foundered on a high level of accuracy and stability on Capablanca’s part.

Frank Marshall

Jose Raul Capablanca

New York 1909, game 11

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.♘c3 ♘f6 4.♗g5 ♗e7 5.e3 ♘e4

A favourite of Capablanca’s in this match, essentially a Lasker Variation without ...h6. Perhaps Capablanca was wary of provoking Marshall into taking on f6, as Marshall had won a number of games in this manner. In any case, it’s a good idea to take away a couple of minor pieces from a confirmed attacker!

6.♗xe7 ♕xe7 7.♗d3 ♘xc3 8.bxc3

Marshall had also reached this position in his less successful match against Lasker in 1907, and he’d encountered it earlier in this match as well. It seems Marshall liked his systems!

8...dxc4 9.♗xc4 b6

Looks slightly odd, as it allows White to play ♕f3 and force ...c6, but since Black will play ...♗b7 and ...c5, it’s perfectly fine.

10.♕f3 c6 11.♘e2 ♗b7 12.0-0 0-0 13.a4 c5 14.♕g3 ♘c6 15.♘f4 ♖ac8 16.♗a2 ♖fd8 17.♖fe1 ♘a5 18.♖ad1 ♗c6 19.♕g4

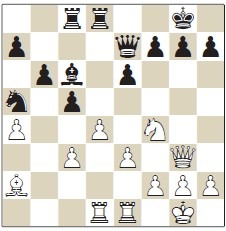

19.♕g4

‘Frankly, Frank, I’m impressed by your devious mind’, says Lakdawala!

19...c4 20.d5

Once again exploiting the x-ray attack of the queen on the rook on c8. We’re in the classic match scenario where Marshall is overplaying his hand, keeping things going with great ingenuity, while Capablanca keeps batting away the threats with a high degree of accuracy.

20...♗xa4

Even 20...exd5 21.♘xd5 ♗xd5, ‘falling into’ Marshall’s trap, was pretty good for Black after 22.♖xd5 ♖xd5 23.♕xc8+ ♕d8. However, Capablanca’s move is even stronger according to the engines.

21.♖d2 e5 22.♘h5 g6 23.d6

Another trick against the rook on c8!

23...♕e6 24.♕g5 ♔h8 24...♕f5 is pointed out by Lakdawala and would seem to be a very Capablanca-ish thing to do, exchanging queens to break the attack! The text gives Marshall’s faltering initiative a fresh impetus, but he’d need to find a remarkable idea to prove it!

24...♕f5 is pointed out by Lakdawala and would seem to be a very Capablanca-ish thing to do, exchanging queens to break the attack! The text gives Marshall’s faltering initiative a fresh impetus, but he’d need to find a remarkable idea to prove it!

25.♘f6

The great shot pointed out by Lakdawala is 25.f4 gxh5 26.f5 f6 27.fxe6 fxg5 28.e7 ♖e8 29.♖f1 ♔g7 30.♗b1, when the threats of both ♖df2-f7+ and d7 keep White afloat!

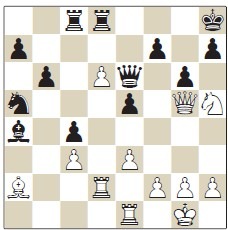

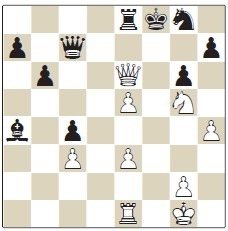

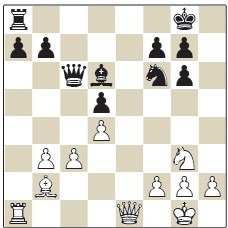

25...♖xd6 26.♖xd6 ♕xd6 27.♗b1 ♘c6 28.♗f5 ♖d8 29.h4

29.h4

The engines and Lakdawala again point out a quite stunning resource: 29.♗d7, when 29...♖xd7 30.♕h6 mates after 30...♕xf6 31.♕f8. This tactic makes it peculiarly difficult for Black to eject the white minor pieces from their ridiculously exposed posts, while the bishop on d7 also pins the knight on c6 to the bishop on a4. I’ve truly never seen anything like this before! White also has ideas of ♘e8 in the air so the engines see nothing more than a draw.

29...♘e7 30.♘e4 ♕c7 31.♕f6+ ♔g8

White’s pieces look dangerous but White is in danger of getting pushed back.

