So confusing!

These book reviews by Matthew Sadler were published in New In Chess magazine 2024#8

The third volume of Viktor Korchnoi’s biography still does not bring clarity. So many things happen in Korchnoi’s games that they are sometimes very difficult to understand.

It’s a strange feeling to read a modern repertoire book, Queen’s Gambit Accepted by Nicolas Yap, about an opening you have known extremely well, only to discover that every recommendation would have been considered completely unsound in your day! In all fairness, none of Yap’s lines are particularly well-known even a year after the publication of the book, but they have been played by super-grandmasters on various occasions.

It’s a strange feeling to read a modern repertoire book, Queen’s Gambit Accepted by Nicolas Yap, about an opening you have known extremely well, only to discover that every recommendation would have been considered completely unsound in your day! In all fairness, none of Yap’s lines are particularly well-known even a year after the publication of the book, but they have been played by super-grandmasters on various occasions.

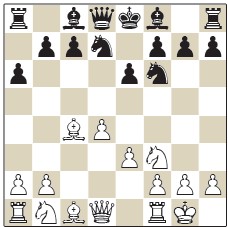

It’s always an interesting question for an older player like me to ponder why certain possibilities remained hidden to us in the pre-computer age, despite intensive analysis of that opening over many years. I certainly thought a few times about meeting 1.d4 d5 2.c4 dxc4 3.e4 with 3...b5, but why did I already lose hope and interest after 4.a4 c6 5.axb5 cxb5 6.♘c3? I spent a little time on 6...♕b6 (Yap’s recommendation), but assumed 7.♘d5 followed by 8.♗f4 was crushing

I spent a little time on 6...♕b6 (Yap’s recommendation), but assumed 7.♘d5 followed by 8.♗f4 was crushing I looked at 6...♗d7, but didn’t like 7.d5, and of course the much-examined modern exchange sacrifice 6...a6 7.♘xb5 axb5 8.♖xa8 ♗b7 escaped my attention completely!

I looked at 6...♗d7, but didn’t like 7.d5, and of course the much-examined modern exchange sacrifice 6...a6 7.♘xb5 axb5 8.♖xa8 ♗b7 escaped my attention completely!

My feeling is that it was linked to the amount of complexity that you had to process at the initial moment of spotting a possibility. I think that professionals of my era could accept the idea of needing to solve a couple of unclear variations – without an engine, of course! – to make an opening idea work. However, some early encouragement – a couple of lines that you solved quickly, ideally through an elegant tactical nuance – was needed to motivate you to invest your precious time into uncharted waters, instead of fine-tuning existing ‘respectable’ theory.

For example, 6...♕b6 is purely complexity. Even if you find something against 7.♘d5 ♕b7 8.♗f4 (which is far from obvious), you still have to wade through 7.b3 (undermining the pawn chain), 7.♗e3 (to uncover an attack on the black queen with d5), or even just 7.♘f3, developing and holding back b3 and ♗e3 until a later, maybe more awkward moment. And if you spot 7.♕h5 – hitting b5 in an uncomfortable way – then there is even more to worry about. It’s simply too much!

The risk that one of those lines would turn out to be unplayable – and that your analysis of other lines would turn out to be a week or two of wasted time – was too great. Obviously, in the engine era, none of this initial discovery has any impact on your time: you start the engine somewhere and go live your life! After a couple of hours, you come back and already have preparation that would have cost you a month of effort in the pre-computer age! I guess it’s an example of how ‘a lack of processing power’ – to describe a grandmaster in the pre-engine era 12 – can stifle innovation!

What I really liked about Yap’s book is that the lines he recommends are consistent in approach against all of White’s possibilities. After all, why spend hours learning sharp lines in the Queen’s Gambit Accepted against 3.e4 if White can simply exchange queens with Kramnik’s favourite 1.d4 d5 2.c4 dxc4 3.♘f3 ♘f6 4.e3 e6 5.♗xc4 c5 6.0-0 a6 7.dxc5 and maintain a small, annoying edge without much effort? Yap tries very hard to make queen-exchange avoiding lines, such as 5...a6 6.0-0 ♘bd7 or 6.a4 b6, work, which means you have a maximally sharp repertoire across the entire opening.

or 6.a4 b6, work, which means you have a maximally sharp repertoire across the entire opening.

One thing that made me smile was the recommendation of 1.d4 d5 2.c4 dxc4 3.e3 e5 4.♗xc4 ♘c6!?, which transposes after 5.♘f3 e4 6.♕b3 ♘h6 7.♘fd2 f5 into a bananas game Bogoljubov-Leonhardt I analysed a little while back on my channel. Funny how a random classic game can suddenly become a main line in a book written in 2023!

