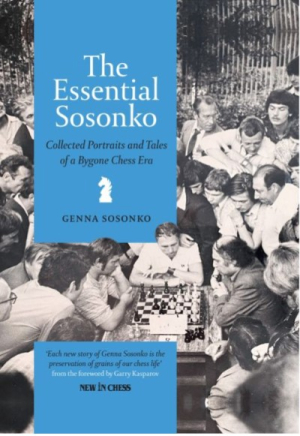

The Essential Sosonko - The heart of a soothsayer

'Each new story of Genna Sosonko is the preservation of grains of our chess life', says Garry Kasparov in the foreword.

We proudly present a one-volume collection of Genna Sosonko's best stories - essential reading for every chess fan interested in the history of chess and the heart and soul of chess players.

No other writer can tell you more about legends such as Mikhail Tal, Viktor Korchnoi, and David Bronstein or unforgettable personalities such as 'Chip' Chepukaitis and Sergey Nikolaev.

This monumental book is a collection of the portraits and profiles Sosonko wrote for New in Chess, plus 100 pages he has published elsewhere. Included is everything from his four New In Chess books (from Russian Silhouettes to The World Champions I Knew).

We would like to share two of these complete stories in separate blog posts.

***

Sergey Nikolaev (1961-2007)

The heart of a soothsayer

In the reputable British newspapers you can find extensive obituaries of completely unknown people almost every day. They are interesting only for being unusual, different from others, sometimes even eccentric. Although the stories about these people are printed on the funeral announcement pages, death is somewhere far away from them, and there is no mood of mourning at all. Why write words of grief and sadness when they were such exceptional people? These are almost entertaining articles with the mood – see what personalities lived among us. Surprising, quirky, original.

Sergey Nikolaevich Nikolaev was one such person. He died in Moscow in 2007, the victim of a rampaging gang of young neo-Nazis who killed him because he didn’t look Russian enough. All his life he was treated as a stranger in his own country, but he overcame that to flourish as one of post-Communist Russia’s first businessmen, and he never seriously considered leaving, although he was acutely aware of the dangers.

He was born in Yakutsk in 1961. The territory of the republic is gigantic, its population is about a million. The climate and terrain are as harsh as can be. The lifespan is the lowest in Russia, with high levels of unemployment and alcoholism. In the Soviet era there were restaurants in Yakutsk that didn’t allow Yakuts in, and on public transport a person speaking Yakut might hear, ‘Hey, you scum! Speak a civilized language!’

Seryezha didn’t speak Yakut, at home they always spoke only Russian. They lived in an earth house next to a cemetery. When he grew up he joked, I was born in a cemetery.

There were five brothers in his family, and he was the youngest. One of the brothers was a policeman, and Seryezha remembered his stories from his childhood – how they beat a confession out of someone, how they forced someone to sign a statement. Or how they put a man in prison and forgot about him, and that man’s still in prison and no one knows how long he’ll be there for. All these stories impressed themselves on his consciousness, and back then he already knew that you could do anything to a person.

He said that he was of shamanic, heathen descent, and something of that had been passed on to him. As the youngest, from childhood he managed the family budget, he knew the value of money, calculating everything down to the last kopeck. As a grown-up accomplished man he said of chess players, ‘Some of them stay babies until they retire, but I, I was already an old man by the age of seven...’

Chess was played in his family. His father played, his brothers played. One is still a chess coach today. When they brought 64 home, the brothers fought over the magazine, and the youngest got it last. Sometimes little Seryezha would go outside in temperatures of minus-50 and wait for the postman so that he’d be the first to get news from another world – the magical text with chess pieces on diagrams.

He studied in a group and at 12 he reached the first category. In summer 1976, when Karpov came to Yakutsk, he beat the world champion in a simultaneous display. Commotion: photographs, journalists. The radio: say a few words. The boy startled everyone – he remained completely calm, even indifferent. Even then he could keep his emotions under control. He became a candidate master. He graduated from school. He went to Leningrad to enroll in a higher educational institute.