32.♗e6

After 32.♗h3 ♘d5 33.♕g5 ♗c2, there is nothing left of White’s attack. Therefore, Marshall decides to gamble some more!

32...fxe6 33.♕xe6+ ♔f8 34.♘g5 ♘g8 35.f4 ♖e8 36.fxe5 36...♖e7

36...♖e7

Another only-move from Capablanca! Both Marshall’s inventiveness and Capablanca’s calmness are extremely impressive!

37.♖f1+ ♔g7 38.h5 ♗e8

Another lovely move to reinforce the kingside and bring the offside bishop back into play. It’s only 1909, but you feel tempted to talk about engine-like defence!

39.h6+ ♔h8 40.♕d6 ♕c5 41.♕d4 ♖xe5

No fear again! The pin along the a1-h8 diagonal doesn’t matter when Black can exchange queens.

42.♕d7

A great little final shot, threatening ♕g7+mate! Marshall would have been a demon at bullet chess!

42...♖e7

42...♗xd7 43.♘f7 mate.

43.♖f7 ♗xd7 0-1.

A very pleasant read in conclusion. Somewhere between 3 and 4 stars for me, but I’ll stick to 3 this time!

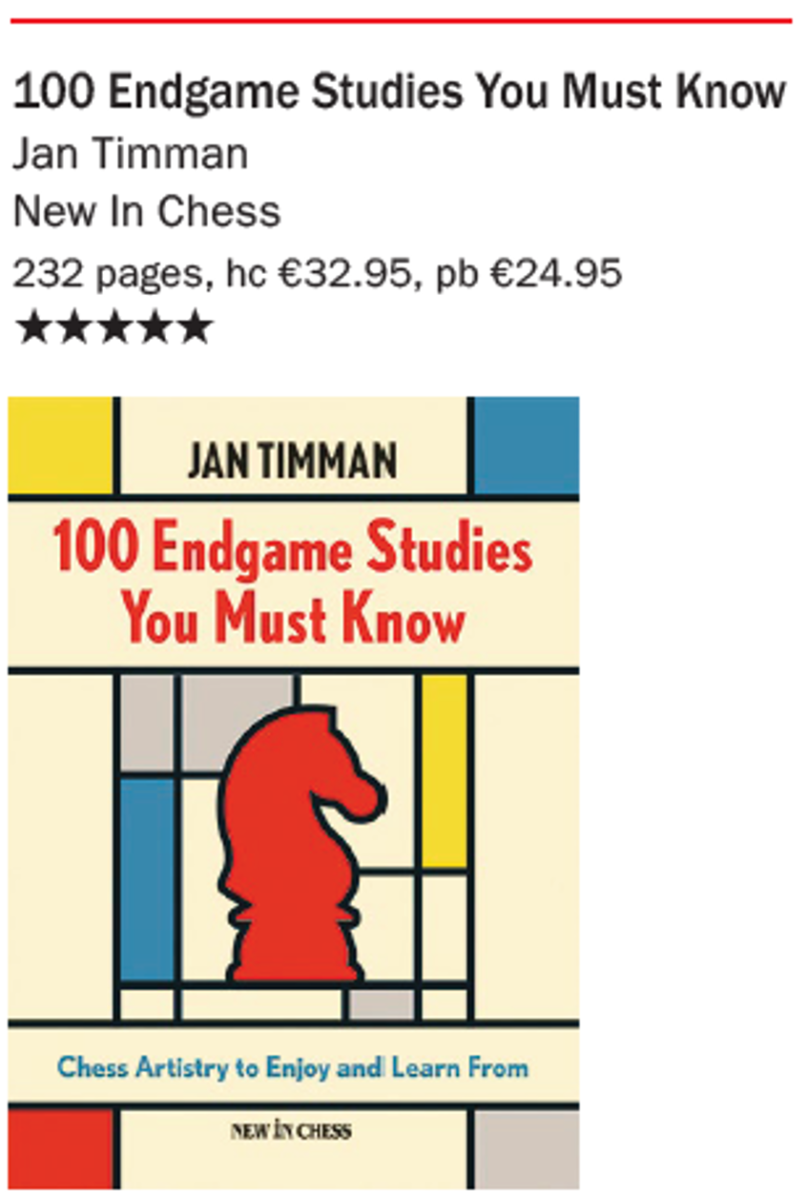

Two rather accusatory titles from New in Chess up next! We’ll start with Jan Timman’s latest 100 Endgame Studies You Must Know. The words ‘must know’ or ‘should know’ always awaken a terrible feeling of guilt in me, but having got over that, I had a great time with this book!

