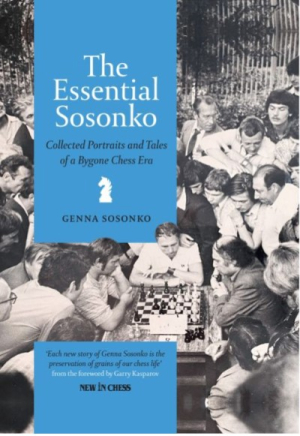

The Essential Sosonko - Smart Chip

'Each new story of Genna Sosonko is the preservation of grains of our chess life', says Garry Kasparov in the foreword.

We proudly present a one-volume collection of Genna Sosonko's best stories - essential reading for every chess fan interested in the history of chess and the heart and soul of chess players.

No other writer can tell you more about legends such as Mikhail Tal, Viktor Korchnoi, and David Bronstein or unforgettable personalities such as 'Chip' Chepukaitis and Sergey Nikolaev.

This monumental book is a collection of the portraits and profiles Sosonko wrote for New in Chess, plus 100 pages he has published elsewhere. Included is everything from his four New In Chess books (from Russian Silhouettes to The World Champions I Knew).

We would like to share two of these complete stories in separate blog posts.

***

Genrikh Chepukaitis (1935-2004)

Smart Chip

The 1958 Leningrad Blitz Championship was won by Viktor Korchnoi. Second place was shared by Boris Spassky, Mark Taimanov and a first-category player who had beaten all the grandmasters in individual encounters. The name of this first-category player was Genrikh Chepukaitis, a modest master in classical chess but a true grandmaster in blitz.

Born in Leningrad in 1935, Chepukaitis began playing chess at the age of 14. Although he did say that when he was in the army, he studied in Baku under Vladimir Makogonov, and when he returned to Leningrad he sometimes went to lessons by Furman and Borisenko, practice was his real teacher. He confessed: ‘I found mastering all the subtleties boring and I soon gave up these studies. I didn’t get a classical chess education. Blitz was my great and only trainer – I taught myself to find the right squares for my pieces as the seconds ticked away.’

Indeed, blitz became his passion and Chepukaitis spent days, weeks and months playing innumerable games. His results in other tournaments were far more modest, but he had few equals at speed chess.

When he became blitz champion of Leningrad for the first time in 1965, ahead of many titled players, Chepukaitis formally wasn’t even a master. Although he had achieved his master norms, the qualifications commission decided not to award him the title after looking at his games – they found he wasn’t quite ready. When in the following year Chepukaitis decided to play in the Moscow Blitz Championship, they didn’t allow him directly into the final. He arrived on the night train, won the semi-final, spent the night on a bench in the train station, and the next day won a dazzling victory ahead of many famous masters and grandmasters.

In those years he played in Moscow Championships several times, and with success. He particularly proudly recalled the one in which Tigran Petrosian did not take part. The veto came from Petrosian’s wife Rona: ‘You’re the World Champion. Who will praise you if you win? And if you lose? It’s fine if Bronstein, Tal or Korchnoi beats you, but what if you lose to Chepukaitis?’ Tal won that Moscow Championship, Chepukaitis came second ahead of Korchnoi.

The Chigorin Club in his native city remained Chepukaitis’s main and favourite battlefield. He played in the local blitz championship 47 times. Forty-seven times. He won on six occasions, the last time in 2002, when he was already long past 60. If he didn’t happen to get through to the final, he would receive a personal invitation, as a blitz championship of the city without Chepukaitis was inconceivable.

On that day the spectators stood on the tables and window-sills of the club, not only because renowned grandmasters were taking part in the tournament, but because Genrikh Chepukaitis was playing, and he was capable of beating – and did beat! – those same grandmasters, Korchnoi and Spassky, Tal and Taimanov. For him the day was a holiday, his personal holiday, and he appeared in the club clean-shaven, in a snow-white shirt and tie.