People who knew him in those days speak of a young, sociable man, friendly and companionable. They recall walks on Nevsky Prospekt, Vasilievsky Island and the Petrograd district. And endless conversations, conversations; since in those days time wasn’t yet money. He constantly played in Petersburg tournaments. He strove for perfection. But he wasn’t a fanatic, he said that chess was very complex, that he got very tired from working so hard at it.

After graduating from the commerce institute he returned to Yakutia. The young specialist became deputy head of a department in the republic’s Ministry of Trade. He continued playing and became a master. In ’84 he won the national Spartak championship, a strong master tournament. He was champion of Yakutia three times. The republic’s team, for which he invariably played top board, placed highly in Russian events. He said, ‘Don’t think, this match is important, I have to win no matter what. Imagine that you’re playing in an individual tournament. Don’t worry about the others, each of you plays your own game.’

Both old and young listened to him.

Perestroika was dawning. When the opportunity to leave the country appeared, Nikolaev was one of the first people to start playing in foreign opens. In Harkany, Hungary, he became an International Master, winning the tournament and overfulfilling the norm by a point and a half. If he was on form, he could even beat a decent grandmaster, but if he wasn’t playing well, he’d drop to a minus score, and sometimes a very low one. He was incredibly cunning at the board, he knew what to play and against whom. In the chess world they called him Cunning Nikolasha or Nikolaev the Yakut.

He said, you have to have a feel for things, is it your day, and if you have a gut instinct, follow it, play to the end! He gave Ivanchuk as an example – if he doesn’t have this feeling, he quickly wraps up the game, and in that case it doesn’t matter which colour he’s playing.

Even then Nikolaev concerned himself with issues that weren’t only to do with chess. His colleagues recall that much of what Sergey said back then seemed unbelievable to them. He might say to a master who had arrived at a foreign open from some remote Russian town, ‘You idiot, soon everything will disappear from the shops, buy potatoes, flour, why are you blathering on to me about fancy stuff like ratings, aren’t you worried about your children? Your family? What are you thinking, it’ll always be like this? There won’t be any more cheap plane tickets soon, life won’t just get more expensive, it’ll get much more expensive. Only those who play at the very highest level can live off chess...’ They exchanged glances: ‘What’s the Yakut going on about, it’s complete gibberish’, but then suddenly they were convinced – ‘he’s exactly right! Everything that Sergey said came to pass...’

In January 1990 during the traditional festival at Wijk aan Zee a short young man with slanted eyes and broad cheekbones came up to me and humbly introduced himself: ‘Sergey Nikolaev.’ A few years later we met again, this time in Amsterdam. We saw each other in Moscow a few times, then we met in Holland again.

Sergey had his own opinion about everything and fiercely defended that opinion. Sometimes what he was talking about inspired disbelief or even a sneer. Often the people he was talking to would exchange meaningful glances when he expounded his ideas. I confess that I had similar thoughts, too. I seldom agreed with him, and some things I would reject or even oppose strongly, but being with him was never boring for me.

He felt confined within the boundaries of that system – his mind was always going over the most varied combinations: how to exchange a flat? How to get a grant in Yakutia? How to get a permit to live in Moscow? How to see the necessary people? And he could intertwine the most complicated multiple-move variations, calculating them in the conditions of that phantasmagoric government.

When he got the opportunity, he decided to try doing something himself. He started with chess, organizing a tournament in Podolsk, near Moscow. The year 1991 was approaching, the Soviet Union was entering the last months of its existence, and everything was in short supply in the country, but Nikolaev anticipated every detail. One of the club’s employees served tea and coffee in the canteen, someone supplied pastries from God knows where, and someone else provided rolls of toilet paper.

He played in Podolsk, too. Trying to combine playing and everyday worries, his game collapsed. But the tournament worked, and Nikolaev decided to continue his chess projects. He thought up some kind of state chess programme in Yakutia, a chess textbook for the northern peoples, and started attracting grandmasters and masters to this project. He wanted to put chess on television.

It didn’t work out. Sergey realized then that if he stayed in chess, he’d always be dependent on sponsors, high-ranking bosses, events beyond his control. Moreover, having passed 30, he clearly recognized that he himself couldn’t make it in professional chess, that his time had passed.