Two rather accusatory titles from New in Chess up next! We’ll start with Jan Timman’s latest 100 Endgame Studies You Must Know. The words ‘must know’ or ‘should know’ always awaken a terrible feeling of guilt in me, but having got over that, I had a great time with this book! The idea is extremely simple and very nice. Bring 100 studies with plenty of appeal for practical players together, put a huge diagram and a little introduction and background on the composer from Jan Timman on the left-hand page, and the solution on the right-hand page with extra little small diagrams where appropriate! Jan always writes very well about studies, with a keen eye for the points and details that will appeal to practical players: the ‘ooohs’ and ‘aaahs’ come very easily when reading through this book. I confess I didn’t even try to solve any of the puzzles: I just played through them all with a smile on my face! I’m afraid that to give you a taste of the content, I’m going to have to ruin one of the studies for you, but I can assure you the other 99 are well worth the price!

The idea is extremely simple and very nice. Bring 100 studies with plenty of appeal for practical players together, put a huge diagram and a little introduction and background on the composer from Jan Timman on the left-hand page, and the solution on the right-hand page with extra little small diagrams where appropriate! Jan always writes very well about studies, with a keen eye for the points and details that will appeal to practical players: the ‘ooohs’ and ‘aaahs’ come very easily when reading through this book. I confess I didn’t even try to solve any of the puzzles: I just played through them all with a smile on my face! I’m afraid that to give you a taste of the content, I’m going to have to ruin one of the studies for you, but I can assure you the other 99 are well worth the price!

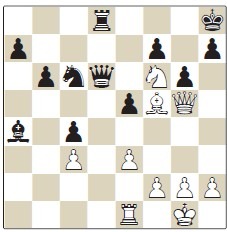

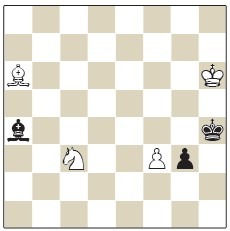

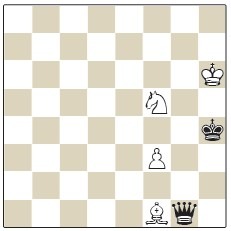

Pogosyants 1961 White to play and win

White to play and win

I love studies where my initial reaction is ‘Well this can never be anything for White!’ This one is by Ernest Pogosyants (1935-1990) who as Timman explains ‘was the most productive study composer ever. He has more than two thousand studies in the database. This had to do with the fact that for many years he had a daily column in a Russian newspaper, in which he published a new chess puzzle every day for years.’

White has to stop the g-pawn to start with and the other things to notice are that Black’s bishop on a4 is attacked and that Black’s king is short of squares.

1.♗f1 ♗c6 2.♘e4

The first trap to avoid! 2.♗g2 ♗xf3 3.♗xf3 ♔h3 4.♘e2 g2 followed by ...♔h2 leads to a draw: 5.♘f4+ ♔g3.

2...♗b5 3.♗g2

3.♗xb5 g2.

3...♗f1

A point where as an inexperienced solver you might stop and think that you need to look earlier for White. Because after:

4.♗xf1 g2 Black is surely achieving a draw, as 5.♗xg2 is stalemate! White however has a reply that truly defies belief! Solution at the end of the article!

Black is surely achieving a draw, as 5.♗xg2 is stalemate! White however has a reply that truly defies belief! Solution at the end of the article!

A really nice book! I’m a bit worried I’m going over the top with 5 stars this week, but I fear this one deserves it! 5 stars!