On these occasions his colleagues could be seen at the club, workers from the compression section of the optical-mechanical factory, where he worked all his life. It didn’t matter that they barely knew how the chess pieces moved, they couldn’t miss such a spectacle: their Chip had come to smash the grandmasters!

Chip. That’s what everyone called him, and although in his last years he became Genrikh to some, and to young people also Genrikh Mikhailovich, everyone still called him Chip between themselves. Chip wasn’t a professional chess player. All his life until he retired he worked as an electric welder: overalls, safety goggles to protect him from the spray of flying sparks, everything you’d expect. People who knew him in that capacity confirmed that he was a highly-qualified welder. He woke up at five in the morning, if he’d been to bed at all, to get to the factory gates on time, and one could only be amazed that he could keep up this lifestyle: all his evenings, and very often his nights too, were filled with the game.

The game was what he lived for. He played everywhere: in the Chigorin Club, in the clubs of various palaces and houses of culture, and in the summer on the Kirov Islands, in the parks, and in the Holiday Garden. Supporters and admirers always crowded around his games; he liked playing in public and while his opponent was thinking about a move he would exchange a word or two with someone or calmly roll his next cigarette, paying no attention to his alarmingly hanging flag.

He often carried the wooden chess clock, the tool of his trade, around with him in a bag. In the machine gun fire on the clock the last shot always came from him, and sometimes the clock couldn’t take such crazy cannonades and the button would fly off the body of the mechanism. Occasionally, by careless movements the clock was pushed out of place, like an ice hockey goal, pieces and pawns fell over, and instead of an attacking position there would be a chaotic pile of pieces of wood that had rolled all over the board.

I can easily picture him at that time: not very tall, with short, muscular arms, tiny eyes, a cheerful and cunning expression, and black, tousled, slightly curly hair with early touches of grey; almost always looking tired and droopy, in a laundered shirt and a dark, eye-catching jacket. Few people took him seriously – in his name itself there was something nonsensical, frivolous, and funny, like in the chess he played.

He could cheat during a game, but he did it cheerfully and without malice. One of his tricks was to turn opposite-coloured bishops into same-coloured ones in dead-drawn endgames. ‘In this case under no circumstances must one rush’, Chip explained his strategy. ‘After changing the colour of the bishop, I make dozens of pointless moves until my opponent notices the sharp transformation of the position on the board. And only after “guiding” my partner into the new arrangement do I move on to decisive actions.’ If his dumbfounded opponent, having lost all his pawns, resigned in bewilderment, and, trying to reconstruct the course of events, said: ‘Wait, wait, at the beginning, it was...’, Chip, who had been refusing to budge for the sake of appearances, would cheerfully agree and set up the pieces for a new game.

There were numerous formulas for blitz: classical five-minute games, three- and even one-minute games, and various kinds of odds were also given. The most common one that Chepukaitis gave was one minute against five. On more than one occasion I have witnessed him playing with these odds against candidate masters, and they often asked that the 60 seconds of Chip’s time be measured strictly on a stopwatch rather than by estimation on the chess clock – of course, there was no such thing as an electronic clock in those days.

Along with the amount of thinking time there were other important issues that had to be discussed before the start of the game, like which side of the players the chess clock would be on. To the uninitiated this question seems utterly idle. In fact, in a blitz game even the extra seconds it takes to reach a clock that is further away from your hand can make all the difference. Other conditions were also discussed, for example, whether the touch-move rule would be followed or if the move would be considered made only after the button on the clock had been pressed. Often a two- or three-game match would be played, known in the West as a rematch or ‘best of three’. It goes without saying that there was always a bet on the game, but these bets could be completely outrageous, just like the rest of life at that time. At one sitting Chip could lose and win sums that were much higher than his monthly wage.

Once I witnessed a match between Chepukaitis and a candidate master, to whom Chip gave rook odds. In compensation his opponent was supposed to take away his c-pawn, which according to Chepukaitis’s theory had exceptional significance, as the centre could only be undermined with the help of this pawn. His belief in himself was boundless. It was not for nothing that he said: ‘You must be absolutely confident in yourself. When you’re playing a game, you have to be aware of who is the most resourceful at the board. It’s you. You yourself.’