‘When you’re young,’ he said, ‘you often get excellent results, but these are only advances, and those advances have to be repaid later. Your results must improve. If that doesn’t happen, if you hang around in one place, the smartest thing is to leave.’ Nikolaev left chess.

He still had some of his connections from the old days, he got loans on favourable terms, went into the market and established a private company. He worked incredibly hard. Worked and studied. He studied everything by himself, he was what’s called a self-made man. He didn’t sleep much. He completely gave up chess then, not even having a set at home. But he snatched time to read the periodicals, trying to stay in touch with events in a world that he’d been part of for many years.

Choosing the direction of his business, he settled on the most neutral, even at first glance funny one: buttons. But his aim was also distant: ‘As long as the world turns,’ he said, ‘a woman will always wear clothes, and buttons will always be needed.’

In Moscow he started with underground pedestrian crossings to metro stations. He hired girls, brought them buttons himself in huge sacks, and the girls sold them one by one. Well, he wasn’t the only one who started like that back then. Some sold buttons in the crossings to Moscow metro stations, others, like Abramovich, for example, children’s toys. Nikolaev knew, of course, that other spheres existed, where profits were incomparable with the button business, but making a profit in those spheres came with an enormous risk. The risk of losing not only your business, but your life, too. And for every dozen people who made a success of it, a multitude had to bow out, back off, make themselves scarce. But he stuck with his buttons, threads and accessories. He stuck with it and became one of the biggest suppliers of these products in the country. The sole boss of the leading companies on the Russian market.

He spent a good two decades in chess, he knew that world like nobody else, so it wasn’t surprising that it was mostly chess players who worked for his company. The guys who started with Nikolaev got called ‘button men’, but that hardly bothered them. Besides, there wasn’t enough time to pay attention to things like that: they had to work at full throttle. He enjoyed absolute authority in the company, and they respectfully called him Papa.

The company was formed primarily according to Japanese principles. If he gave someone a job, this was like a lifetime hire. Of course, the guys didn’t sing the company anthem when they arrived at the office, but everyone who worked for Sergey had to be absolutely loyal to the company, to live for its interests much more than they would somewhere else, where, closing the door behind him at six in the evening, the employee forgets about everything until the next morning.

Nikolaev worked without any timetables or schedules, a nine-to-five job wasn’t for him. He ridiculed schemes, business plans and timetables for development. Paperwork didn’t exist for him. Adding up expenses after a trip, keeping the tickets and the hotel bill – he wasn’t interested in any of that. A person would spend however much they considered necessary, then give a personal report to him about their expenses, and the case was closed.

International master Igor Belov, who worked with Sergey from the very first days, recalls, ‘He generated ideas, constantly generated ideas, often so brilliant that they bordered on genius. At work that’s what he was often called – the Genius. But I have to admit, far from all of these ideas were wonderful. I’d say that out of 10 he suggested, five were a long way from reality, sometimes even absurd, four were excellent, but one – one was genius!’

His business acumen was unbelievable. This wasn’t just the view of an experienced sailor, able to predict the weather from the signs, no, this was some other kind of feeling. What to call it? A gift? A talent? Natural intuition? You couldn’t help thinking about his shamanic roots. When he was asked how he was able to see everything, he only smiled his enigmatic smile: ‘I have the heart of a soothsayer.’

He could read people’s faces brilliantly. A completely respectable, apparently well-off gentleman would come in. It was enough for Sergey to chat with him for quarter of an hour: ‘The client is empty like a drum, he’s making plans, but they won’t come to anything, only noise and dust.’ Then someone completely ordinary-looking, drab, even, would suddenly show up, who couldn’t string two words together. Sergey hardly glanced at him: ‘We should give him what he’s asking for.’ He also trained his employees how to look people over, to assess them, but can you really teach that?

Reading books by wealthy people about how they successfully lived their lives, how they managed everything, he was always interested in how they had made their first money, harrumphing: ‘There are only three things you can earn honestly – calluses, hernias and debts. I’d also like to know, where did the firewood come from? It’s a small detail, of course, but they keep it quiet. Where did it come from?’