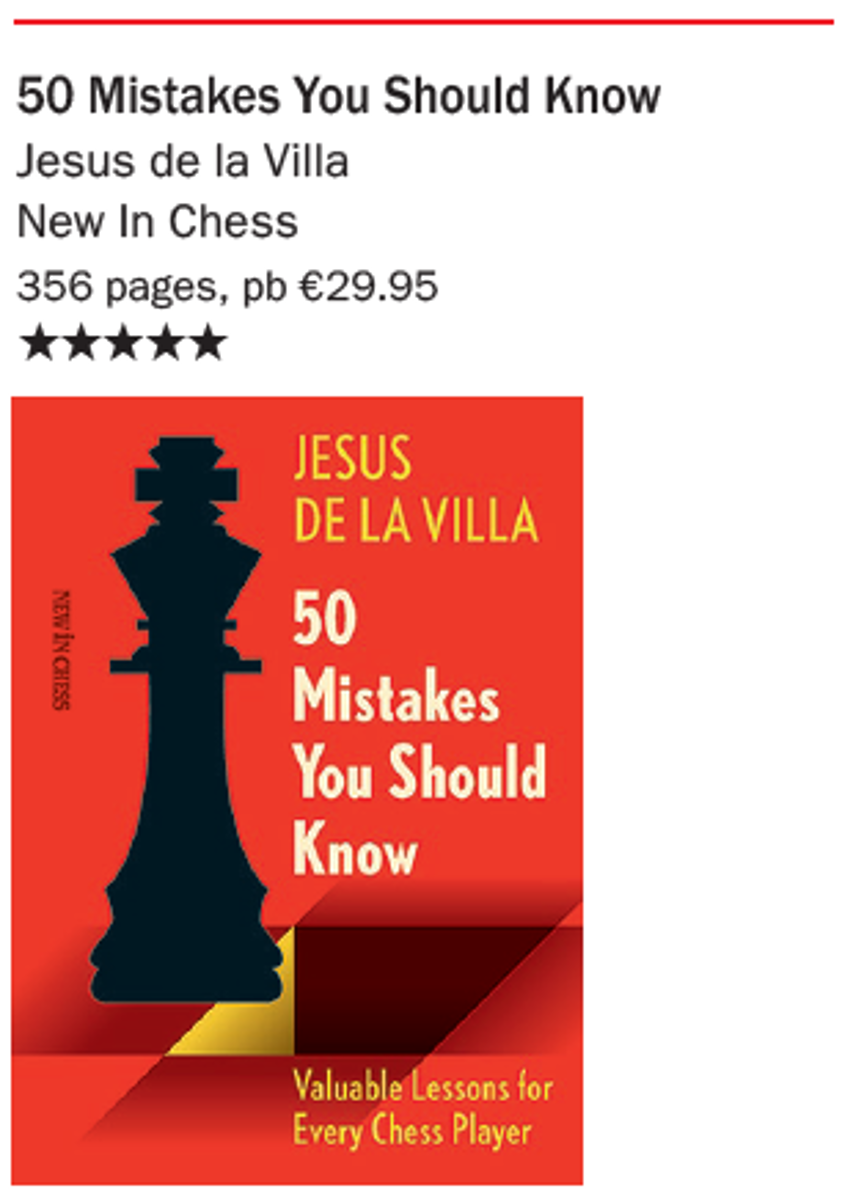

Jesus de la Villa’s 100 Endgames You Must Know (you can see where New In Chess borrowed Timman’s title from!) is a classic endgame manual, that I’ve recommended to everyone over the years so I was intrigued to see what 50 mistakes You Should Know (New In Chess) would be like. It’s a big book – 350 pages – with De la Villa’s 50 typical mistakes grouped into twelve chapters, such as ‘Exchanging Pieces’, ‘Positional Sacrifices’ and ‘Rook Endings’. A key feature is that all the examples in the books are taken from games by amateurs, ensuring that the errors examined really are relevant to the general chess population rather than the elite few! Each chapter starts with a small set of puzzles where you have to make a choice of move, and from time to time one of those puzzles pops up in the chapter and you can see whether you made a typical mistake or whether you sidestepped it (hopefully on purpose!)

Jesus de la Villa’s 100 Endgames You Must Know (you can see where New In Chess borrowed Timman’s title from!) is a classic endgame manual, that I’ve recommended to everyone over the years so I was intrigued to see what 50 mistakes You Should Know (New In Chess) would be like. It’s a big book – 350 pages – with De la Villa’s 50 typical mistakes grouped into twelve chapters, such as ‘Exchanging Pieces’, ‘Positional Sacrifices’ and ‘Rook Endings’. A key feature is that all the examples in the books are taken from games by amateurs, ensuring that the errors examined really are relevant to the general chess population rather than the elite few! Each chapter starts with a small set of puzzles where you have to make a choice of move, and from time to time one of those puzzles pops up in the chapter and you can see whether you made a typical mistake or whether you sidestepped it (hopefully on purpose!)