Watching him play, I saw that he didn’t really like positions in which there was one single solution, preferring positions where several continuations were possible. He also played all kinds of card games, as well as dominoes and shmen – a not very difficult game in which the winner is the one who guesses the correct number of a large batch of banknotes in a clenched fist. He could ‘roll’ with any game, any time, with anyone, and people like him were known as ‘rollers’.

In those days the time control in chess left room for meditation, and I sometimes saw Chip in some back room right in the middle of a game, playing cards or ‘reviving himself’ with shmen, while his deeply-thinking opponent was considering whether to place his king’s rook or his queen’s rook on d1.

Sometimes he could be found in the ‘Leninist room’ of the factory among other chess players who worked there. They would take the copies of Pravda and Izvestiya off the table, lock the door, deal the cards or set up the chess pieces, and open a bottle. They were playing under the watchful eye of Lenin, a bust of whom was an essential feature in any ‘Leninist room’.

I recall a typical episode from those days. It was the summer of 1965 and at the Oktyabrskaya Hotel, Chepukaitis and the young Georgian master Roman Dzindzichashvili had decided to play a couple of three-minute games. They started in the afternoon and I left them in the middle of this. When I looked in at the hotel again the following morning, I could already hear the desperate tapping of the clock: the adversaries were still sitting at the table, only from time to time going out to the bathroom to stick their heads under the stream of cold water that was constantly flowing out of the tap. The opening positions appeared on their board with fabulous speed; not surprisingly, as these positions had occurred many times already in the previous games and – experienced blitz players will understand what I mean – they both set them up without much thought, like something that fell into place by itself.

‘Somewhere around five in the morning I was eleven games up, but then Chip got a second wind and not only levelled the scores, but overtook me,’ Dzin said of the struggle, ‘but never mind, it’s not evening yet, now I’m on plus four again.’ An hour later, when I left them alone again, Chepukaitis had caught up...

Roman Dzindzichashvili, himself an outstanding blitz player, recalls that this was far from the only occasion when a single combat lasted so long: ‘Once I played him for fifty hours straight.’ Mark Tseitlin confirms that once he met Chepukaitis on a Friday and played blitz with him for three days in a row: ‘The score went back and forth around plus three on one side or the other and the stake was a rouble per game, but once we’d started playing, we got into it and simply couldn’t stop.’

Chepukaitis talked more than once about his head-to-heads with Mikhail Tal. The very first one took place in Leningrad, in a hotel; the elderly man that Chip met there, and whom he at first mistook for Misha’s uncle, turned out to be Rashid Nezhmetdinov. Chepukaitis beat the master of combinations with a score of 5-2, after which Tal entered the room and got involved. He also played seven games and according to Chip lost almost all of them, although the following day he won a rematch.

True, on each occasion Chepukaitis gave a different score of this successful match, and now it’s difficult to check the absolute accuracy of this story, but I myself witnessed the duels between Chepukaitis and Tal on more than one occasion and I can confirm that each of them won some of the battles. And so it was at the national championship in Kharkov in 1967. Chip would play his regular games at the speed of a hurricane as usual and, after quickly freeing himself, loitered about the hall, waiting for Tal. When Misha finished his game, the blitz began, often with a large crowd of spectators. I can testify that the overall score was about equal and there were no boring games.

Some people create trends in chess and others follow them. Chepukaitis didn’t belong to either of these categories: he had his own opening theory, completely built out of his own games. ‘There are two kinds of openings,’ said Chepukaitis, ‘one that you play well and another that you play badly.’ He himself liked to create an irrational position right from the opening, chaos on the board, which he called a ‘bazaar’.

Chepukaitis’s favourite opening with the bishop coming out to g5 after a first move with the queen’s pawn was founded on his dislike of studying other, more solid openings. This was his favourite strategy: move this bishop out as soon as possible, exchange it immediately and start digging a trench for the other one.