In conclusion, a really interesting book. Not necessarily what you’d expect from the solid Queen’s Gambit Accepted but all the more interesting for it! 4 stars!

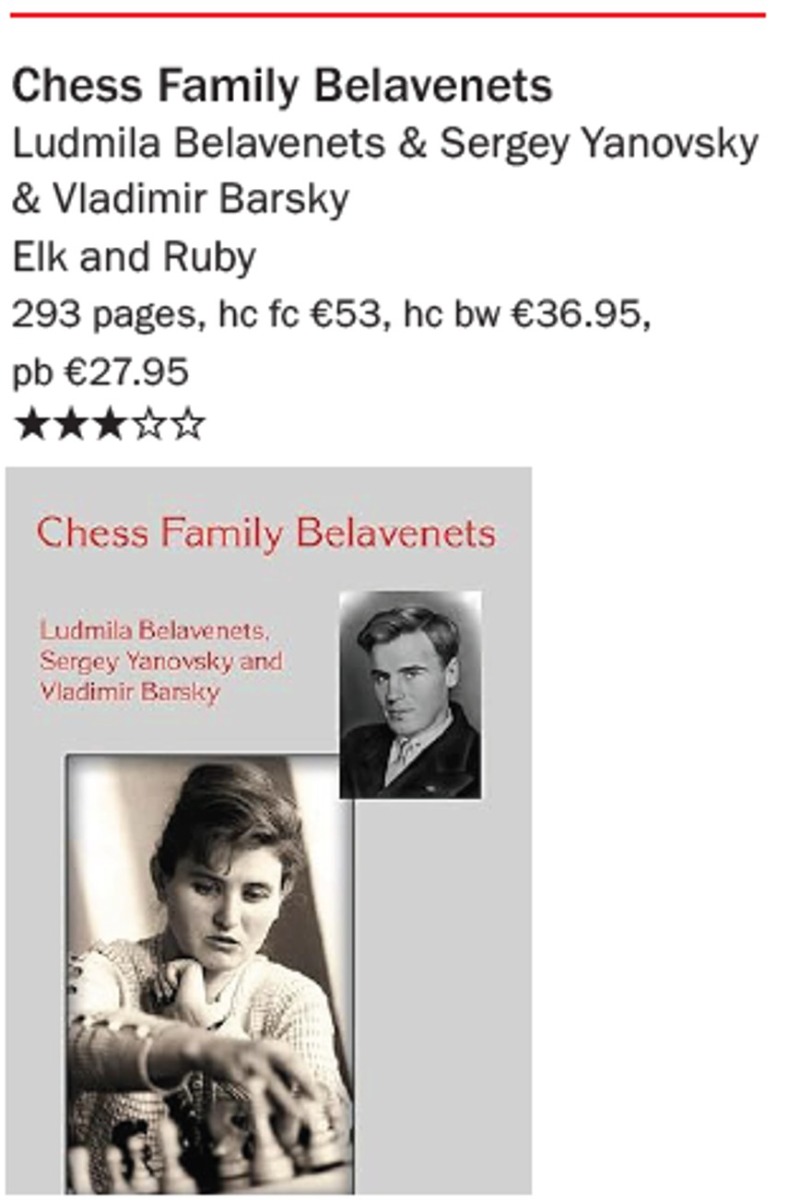

The next book, Chess Family Belavenets, by Ludmila Belavenets, Sergey Yanovsky and Vladimir Barsky gathers together various sources about the Belavenets chess-playing family.

The next book, Chess Family Belavenets, by Ludmila Belavenets, Sergey Yanovsky and Vladimir Barsky gathers together various sources about the Belavenets chess-playing family.

Sergei Belavenets was a strong Soviet master who died in 1942 at the young age of 32. His daughter Ludmila was a strong Soviet player and coach.

The book is comprised of Ludmila’s reminiscences of her father and chess career, accompanied by many family photos, the remnants (70 pages – the rest is lost) of the manuscript for a middlegame and endgame textbook that Sergei Belavenets prepared, and selected games of both Sergei and Ludmila. By the way, the section of the textbook on the endgame was quoted approvingly many times in the famous endgame book by Mikhail Shereshevsky, Endgame Strategy. Belavenets was the one to coin and explain the now-famous endgame principle: Do not hurry!

By the way, the section of the textbook on the endgame was quoted approvingly many times in the famous endgame book by Mikhail Shereshevsky, Endgame Strategy. Belavenets was the one to coin and explain the now-famous endgame principle: Do not hurry!

