The difference between theory and practice

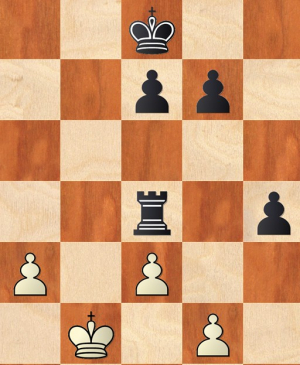

The difference between endgame theory and practice can sometimes prove to be very difficult. Even the greatest players in the world in several cases go wrong in making decisions that are sometimes taken for granted by the outside world. For example, I think most strong chess players in rook endgames are familiar with the principle of the “shoulder budge” which played a significant role in the famous example Alekhine – Bogoljubow (1929) in which the black player made a historic blunder by taking the wrong “turn” with his king causing him to miserably lose the remaining endgame of rook against pawn. In my book, I refer to this concept in the section on the endgame of “rook against pawn” (p. 94). Afterward, on p. 251, I draw attention to the aforementioned example from the 1929 World Cup game. How great then is my surprise when I see how the very respectable Croatian grandmaster Ivan Saric (didn't he once beat Magnus Carlsen beautifully in the 2014 Olympiad?) appears to have momentarily forgotten the principle of the shoulder budge in the following excerpt.

Foto: Johannes Grabmeier/SV Deggendorf

Foto: Johannes Grabmeier/SV Deggendorf

A very different fight took place in the next game (Firouzja – Caruana) in which, on the 56th move, the black player failed to make it easy for himself by putting his rook behind the only white (passed) pawn. Wasn’t Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch who taught us this rule? This led to white's pawn becoming a dangerous weapon while the two black passed pawns had not yet reached the back rank. After the white bishop and black knight went off the board, the rook endgame appeared to turn into a curious one with the black queen (and pawn) against the white rook (and pawn on the penultimate rank). At one point, Black had little choice but to passively put the queen in front of the pawn and try to force another promotion with his last pawn. Because of course, Firouzja did not sit still and stubbornly tried to force the promotion of his pawn. But a wrong rook move eventually led to an insanely difficult endgame that Caruana brilliantly managed to carry to victory. With the table bases, it can be shown that only a different rook move (65.Rd3!! instead of 65.Rd1?) could have led to a draw. The game showed several fine examples of various possible conversions (for example, to a queen’s endgame with a nice black pawn on g2 that the table bases give as a win) and where the American eventually won. It was a very captivating and instructive whole, where several important principles had to be applied in this endgame.

Photo: Lennart Ootes/Grand Chess Tour

Photo: Lennart Ootes/Grand Chess Tour

Conclusions:

Although the two fragments shown above are of a different nature, in both cases, we see clear parallels between where a strong player briefly loses “known laws” in an endgame and thus gets himself into trouble. Saric evidently forgot that in the remaining endgame of rook against pawn, he has to hold off the enemy king and that costs him half a point.Caruana fails, at a critical moment, to place the rook behind the opponent’s passed pawn, which could have saved him a very complicated endgame, which even at one point was a draw. That the American still won the game is extremely clever and it does show that his skill and calculation power in the endgame is phenomenal.