In the artificial world of chess all the pieces were living beings to him, but the knight was his favourite. He admitted more than once, ‘I love knights, without knights chess would just be boring.’ What he didn’t call them – the elite of the fauna on the board, hunchbacks, horses, racehorses, geldings, nags. It wasn’t surprising that when he saw Deep Blue exchanging a bishop for a knight on the fourth move of a game in the New York match with Kasparov in 1997, Chepukaitis was delighted: ‘Finally the computer has begun to understand something about chess!’

Petrosian titled one of his articles ‘An opening to my taste, or why I like the move Bishop g5.’ ‘Petrosian campaigned for moving the bishop out on the third move, while I prefer to do it a move earlier’, Chepukaitis said, lamenting that bringing the kamikaze bishop out to g5 on the first move was forbidden by the rules of the game. He called this thrust by the bishop the ‘mongrel opening’, arguing that other openings have ‘plenty in them that people are sick and tired of.’ The idea of this move was revealed with the greatest effect in a game between Chepukaitis and Taimanov at one of the city blitz championships, when after the moves 1.d4 d5 2.♗g5 his opponent, caught by surprise, played 2...e6. In the same instant the black queen disappeared from the board as if Chepukaitis hadn’t even expected any other move, and the grandmaster, pushing the pieces together, said angrily, ‘You should be selling beer, not playing chess.’

Chepukaitis believed that the thousands or tens of thousands of games he had begun in this way provided enough grounds to name the opening after him. ‘So what if some Trompowsky fellow made this move even before the war, all the ideas in this mongrel opening were worked out by me and me only’, Chepukaitis argued. But no one took his opening seriously in those days, and the part devoted to 2.♗g5 in the article on theory that Boris Gulko wrote after the 1967 tournament in Leningrad, where Chip used this move many times, was ruthlessly cut out by the editor of the magazine.

With the black pieces Chepukaitis played various systems with the fianchettoed dark-squared bishop, but of the openings he created his favourite was the ‘rope-a-dope system’. In this system, where Black deliberately gives up the initiative to his opponent, White loses the benefit of any concrete theoretical recommendations and if he plays routinely, the spring in Black’s position may be released as if all by itself. Depending on his mood he can use this defensive system as White too, directing fire onto himself.

There was clearly thought behind each of his moves and his play was full of original, unconventional ideas. Once, after he had sacrificed his queen for two minor pieces on move five as Black in a game with Zak in the Leningrad variation of the Nimzo-Indian Defence and literally routed him, Zak, after resigning the game, asked Chepukaitis nervously: ‘You were toying with me, of course?’ Years later in the Leningrad Palace of Pioneers Vladimir Grigorievich Zak, one of the trailblazers in this variation, would still analyse the position that had arisen in that game with Chepukaitis with amazement and disbelief.

In one of the rounds of the Leningrad Spartakiad of 1967, I was playing on the board next to Chepukaitis. During his game with Ruban Chip kept going out to the foyer to smoke and talk with friends, coming back to the hall only to quickly make his next move. I think that if he’d had the chance to play in American tournaments, where events with classical, rapid and blitz time-controls are often held at the same time, he would have run from hall to hall, playing a few games simultaneously, as, for example, the British grandmaster Bogdan Lalic does.

‘Did you see the show I put on today?’ I overheard Chepukaitis saying in the lobby after Ruban had resigned.

‘Was it all sound?’ he was asked.

‘Who knows, without a half-litre of vodka there’s no way to tell’, Chip replied with a smile in his favourite way. This fantastic game, which today has been subjected to the merciless verdict of the computer, doesn’t stand the test of accuracy, but it still delights anyone who in chess appreciates more than just logical play in the opening and the exploitation of a small advantage in the endgame.

Once, in a discussion about the constantly shrinking amount of time allocated for thinking, Anatoly Karpov said that we might all end up playing blitz, and then Chepukaitis could become world champion. ‘Yes, he might,’ David Bronstein remarked, ‘and I don’t see anything wrong with that. Genrikh Chepukaitis is a magnificent strategist and a brilliant tactician. His countless victories in blitz tournaments are due to his uncommon skill in creating complicated situations, in which his opponents, who are used to “correct” play, simply get lost.’