My thoughts about analysing in the pre-computer age and the danger of wasting time on useless analytical enterprises, were triggered again while reading the memoirs of Sergei Belavenets’ friend Mikhail Yudovich. Yudovich recalled their disagreement about the merits of the King’s Gambit line 1.e4 e5 2.f4 f5?!, which Belavenets liked but Yudovich found unimpressive. He wrote: ‘We decided to check the line in our next tournament game, and as luck would have it, Belavenets had White. What could we do? With his characteristic ingenuity, Belavenets immediately found the way. Our game started the following way: 1.e3 e5 2.e4 d5 3.f4! After a fierce struggle, the game was ultimately drawn. That’s how we went forward, down the hard road of chess mastery.’

which Belavenets liked but Yudovich found unimpressive. He wrote: ‘We decided to check the line in our next tournament game, and as luck would have it, Belavenets had White. What could we do? With his characteristic ingenuity, Belavenets immediately found the way. Our game started the following way: 1.e3 e5 2.e4 d5 3.f4! After a fierce struggle, the game was ultimately drawn. That’s how we went forward, down the hard road of chess mastery.’

I let my engines loose on 2...f5, by the way, and I’m afraid Yudovich was right!

It’s a nice book for fans of this era, filling in yet another gap in common knowledge about the lesser-known stars of this fascinating period in chess history. 3 stars!

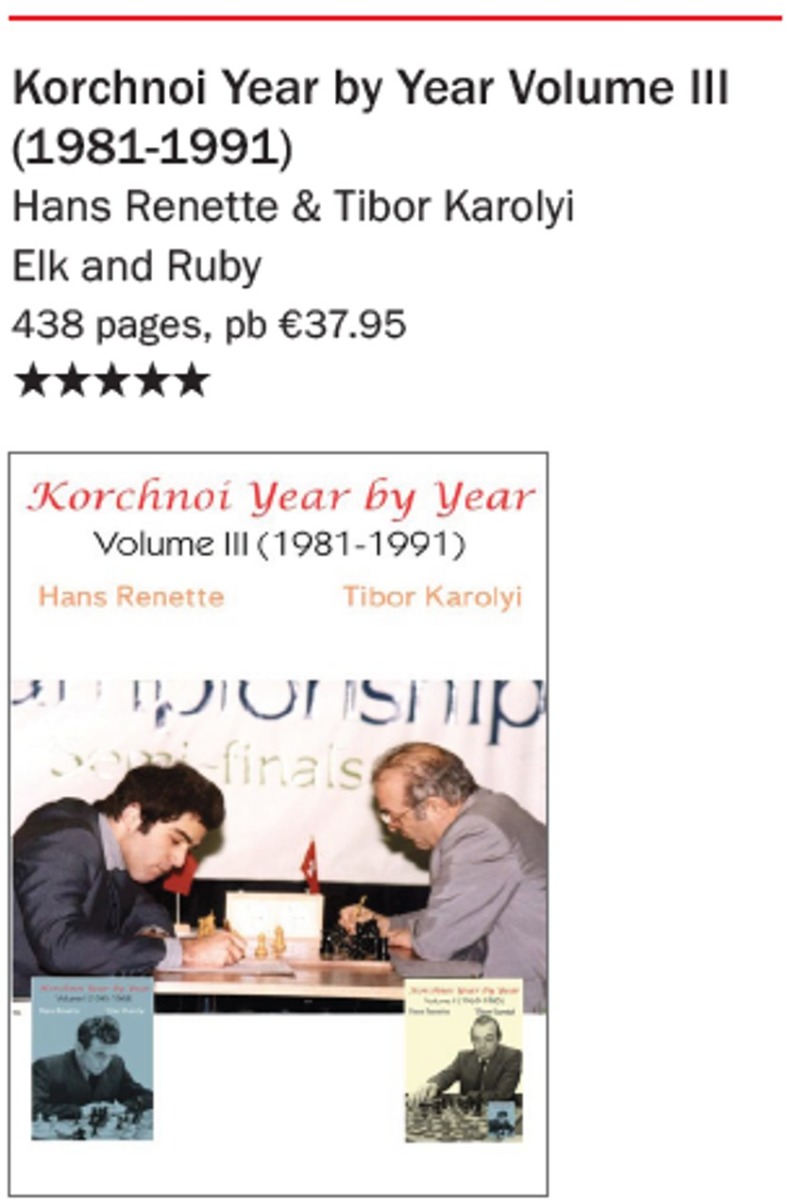

Korchnoi Year by Year Volume III (1981-1991) by Hans Renette and Tibor Karolyi continues the story of perhaps the most extraordinary player of recent times. We start with the disastrous 1981 World Championship match in Merano and navigate through ten years of relentless chess activity around the globe, as all manner of opponents were hammered into submission by any means possible! The book is the normal mix of annotated games, tournament reports, and additional anecdotes from contemporary players.