From childhood he counted only on his own strengths, and his self-confidence was limitless. He had the gift of persuasion, saying, ‘I can justify any point of view. Anything.’ Business demands tenacity, daring, a lack of sentimentality, and even cruelty. The successful businessman Sergey Nikolaevich Nikolaev possessed all these qualities. Under an external softness and nonchalance was hidden a colossal strength of will and an iron grip. A person talking to him couldn’t read anything on his benign face. He himself had a very good feeling for that person, understanding his intentions on the fly, drawing conclusions for himself and directing negotiations in his own favour. Coming into contact with him, people probably went away with a pleasant feeling of their own intellectual superiority. And they were mistaken about that in the worst possible way.

When he moved to Moscow for good he said there was no way he’d go back to Yakutia, that being there depressed him. Lacking his charisma and his talents, Sergey’s brothers were nothing like him. Also, they couldn’t avoid the ailment that is very widespread in those regions with terrible cold temperatures, an extremely harsh climate: an irresistible desire for alcohol. He only felt an affinity for his niece, remaining friendly with her and buying her a flat in Moscow and presents.

He didn’t refuse himself anything. Fruit, vegetables – at any time of year, he got everything fresh. Juices – natural. Mineral water – only the French Evian, he thought it was particularly beneficial. In recent years he occasionally allowed himself a glass or two of red wine, but it had to be only the best. The best. He never drank tap water, buying and drinking only purified water. He washed his dishes in a special solution, not trusting the washing-up liquids that were sold in the shops – he thought they left traces on the dishes.

At first he avoided having a computer because he thought they gave off radiation. True, he gradually got used to them, then learned to use them, but on an amateur level, mainly surfing the web, gathering information and following news on the chess front.

He disliked animals, tried to steer clear of them, believing they carried diseases. He thought that microbes were teeming everywhere, so he wore gloves. He was obsessed with health, medicine and correct nutrition, and sometimes this took exaggerated, grotesque forms.

All his friends were chess players. When they came to Moscow he always invited them to a restaurant. Usually they went to his favourites – an Armenian one or an Uzbek one. There he felt at home, advising people to try some dish or other, as in, ‘Believe me, Genna, the salads here are heavenly...’ Despite the fact that there might have been a dozen of the most varied kinds on the menu, he made his specific, finding out from the waiter exactly which country the artichoke was from, and whether the mushrooms were really wild, as the menu stated.

Once we ate in the restaurant at the St. Daniel Monastery. Here, again, there was an element of show for the newly-invited, of course: the monastery atmosphere worked – monks, icons on the walls, silence. He immediately let me know that he was a frequent guest here, too. I can confirm it – he didn’t even open the menu. He knew without looking at it: ‘I recommend the baked carp, their fish is straight from their own ponds, it’s superb.’

Although he said, ‘Personal life is the most important thing. All the rest is crap. Personal life comes first’, he himself wasn’t married. His attitude towards women was generally rather sceptical, wary, and also he didn’t want to let anyone get too close to him. He believed that having another person with him constantly would restrict him, that the minuses outweighed the pluses. He thought that with his health and illnesses, sooner or later he’d end up in a wheelchair, and he didn’t want to be a burden on anyone. And in general he thought that he wouldn’t live long.

Like other kinds of love, love for chess comes in all forms. Sergey Nikolaev was interested less in the process of playing itself than in the nature of success, the psychology of single combat, and in later years also the role of chess in the enormous free market where everything is bought and sold.

He never talked specifically about variations, combinations or new ideas in the opening. He cared about something else – the environment around chess, the people in chess. He liked to recall the people he knew, he wondered how X’s life was going, how Z was doing, were they still in chess, and if not, where were they? Sometimes he asked about people who had disappeared from the public arena almost a quarter of a century before, talking about them as if he’d seen them yesterday.

He called his former colleagues, scattered around the cities and villages of the huge country, and he called old acquaintances who lived outside Russia. They recall that Sergey, starting a long, long conversation, could sometimes overstep a boundary, becoming tiresome and even annoying, without noticing this himself.

He told me once, ‘In the West everything is more complicated for you, but at the same time it’s also simpler, because it’s more transparent. Here, though, the rules of the game are different.’ Sometimes he himself started thinking about moving to the West, but more in an abstract way. We can only guess what Sergey Nikolaev would have become outside Russia with his talents and charisma, and I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that here, too, he could have achieved success. But where would he have found people with whom he had something in common, whose company he enjoyed, with whom he was comfortable? People to talk to, people who would listen to him?