Several years before his death Chepukaitis wrote a book on speed chess, blitz, and how to play in time trouble. He formulated the main idea of the book very clearly: ‘There’s absolutely no need to play well, your opponent must play badly!’ He assigned a very important role to the atmosphere created during the game and the role of the adversary: ‘When you begin the game, you have 16 pieces of vastly varying values. But there is one that is much more significant than all the others – the 17th piece. This is your opponent. He is the one you must reckon with when choosing your moves. Above all you mustn’t prevent your opponent from making a choice. I try to present this choice to my partner and I very much hope that he will make the next blunder! He’ll find a way to lose if you don’t get in his way too much. A chess player is only a human being and he was born to make mistakes, to drop pieces and overlook things.’

In his book he wrote about what he considered dead weight in situations when there was limited time for thinking, that, ‘kindness, bashfulness and carefulness are only needed to hide your true intentions. Pushiness, bluffing, adventurousness and shrewdness are essential, though. Being fearful, unsure of oneself, theoretical or panicky is unacceptable. Help your opponent lose his rhythm. Confusion is adequate compensation for a sacrificed piece. An occasional distant, irrelevant move can be a frightening weapon. Your conduct at the beginning of the game should follow a simple rule: clarity in the opening is more important than a material advantage.’

He wasn’t looking for truth in the game, leaving this occupation to super grandmasters and the computers he so disliked; he was seeking only and exclusively his own rightness, called victory. In the search for his own rightness he had a limited number of seconds at his disposal, and I would suggest that an air traffic controller’s reply to psychologists trying to find out what he thinks about in an emergency: ‘There’s no time to think, you have to see’, would be very dear to Chepukaitis’s heart. And if you asked him what truth is in chess, he might reply in the words of a hero in Agatha Christie’s novels: the truth is whatever upsets someone’s plans.

Another essential piece of advice concerned the clock: ‘Make your moves closer to the button on the clock. This is very important! Remember: your hands must be quicker than your thoughts. Don’t move where you’re looking and don’t look where you’re moving. This is a chance! If your opponent has forgotten to press the clock, make an intelligent face, as if you’re thinking. As your opponent’s clock is running, you’re getting closer to victory. When you reach the endgame, make random moves, following the only rule: all your moves must be as close as possible to the button on the clock. Never forget Chepukaitis’s button theory.’

Chepukaitis confessed that he had never managed to patch up serious gaps in the opening and endgame, only to camouflage these gaps. ‘I don’t understand serious chess and I consider myself hopeless as a serious chess player’, he said more than once. This, of course, is an exaggeration, but indeed, the difference between Chepukaitis’s results at blitz and in normal chess tournaments was striking – his rating never exceeded the modest 2420 mark. It is remarkable that for someone with the kind of talent that Chepukaitis had, time for plunging into contemplation was a negative force, leading to doubt, self-analysis and mistakes. This is a well-known paradox, characteristic of those who play by their animal instinct and their gut feeling: hesitation and doubt creep into the thought process, natural talent deserts them, and their play loses its originality.

Curiously, at the beginning of the seventies, when the curve of his tournament successes was climbing higher, his blitz results deteriorated. He admitted at the time: ‘Before, I didn’t understand anything and wasn’t afraid, but now I know that you must not play this way and you mustn’t play that way...’ Moreover, he resolutely scorned any sensible lifestyle – he could arrive three-quarters of an hour late to a game, start the round after a sleepless night, and he never let go of his cigarette. But, like other people with such nervous systems, his body had a defence mechanism: he could switch off, even just for a few minutes, wherever he liked – in an underground train, on a park bench, or in an armchair in the foyer of the chess club.