I really liked this book. Quite apart from the explicit analysis of positions and mistakes, which is excellent, there is a huge amount of quite profound advice about mistakes which you’d normally only discover through a lot of pain and grief! For example, this lovely paragraph right at the start of the book really spoke to me: ‘Even before playing chess, we heard pearls of popular wisdom about the importance of errors in learning processes, such as the classic saying: “The human being is the only animal that trips over the same stone twice”. Its origin is unknown, but we can be sure that the first person to say it was not a chess player, because if he had been, he would have replaced “twice” with a bigger number. We chess players have soon discovered that making the same error twice is not enough for us to learn the lesson; perhaps two dozen is closer to reality.’ It’s something that you don’t like to admit to yourself (you feel stupid) but seeing it written down makes it feel less shameful! I also very much liked the definitions of concepts at the start of the book which really help to mentally capture key moments in the game. For example ‘Irreversible moves’ which De la Villa defines as ‘Moves from which there is no going back. There are just three types, of which the third is the least forceful conceptually, although just as definitive in practice: pawn advances, piece exchanges and castling’. Every chess player is aware of the maxim that ‘pawns cannot move backwards’, but I’d never seen piece exchanges and castling put into the same category before.

I also very much liked the definitions of concepts at the start of the book which really help to mentally capture key moments in the game. For example ‘Irreversible moves’ which De la Villa defines as ‘Moves from which there is no going back. There are just three types, of which the third is the least forceful conceptually, although just as definitive in practice: pawn advances, piece exchanges and castling’. Every chess player is aware of the maxim that ‘pawns cannot move backwards’, but I’d never seen piece exchanges and castling put into the same category before.

Another lovely concept is ‘New or emerging tactic’, which De la Villa defines as ‘a tactic for our opponent that appears as a consequence of our last move’. The sensation of not seeing any danger, making a move, and then seeing that you have unwittingly ‘armed’ a previously harmless or non-existent tactic is gruesomely familiar and this concept captures it perfectly. I also had a ‘wow’ moment when playing through this example on exchanging:

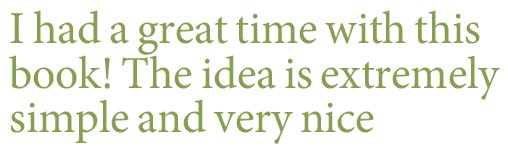

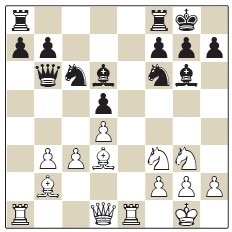

Ana Redondo

Julio Suarez

Spain U16 2014 Here White initiated a series of exchanges which turn the position from equal to clearly worse.

Here White initiated a series of exchanges which turn the position from equal to clearly worse.

16.♗xg6 hxg6 17.♘e5 ♖fe8 18.♘xc6 ♖xe1+ 19.♕xe1 ♕xc6 19...♕xb3 is even stronger but the game move also assures Black a clear advantage.

19...♕xb3 is even stronger but the game move also assures Black a clear advantage.

De la Villa’s throwaway comment is really perceptive: ‘White has exchanged three pieces but they were her best ones, which are usually the easiest to exchange’. That’s it – that’s the key phrase I’ve been looking for all these years! That’s how you can explain to a player why such a course of action seems tempting (you have the power to do it and you feel therefore that you are dictating the play) and also why you shouldn’t do it!

In summary, I think this book is just as good as De la Villa’s endgame book, which is quite some praise. A must for any player looking to understand how to improve and where to look for mistakes to improve! 5 stars!