A year before his death he wrote a long article with figures, tables and charts. It was called ‘The economics of Russian chess. A chronicle of collapse.’ In this article he didn’t suggest trying to save his drowning homeland: he realized that the phenomenon of Soviet chess was impossible to replicate. He just thought that in the new conditions the number of professionals should be reduced to a proportion that he considered rational: ‘We at least need to empirically determine how many grandmasters and masters are necessary in market conditions. Is it worth spending money preparing grandmasters for future unemployment?’ He deliberately avoided even the phrase ‘chess professional’, explaining: ‘the reality of the past few years has eliminated the economic meaning of this term.’

He wrote that ‘the need to express myself has arisen after a conversation with male and female friends who continue to play in tournaments, because some of them have been thinking about ending their careers for years already, but they don’t have the strength to do it.’ Acknowledging that his article wasn’t a scientific work, just the everyday musings of a person who liked chess, he worried: ‘Will they get it, will it offend anyone, and is the article really needed at all?’

The article evoked numerous positive responses. He read these responses with close attention, and I know that he himself asked some people to write a response. Despite his apparent indifference to the reaction of those around him, he was extremely hungry for fame, and the opinion of others and recognition were in fact very important to him.

He might say to a young chess player, ‘Have you thought about the future? Look at the veterans playing in tournaments, they’re like lamp-posts in the street, every passing dog tries to lift its leg on them! And don’t complain later that you’ve wasted your time, that I didn’t warn you or you didn’t know...’

When he heard young people start boasting about their victories over fading stars, he always interrupted: ‘It’s not Portisch you’ve beaten, you’ve beaten his namesake. When Portisch was playing chess, you could never even have been paired against him, and you say you’ve beaten Portisch.’ Another time someone said in his presence that he’d easily beaten Romanishin. ‘Romanishin, you say? Do you know how Oleg Romanishin played, what a fantastic grandmaster he was? You’ve played a pale shadow of him, a namesake, and now you’re boasting here...’

That’s why, probably, when someone recalled in front of him how he’d once beaten Tal in a blitz game, he always broke in with: ‘Was that really the Tal of the sixties? Misha was already half dead.’

He assured young people that the risk was too great, that if it didn’t work out, there would be problems, and not enough time to solve them. ‘Conditions, you say? A hotel bed and sandwiches, those are the conditions you’ll get! Give up this rubbish’, Nikolaev said to his friend Sergey Shipov, when he decided to continue his chess career after graduating from the maths and physics faculty of Moscow State University.

Shipov became a grandmaster, attained a respectable rating, was Kasparov’s sparring partner and everything apparently turned out well. But when Nikolaev inquired once about the life of a professional, Shipov replied, ‘Oh, you were right, Sergey, it’s all coffee and sandwiches.’ Nikolaev only pursed his lips: ‘When he should have been playing chess, he was doing maths, and when he should have been doing business, he went off into chess...’

Nikolaev said, ‘I’ve weaned myself off chess.’ He claimed that a chess dependency is more destructive than many others; he thought that ‘weaning’ women off this dependency was a virtually hopeless task, and with men it was also difficult, but here there were gradations. ‘Chess is a kind of disability’, he repeated. ‘You can still do something with candidate masters, you can train them for a normal profession, candidate masters are at the third level of disability. Masters are at the second level, here it’s already more difficult, you need to take an individual approach, it’s a lot of work. Grandmasters are in the first class of disabilities! For grandmasters it’s too late to work, this is a hopeless case. There are exceptions, of course, but they’re few and far between...’

Another time we referred to the Three Tenors, who were on a world tour at the time, receiving millions for a concert, while the musicians in the orchestras that accompanied them were happy with a few hundred dollars and didn’t complain about their lot. ‘That’s what I’m talking about, and isn’t chess just the same?’ Sergey interrupted me. ‘A few tenors, and the rest? The musicians will sit like that in the orchestra until they start collecting their pensions.’