Although by profession he was a worker, an electric welder, in reality he was, of course, a chess player, and games are the main part of a chess player’s life. Original plans and amazing combinations sometimes sprouted from the scrap heaps of Chepukaitis’s games. In his life he played hundreds of thousands of games, and almost all of them have sunk into oblivion, like the painting of an artist who, to avoid having to spend money on an expensive canvas, paints a new picture on top of an old one. Chepukaitis himself didn’t worry much about preserving them, just like the Hungarian tycoon who went to a ball in boots embroidered with pearls that were fastened on so carelessly that they fell off during a waltz.

Chepukaitis was a man with a restless and original mind, utterly lacking the capacity for reflection and constantly active. He knew an extraordinary number of tall tales, anecdotes and yarns, and the truth in them was mixed with fiction, so it was for good reason that he admitted taking quite a bit from Baron Munchausen’s stories for his own. He often repeated the stories, and after a quarter of an hour he would become tedious to listen to, but out of politeness no one interrupted him.

He wrote verse, terribly long poems, excerpts from which he would read to anyone who wished to listen. Although there were funny as well as sad lines in these poems, they were the typical work of a rhymester. While reading he made abundant use of mimicry and helped himself along with his intonations – it was obvious that this activity brought him pleasure. The poems were about chess, about his favourite piece on the chess board – the knight – about the ‘mongrel opening’, and about the grandmaster title, but most of all they were about him. Just as he was modest in his assessment of his abilities at serious chess, so he zealously guarded his reputation as a blitz player. Sometimes he spoke and wrote about himself in the third person, calling himself ‘the legendary Chepukaitis’; but the most common word in his poems was ‘I’.

To a psychologist, this need for self-affirmation and for proving his own superiority would probably be clear evidence of compensation for non-recognition of his contributions as an individual, real or imagined. After all, central to the game is the hunger to surpass others, to become the winner and in that role to receive honours. Although he achieved international master norms several times, and once he was close to becoming a grandmaster, he never received the official title, which is so faded, ground down and devalued today, and he felt hurt and passed over. This sense of grievance, a grievance for the non-recognition of his talent, is discernible in the last line of his book, printed in bold letters: Master of sport of the USSR Genrikh Chepukaitis.

It was also discernible in the inscription on the copy of the book he gave me: to a friend and grandmaster. And in a quatrain of one of his poems:

They haven’t yet made me grandmaster

Maybe after I die;

Into the Guinness Book of Records

I’ll make my way up high.

You can imagine how sweet it was for him to see on the tournament table for the Senior World Championship in Germany: GM Chepukaitis, when the organizers mistook the initials of Genrikh Mikhailovich for a title.

One of the humorous maxims that Chepukaitis’s book is full of reads: ‘I have noticed that men always marry the wrong women, and it’s the same at the chess board – you make the wrong move – mistakes are unavoidable!’ Chip knew what he was talking about. He was married five times, but this number should not be incorrectly interpreted: in fact he was very shy and susceptible, and when he fell in love, he always suggested making it ‘legal’. But in life, as in chess, he was frivolous – when he and his second wife decided to split up, they simply threw away their registration certificates. When he was preparing his third marriage it came out that the previous one hadn’t been dissolved and he was very nearly put on trial for bigamy. His last wife, Tanya Lungu, a chess player from Chisinau, was 33 years younger than him. His book is called Sprint on the Chess Board. In actual fact his whole life was a sprint, and he didn’t pay much attention to false starts.

He admitted that he was a bad father to his two children, but when a boy whose surname was Chepukaitis came to the chess group at the Anichkov Palace a few years ago, confirming that he was the grandson of the famous Chepukaitis, the grandfather was indescribably proud when he heard about it.

When the walls around the national fortress came tumbling down, he travelled abroad several times, playing in Senior World Championships in Europe. Many of the people with whom he had spent long years at the chess and card tables left for Israel, Germany and America. For a while he, too, thought about using his Jewish ancestry to emigrate to Germany. Chepukaitis was his mother’s surname and in the ethnicity section on her passport she was described as a Pole.

