Revealing mistakes by a strong grandmaster

I have often noticed that even very experienced (top) grandmasters sometimes lack the knowledge of theoretical endgames. A lifetime simply contains too little time to learn everything that might be needed to play an endgame perfectly. Funnily enough, even in positions with very little material on the board, problems sometimes crop up that you wouldn't expect. The margin between win and draw is sometimes so close that it pays to delve into seemingly simple positions. I found two interesting cases where the strongest player had a very difficult time against an opponent that was (much) weaker on paper.

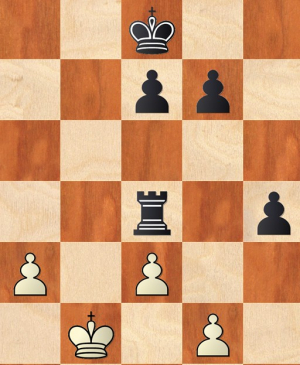

In the Cambridge Open 2025 (in England), top British player Michael Adams (2661 and former world number four) played in the second round against Dutch player Marcel Schroer (with a modest rating of 2085). The rating difference was hardly reflected during the game so the game slipped into the endgame, in which both players had only one rook and one pawn each as of move 59. In the process, the black one would quickly disappear from the board, after which a theoretically familiar endgame of rook and pawn against rook would come on the board. This had all the hallmarks of the endgame in which the infamous ‘rule of five’ was around the corner. For those unfamiliar with this rule of thumb, it is as follows: we count the rank on which the pawn stands and the number of files that the enemy king is cut off from the pawn. If the total is 5, the defender will usually be able to keep a draw. Is it 6 or higher, the stronger side will normally have achieved a winning position. But as my book explains on pages 270-285, there are also the necessary exceptions that therefore make this problem somewhat complicated.

Because in this case the pawn was still on the second rank and Black would put his rook in front of the enemy white pawn, the win was rather complicated. Especially also because it involved a white g-pawn and that there are disadvantages to that, even Adams didn't quite realize. In any case, Black could have made a draw, but he missed. After that, White had a winning position in his hands but he too went wrong. Perhaps Adams then realized he had messed up and he did a clever waiting move. That led to another mistake by his opponent, so the white player eventually walked away with the win. An interesting practice case!

In our second example, we see a pawn endgame that should have ended in a draw if played well but the narrow path to a nice result is not found by the white player.

In the position after 32...f7-f5, white slipped up on a pawn where he could have defended better. What follows is extremely instructive. The pawn duo a3/b2 is fixed by Ivanchuk with ...a5-a4. The white king has no time to remove that pawn from the board and, for that very reason, black's a4-pawn becomes the nail in white's coffin. The white king does get back in time to contain a black pawn breakthrough but in the remaining endgame black captures a pawn. Without pawns on the queen’s wing, this position would end in a draw but under these circumstances Ivanchuk can use the well-known stalemate trick. By trapping the white king, the latter is obliged to play up his b-pawn (with e.g. b2-b4) after which Black with ...a4xb3 (e.p.) allows this pawn to be promoted. We also saw this same theme in the Mostertman-Smeets game (from my first article in this mini-series).

In the position after 32...f7-f5, white slipped up on a pawn where he could have defended better. What follows is extremely instructive. The pawn duo a3/b2 is fixed by Ivanchuk with ...a5-a4. The white king has no time to remove that pawn from the board and, for that very reason, black's a4-pawn becomes the nail in white's coffin. The white king does get back in time to contain a black pawn breakthrough but in the remaining endgame black captures a pawn. Without pawns on the queen’s wing, this position would end in a draw but under these circumstances Ivanchuk can use the well-known stalemate trick. By trapping the white king, the latter is obliged to play up his b-pawn (with e.g. b2-b4) after which Black with ...a4xb3 (e.p.) allows this pawn to be promoted. We also saw this same theme in the Mostertman-Smeets game (from my first article in this mini-series).

Conclusions:

In the examples above, we see strong players (former world elite players) struggling against, on paper, weaker opponents. In the first example, Adams is left with only the endgame of rook and pawn against rook, with the opponent having placed his king on the wrong square just before. White then stands to win but finding it is far from easy. Indeed, Adams even hands over the win because he makes a mistake. A famous exception to the ‘Rule of Five’ appears to have arisen. But a clever waiting move brings him a full point in second when the opponent also makes another mistake and then allows the so-called ‘horizontal cut-off’.The second example shows us a pawn endgame that should be a draw if played well. The white player then mistakenly takes a black pawn off the board with his king, where he should have limited himself to playing a useful move first (33.b2-b4!) after which Ivanchuk (perhaps) could not have won. But that does not happen and then the legendary grandmaster seizes his chance and he plays the endgame flawlessly to victory. In doing so, he uses the ‘stalemate strategy’ in which the enemy king is stalemated and he has to play up a pawn with fatal results. Very instructive these two excerpts!