Korchnoi Year by Year Volume III (1981-1991) by Hans Renette and Tibor Karolyi continues the story of perhaps the most extraordinary player of recent times. We start with the disastrous 1981 World Championship match in Merano and navigate through ten years of relentless chess activity around the globe, as all manner of opponents were hammered into submission by any means possible! The book is the normal mix of annotated games, tournament reports, and additional anecdotes from contemporary players.

The thing about Korchnoi is that he played so many fighting games that there is never a shortage of littleknown incident-packed games to enjoy! I’m still struggling to appreciate Viktor’s games in the same way that I enjoy the games of other great players – so many things happen that if I’m honest, I find impossible to understand! Perhaps I can illustrate my confusion with this fragment from a game against the great Lev Polugaevsky in Biel 1986.

Viktor Korchnoi

Lev Polugaevsky

Biel 1986

English Opening

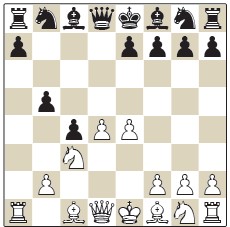

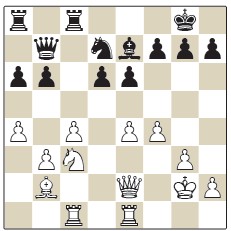

1.♘f3 c5 2.c4 ♘f6 3.♘c3 e6 4.g3 b6 5.♗g2 ♗b7 6.0-0 d6 7.b3 ♗e7 8.d4 cxd4 9.♘xd4 ♗xg2 10.♔xg2 ♕c7 11.e4 a6 12.♗b2 ♕b7 13.♖e1 0-0 14.♕e2 ♖c8 15.f4 ♘c6 16.♘xc6 ♕xc6 17.♖ac1 ♕b7 18.a4 ♘d7 This Hedgehog structure has turned out quite well for Black. In particular, the exchange of a pair of minor pieces eases Black’s cramped position.

This Hedgehog structure has turned out quite well for Black. In particular, the exchange of a pair of minor pieces eases Black’s cramped position.

Sometimes, the exchange of pieces can restrict Black’s ability to create counterplay with ...b5 or ...d5, but White has a number of sensitive light squares. Playing f4 early has left the e4-pawn bereft of pawn support, while the b3-pawn is vulnerable to ...♘c5.

My instinctive reaction as White would be to somehow cover everything. Korchnoi... just ignores everything, making moves that at first sight seem pretty random!

19.♔h3

I understand the king is moving out of the pin on the e4-pawn, but it doesn’t look great here either!

19...♘c5

Pressing the sensitive queenside light squares by attacking the b3-pawn.

20.b4

No defence! Korchnoi simply weakens his pawn chain – the c4-pawn loses its pawn support – and goes on the attack! There’s something so random to me about making two such moves on opposite sides of the board!

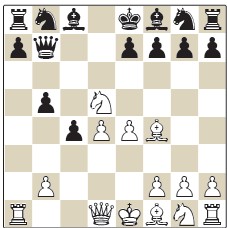

20...♘b3

20...♘d7 feels like a more typical Hedgehog move, retreating safely behind Black’s ‘spines’ after triggering a loosening in White’s position.

Perhaps the disconnected feel of Korchnoi’s last two moves led Polugaevsky into this aggressive continuation. It’s really high risk though as the knight on b3 is close to being trapped and not difficult to attack.

21.♖cd1 ♕c7 22.♘a2

22.♘a2

It turns out that 22...♕xc4 23.♕xc4 ♖xc4 24.♖d3 wins the knight! The value of 19.♔h3 is now seen as Black no longer has ...♖c2 with check!

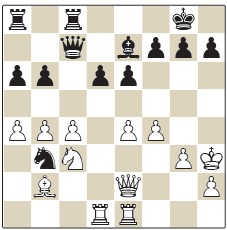

22...♕c6 23.f5 e5

This makes sure that the knight on b3 can always escape to d4 (albeit with the likely loss of a pawn) but weakens the d5-square terribly.

24.♘c3 ♕xc4 25.♕g4 f6 26.♘d5 After moves like 20.b4 and 22.♘a2, White suddenly has a kingside initiative!

After moves like 20.b4 and 22.♘a2, White suddenly has a kingside initiative!