Those who knew her recalled a woman with a characteristic face, an aquiline nose and curly, grey, formerly black hair. Genrikh Mikhailovich was also designated a Pole in his passport. The papers of his father, Mikhail Yefimovich Pikus, a Jew who had worked as a foreman in the Kirov factory before the war and perished at Stalingrad in 1942, have been preserved. But the marriage of Chepukaitis’s parents wasn’t registered, so there was no way he could prove anything 60 years later, and the idea of emigrating gradually melted away.

He had numerous acquaintances, chess and card players, blitz partners, drinking buddies, those who knew him simply as Chip, but he didn’t have any close friends. In company he told his funny stories incessantly and for the better part of his life he had his favourite, well-worn records. Even as a young man he had had a tendency towards long monologues, and as the years passed he became even more verbose. An endless stream of words flowed out of him, and socializing with him wasn’t easy; actually, he needed a listener more than he needed a conversation partner. There was chess in his flood of words, but mainly there was him, he himself, the untitled and unrecognized, who in fact was great and legendary.

The reaction came later. His wife Tanya recalls that their home life was already suffering. He was immersed in his own world, in his thoughts, and he was often withdrawn and taciturn. With him – so unpretentious in his food and clothes – domestic life wasn’t easy: he demanded constant attention, because he was genuinely focused only on himself. He read everything he could get his hands on, mainly contenting himself with light stuff – newspapers and glossy magazines, the flow of information that catches the eye but doesn’t detain you, draining away without any consequences for the soul. But if he happened on them, he would also read history books, literary fiction and thrillers. He never owned any chess books himself, but after his wife moved to Petersburg he read her chess books with interest.

In his later years he got a computer and played endless blitz games all night long, usually under the handle SmartChip. Visitors to the Internet Chess Club can confirm that late in the evening, before they turned off their computers, they saw SmartChip online, and if they turned on their computers in the morning, they noticed that Chip was still playing. Although here, too, he often beat well-known grandmasters, and his rating, as a rule, was over 3000, his Internet results weren’t as good as his normal blitz results. It wasn’t surprising: he first used a computer when he was already getting on for 60, and instead of the usual button on the clock his finger had to press a strange thing called a mouse.

In the last few years he gave lessons at Khalifman’s chess school on St. Petersburg’s Fontanka Canal. In person and via the Internet. When pupils arrived from abroad, he used an interpreter, as Chip understandably didn’t know any foreign languages. These lessons were distinctive – he almost always demonstrated his own won games and combinations. A stream of ideas flowed out of him, but he didn’t insist on their strict execution – if those ideas don’t suit you, I have plenty more, he would have said.

Of course, Chepukaitis couldn’t explain the subtleties of modern opening set-ups, but he infected his listeners with his enthusiasm and love for the game, showing them completely different aspects of chess that they hadn’t seen before. He impressed on each of them one of the fundamental postulates of his theory: ‘everyone makes mistakes, grandmasters and world champions, and there is no particular trick to this game. As you gradually acquire experience, knowledge and skill, you’ll be surprised to find that you have talent. Everyone has talent, the question is only how to extract it and demonstrate it.’

He had admirers who saw something in his games that distinguished them from the many thousands of games played every day in tournaments and on the Internet. The Mexican master Raul Ocampo Vargas wrote an article after his death titled ‘Peculiar chess’, and Gerard Welling from Holland even put together a small book with a selection of his games. ‘I’m not sure if I have increased my mastery of the game, but I’m already more confident’, was the first comment of a grateful pupil, which he received from far-off Argentina.

Chepukaitis’s split with his wife in November 2003 hit him hard; they had been together for almost thirteen years. After the divorce and her departure overseas, he was back on his own in his small, neglected one-room flat. This dwelling was more like a bivouac, which he used only for sleeping, and once a week his ex-wife’s sisters would stop by to do housework for the single man: some laundry, and they would fill up the empty fridge as he didn’t buy anything for himself. He needed little, and even out of that little he only needed the tiniest portion. He was flagging somehow, he had completely stopped paying attention to his appearance, spending almost every night in fierce card battles.