I said that it was impossible to make a movie without wasting a huge amount of film and impossible to write something worthwhile without crossing out any text. It’s the same with chess, to reach the summit, or even the foothills, you need time, as not everyone was born a Fischer, a Kasparov or a Carlsen. That in most cases the chess player moves forward jerkily, like the hands on a station clock, and he proposed that at almost the first lag of the minute hand you should start thinking about whether the mechanism is broken.

He insisted that after a couple of unsuccessful tournaments you should seriously start thinking about whether to continue your career, otherwise you’ll get sucked into playing and there’ll be no way back. And the decision must be taken as early as possible: if there are no results in early youth, you should give it some distance, switch to something else.

I tried to object, citing freedom, the absence of a boss and routine nine-to-five work, before which you still have to get there and then back home – you blink, and the day’s gone by, you don’t notice that your whole life is passing that way, while here you’re a free agent, plus there’s travel, you see the world...

‘Travel?’ Seryezha didn’t agree. ‘But what if you’re long past 20 and you’ve already seen the world, and what kind of world anyway? The walls of a third-rate hotel and a tournament hall, or do you think, Genna, that the players in open tournaments go on tourist excursions around the city before a round?’

I recalled the American grandmaster Kenneth Rogoff, whom I played in an Interzonal back in 1976. Leaving the game, Ken graduated from Yale University, became one of the world’s leading economists, Chief Economist of the International Monetary Fund. In an interview a few years ago Rogoff said, ‘Being a chess player is much more like being an artist. It’s a bohemian life,’ and added with a sigh, ‘and I could have gone that way.’

Sergey was prepared for this try: ‘He said that because he’s financially independent now. He’s also not young any more, which is why his youth seems rose-coloured.’ And he again repeated that the market was saturated, that life is short, and youth even more so.

I can’t say that all our conversations were arguments, really they were discussions about the problems of chess, about its future. He lamented that little was written about the fact that chess players never get Alzheimer’s disease: ‘And why’s that?’ Sergey said, ‘Chess constantly gives the brain work to do; it’s a shame that no research has even been done on this subject, I’m sure the results would have shown that chess is useful.’

He liked that in Dublin Alexander Baburin wasn’t coaching but was doing educational work, teaching children at a school. ‘Chess should definitely go into the educational sphere’, Sergey said. ‘The children will be happy – it’s an interesting, fascinating game – and the parents, too – it’s good for the child’s intellectual development, plus chess professionals in the role of teachers will earn a solid crust of bread.’

He was speaking ironically when he defined chess players’ disability levels, but at the very end it turned out that he had the disability himself – he didn’t get away from chess. After all, he’d said many times that if you get hooked on chess in childhood, you rarely let go of the wooden pieces. He didn’t let go of them either – he returned to chess. In another capacity, but he nevertheless returned. Unlike Maecenas, who lived 2000 years ago, he wasn’t born a rich man, but Nikolaev became a Maecenas. An advisor, a friend and a patron of many chess players. And not only chess players.

International master Roman Skomorokhin, who was living in Nizhny Novgorod, started working for his company in 1997. He recalls, ‘If I happened to be in Moscow, I always met up with Sergey, of course. When we went into a shop and I was buying something, Papa wouldn’t even let me get my wallet out. He always paid for the purchase himself, literally forcing me to get another pair of shoes, or another two or three shirts. “Take it,” he’d say, “Roman, take it, it suits you.” And it was exactly the same with everything. And if he promised something, he never forgot about it. This quality is very rare nowadays, very. Papa never forgot anything...’

He acquired kit and accessories and paid to rent the pitch for the company’s employees, who enthusiastically kicked a football around every Wednesday. He didn’t go to these matches himself, but he thought that if the guys liked it, if it put them in a good mood, then it was also helpful for the business...

Igor Belov: ‘He did good deeds just because, good deeds for their own sake. You want to change your car – what kind do you want? To pay for medicine – no problem, and if you need anything else – please... I’ll be indebted to him until my dying day, and I’m not the only one. It seemed that everyone who worked for his company was at his funeral. And they were all indebted to Sergey in some way or other. He helped them all, he did good deeds for them all. That’s why many of them came with their families and many of them cried. There just isn’t anyone else like Sergey, it’s impossible to compare anyone with him.’