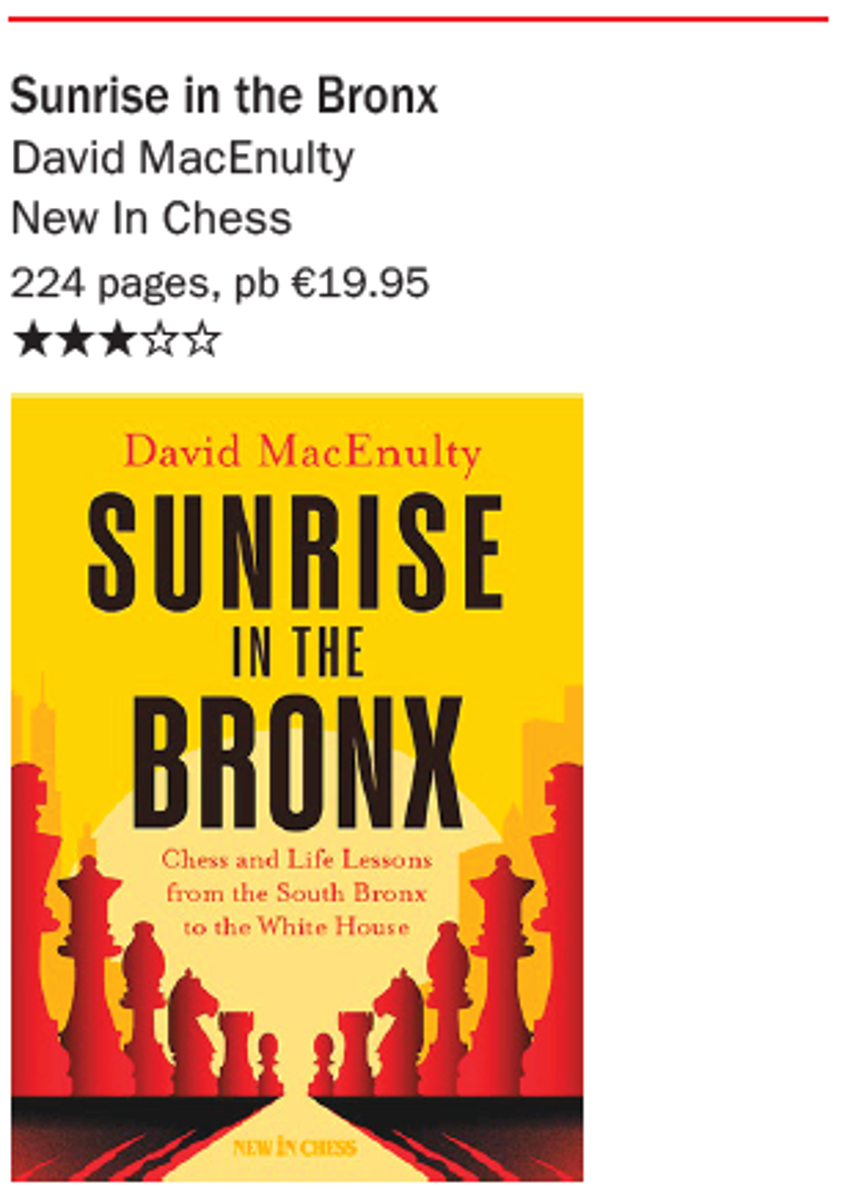

We finish with Sunrise in the Bronx by David MacEnulty (New In Chess), which is an inspirational account of the experiences of a chess teacher at an elementary school in the Bronx.

We finish with Sunrise in the Bronx by David MacEnulty (New In Chess), which is an inspirational account of the experiences of a chess teacher at an elementary school in the Bronx.

It started with a one-off request from long-time friend Bruce Pandolfini to take over a chess lesson and ended in a full-time job teaching chess, taking children from the slightest chess knowledge to winning national school competitions against vastly better-financed schools. I read it just after reading 50 Mistakes You Should Know and oddly enough I found echoes of the former book in Sunrise in the Bronx as the author explains the mistakes he made when thrown in at the deep end, and how he gradually improved his teaching technique. One particularly striking passage is when the author describes how he became aware of how careful he needed to be when making assumptions about prior knowledge. He describes showing a chessboard and talking about corners and gradually discovering that none of the children understood what he meant by ‘corner’. And then grappling all night searching for a way to start his lessons in a way that pupils would understand. It’s an engaging and inspiring story and you are rooting for MacEnulty’s charges all the way as they fight all the way to victory! A surprise amongst all the other books this month and a really nice one! 3 stars! ■

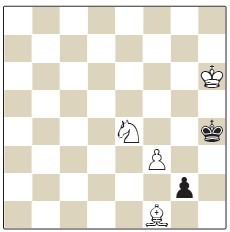

Solution Pogosyants 1961

5.♘g3

A move so good it should be made illegal!

5...g1♕

5...gxf1♕

6.♘xf1 and the black king cannot approach the f-pawn; 5...♔xg3 6.♗xg2 and the bishop defends the f-pawn, which queens after 6...♔xg2 7.f4.

6.♘f5 Mate. An astonishing mate!

An astonishing mate!