In cards, of course, there have always been dirty players, but in recent years they had become even more ruthless: starting from the first day a large amount of interest accumulated on unpaid debts and you could never know what might happen if the debt wasn’t paid for a long period. For them he was a ‘soft touch’, a ‘client’, and they cheated him more than once. But even when he understood who was sitting opposite him at the card table, he still continued playing, believing that in spite of all their tricks and devices, his quick calculations and sharp wits would lead him to a happy outcome of the intellectual struggle. Alas, these were only illusions, and sometimes his opponents at cards, considering him a simpleton, practically laughed in his face.

A few years ago at his wife’s insistence he went to hospital and he was diagnosed as being at risk of a heart attack, and prescribed peace and rest. It goes without saying that he totally disregarded this advice.

Right up to the end he continued playing various card games, and in his last years he put his meagre pension into slot machines almost on the day he received it. His earnings from lessons and blitz tournaments were also swallowed up that way. Games were everything to him, and for those who have never been susceptible to this passion, or, if you like, delusion or disease, it is difficult to understand such a person. He played blitz every day. Of course, he started to tire more quickly in his old age, his reactions got slower, but he never even dreamt of giving up chess.

Until his very last days he visited the chess club in Petrogradsky District, where he regularly played in blitz tournaments with entry fees, often winning them. His standard odds in a game with a master were three minutes against five. This was for players with a rating of around 2400. With candidate masters it was two minutes. He also continued playing in regular tournaments. The recent innovation of a faster time control with an increment after each move appealed to him: as before he played very fast, and his opponent might find himself nervously looking at the clock, on the verge of time-trouble, while Chepukaitis didn’t have much less time than he’d had at the beginning of the game. But he did not like computers, calling them ‘slow-witted personalities’, believing that with the arrival of computers in the game, bluff and risk had disappeared, and everyone had started playing the way they were advised to by the machine.

After he had passed 60 he had a second wind and was successful in several tournaments, in one of them coming very close to the grandmaster title. In 2000 he took part in the city championship, playing against young but experienced professionals. Although he was the oldest player in the tournament, and the only one who didn’t have an international title, Chepukaitis achieved a respectable result in the event, finishing on 50 percent. He was 65 years old, an honourable pensionable age, but looking at him, you’d think there was a mistake in the calendar judging by his spirit: up until he died, no one took him for an old man at all. The generations passed, he played with people who were born at the very beginning of the last century and with those who came into the world in the eighties, who were the same age as his grandson. His lifestyle didn’t change at all – what he had done at 20 he was still doing half a century later, and his old age wasn’t that different from his youth.

Till the end he retained his boyish perception of life. In Leningrad and Petersburg he was more an idea, a symbol, and although he entrusted his thoughts about chess and some of his games to the pages of his book and his lectures on the website, he remains in our memory more as a phenomenon or a spirit. Like a myth that appeared in chess in the second half of the 20th century and flew away at the beginning of the following one.

He died of a heart attack in the night of the fifth to the sixth of September 2004 in Palanga, Lithuania, where he was playing in the last tournament of his life. The last time I saw him was two months before his death in Petersburg. Chip was playing on the stage of the Chigorin Club in exactly the same place where I had played him in the city championship almost forty years earlier. It was the only game I lost in that tournament. He noticed me and we went out to the foyer. Chip had put on a lot of weight, he was heavy, the ‘pepper’ in his hair had almost completely given way to the ‘salt’, and his receding hairline had climbed further back, but still he looked younger than his years. Pleased that one of his fans in Holland was dreaming of taking lessons from him, he began looking for a pen, then a scrap of paper, to write down the address. Striking a light, he smoked a cigarette.

‘Listen, I’ve written a new poem, do you want to hear it?’ he asked, and without waiting for a reply, he began declaiming the rhyming lines of his latest production.

‘Your move, Chip’, someone said, passing by. Not even turning around, he continued reading enthusiastically as the minutes on his clock ticked away. After all he had so many minutes left on his clock that he could have completed at least a dozen games before his flag would fall.