26...♗d8 27.♖e3 ♕c2 28.♗c3 ♖c6 29.♕h5 A really unpleasant move for Black’s disconnected forces to parry. The queen on c2 and the knight on b3 are cut off from Black’s position while the bishop on d8 prevents the rook on a8 from assisting the king. Somehow Korchnoi’s moves have ended up making perfect sense, leading to a highly-coordinated position!

A really unpleasant move for Black’s disconnected forces to parry. The queen on c2 and the knight on b3 are cut off from Black’s position while the bishop on d8 prevents the rook on a8 from assisting the king. Somehow Korchnoi’s moves have ended up making perfect sense, leading to a highly-coordinated position!

29...♔f8 30.♖ed3 ♖ac8 31.♘e3 ♕a2 32.♕xh7 ♖xc3 33.♕h8+ ♔f7 34.♖xc3 ♖xc3 35.♕xd8 ♕e2 36.♕d7+ ♔g8 37.♕e8+ ♔h7 38.♖xd6 ♖c8 39.♕g6+ ♔h8 40.♖d7 ♖g8 41.♘g4

1-0.

So confusing! A wonderful collection of fighting chess! 5 stars!

Karsten Müller continues his series of middlegame training books with Typical King’s Indian: Effective Middlegame Training. The approach remains the same as ever: 100 middlegame exercises from games, organised around typical pawn structures arising from the opening. The exercises are quite varied. Sometimes you are asked to evaluate one move, sometimes you have to choose between two candidate moves, and sometimes you have to think of a continuation all by yourself!

Karsten Müller continues his series of middlegame training books with Typical King’s Indian: Effective Middlegame Training. The approach remains the same as ever: 100 middlegame exercises from games, organised around typical pawn structures arising from the opening. The exercises are quite varied. Sometimes you are asked to evaluate one move, sometimes you have to choose between two candidate moves, and sometimes you have to think of a continuation all by yourself! Some openings fit this approach better than others but I felt that this King’s Indian book works really well. Let me just give one example (I hope that won’t ruin it for anyone: still 99 others to do!)

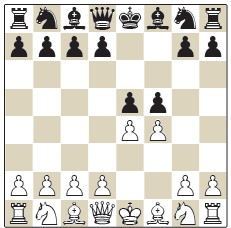

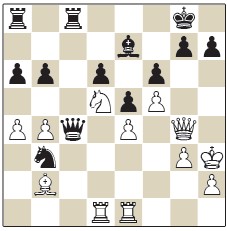

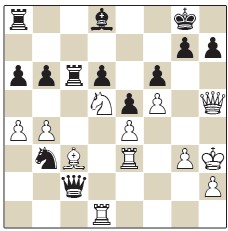

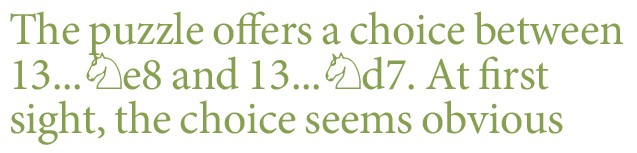

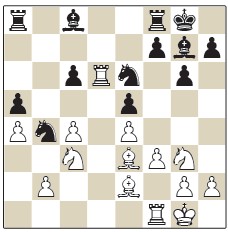

Some openings fit this approach better than others but I felt that this King’s Indian book works really well. Let me just give one example (I hope that won’t ruin it for anyone: still 99 others to do!) The puzzle here is a choice between two moves: 13...♘e8 and 13...♘d7. At first sight, the choice seems obvious.

The puzzle here is a choice between two moves: 13...♘e8 and 13...♘d7. At first sight, the choice seems obvious.

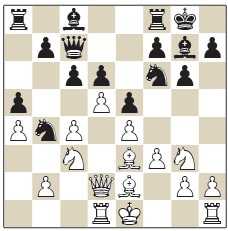

After 13.d5, White is threatening to capture on c6 and then capture on d6, winning a pawn. However, Müller points out the difference in activity between White’s knight on g3 and the black knight on b4 and also notes that dxc6 ...bxc6 will open the b-file for Black for counterplay against White’s backward b2-pawn. From d7, the knight is heading to c5, which is a more active post than Black can find from e8!

13...♘d7 14.dxc6 bxc6 15.0-0

15.♕xd6 ♘c2+ 16.♔f2 ♕b7 is very awkward for White!

15...♘c5 16.♕xd6 ♕xd6 17.♖xd6 ♘e6 This gives Black good compensation for the pawn, due to Black’s excellent control of the central dark squares and potential pressure along the b-file.

This gives Black good compensation for the pawn, due to Black’s excellent control of the central dark squares and potential pressure along the b-file.

All-in-all a very welcome additional training method for both those who play and face the King’s Indian! 4 stars! ■