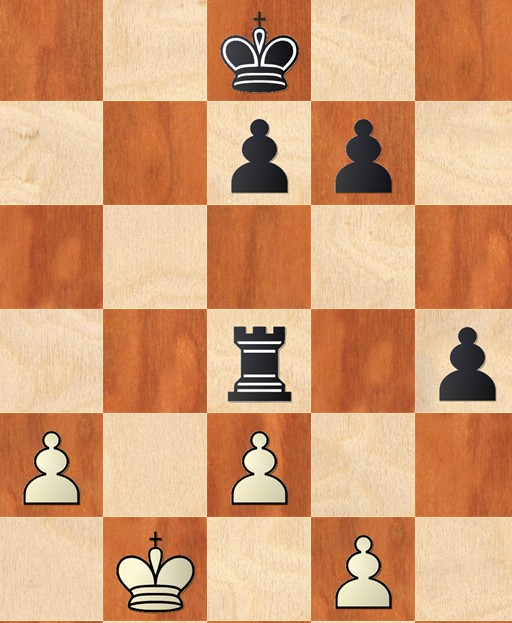

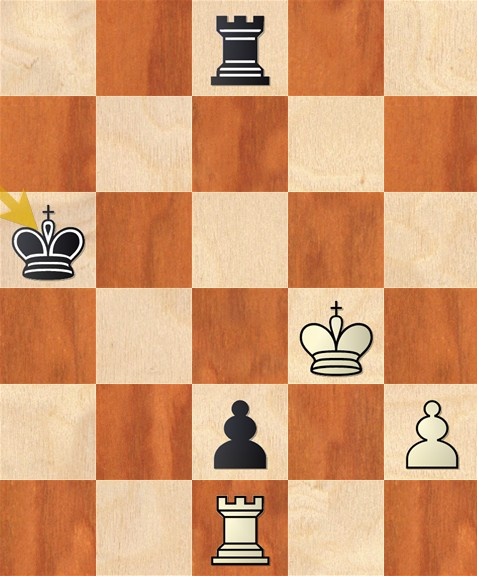

Revealing mistakes by a strong grandmaster

I have often noticed that even very experienced (top) grandmasters sometimes lack the knowledge of theoretical endgames. A lifetime simply contains too little time to learn everything that might be needed to play an endgame perfectly. Funnily enough, even in positions with very little material on the board, problems sometimes crop up that you wouldn't expect. The margin between win and draw is sometimes so close that it pays to delve into seemingly simple positions. I found two interesting cases where the strongest player had a very difficult time against an opponent that was (much) weaker on paper. In the Cambridge Open 2025 (in England), top British player Michael Adams (2661 and former world number four) played in the second round against Dutch player Marcel Schroer (with a modest rating of 2085). The rating difference was hardly reflected during the game so the game slipped into the endgame, in which both players had only one rook and one pawn each as of move 59. In the process, the175