He sharply felt the quick passing of time, the frailty of human memory. He wanted to save the names of people who had dedicated their lives to chess from oblivion, and he remembered many fantastic coaches, asking about Georgy Borisenko (1922), he wanted to find his address, knowing that even if the master now lived outside of Russia, he was completely alone and in great need.

He believed that elderly chess players were worthy of much attention while they were still alive. He himself never appeared at the parties and dinners for Moscow veterans, and they didn’t even know who had given money for these gatherings. When Igor Zaitsev became ill, he often visited him. Zaitsev recalls, ‘We were nodding acquaintances. We acknowledged each other if we met in the club, we exchanged a few words, perhaps, but nothing more. When I fell ill, Sergey started visiting me. I don’t know why, but I immediately trusted that man, he understood my problems and each of his visits gave me strength and vigour. When I needed money for an operation, he gave it to me. Without saying anything or asking for anything in return, he just came and gave it to me.’

When he heard about grandmaster Konstantin Aseev’s serious illness, he obtained medicine for him, called Petersburg, lifted his spirits. He helped Alexander Panchenko, who was indebted to him for many, many things, and there were few he didn’t help.

Once we talked about the portraits of people from the chess world that I had written. He liked the one about Max Euwe more than any of the others. Euwe? It was surprising to hear this particular name, especially comparing the modest Professor with the effervescent temperament and talent of the giants of the game whom I was lucky enough to meet on life’s path.

Now I think that Euwe’s emphatic modesty, his work ethic and his ability to hold on with dignity and fulfil his mission under any circumstances were the reason that the figure of the Dutch world champion seemed closest to him. And, more importantly, perhaps: he liked the role of a man who had left chess, was completely accomplished in society, then returned to it, this time in the capacity of its commander-in-chief. Perhaps he was even measuring himself up for this role?

Before he moved to the Moscow flat that would be his last home, he lived outside the city for three years. He really liked to walk, walking and walking for hours, he had developed his own routes there. He got himself some running shoes, and even rain didn’t bother him, he took an umbrella with him, and he could also manage without an umbrella. Always alone, contemplating. Did he know about the habits of the philosophers, who valued long solo walks so highly? Perhaps he did.

He also talked about the danger that was always close, and in his last years not only on the level of a street insult. Although Sergey was accepted among his friends and colleagues, for many others he became a foreigner after they cast a glance at his face. He knew this very well. He knew it and was afraid of it. His friends testify: this fear was always with him. Always. Did he sense a wave sent from the future? Who knows. But it was as if he felt something. Had a presentiment of it. He also said to his guys: ‘Don’t hang around just anywhere with nothing to do. Be on your guard...’

He avoided crowds of people. Once during the Tal memorial tournament he took me to the doors of the chess club on Gogolevsky Boulevard. I suggested, ‘Let’s go in for a minute, at least, Sergey, today’s round is interesting, Kramnik’s playing Shirov...’ ‘No, no, and don’t try and talk me into it, Genna, it’s packed with people, so and so will come up to me, then someone else. No, no, that’s not for me... If you have time before you leave, let me know, but don’t try and change my mind now, don’t change my mind...’ So he didn’t go into the club that day.

In his last years he sometimes gave his driver a break and used public transport. He liked riding on the metro, then also on trams, watching people, listening in on conversations.

On October 17, 2007 there was a big football match, Russia-England. He was afraid of big crowds of people, he was on the alert then, too, but nevertheless he went home on the metro. That day he decided to wait for the crowd to thin out. He usually left the office between four and four-thirty, but on this occasion he stayed at work until late for the first time in many years: he already had some kind of feeling of foreboding.

On October 20 he again went home on the metro. That day his soothsayer’s heart would be silenced, and it had just over an hour left to beat. He reached his station without incident. ‘Noviye Cheremushki’. He started strolling in the direction of his house. A group of teenagers, apparently skinheads. They started hassling and hectoring him.

After he died, some people claimed that Seryezha had made some kind of remark about them, providing a pretext to bring out their murder weapons. This wasn’t the case. In actual fact Nikolaev didn’t even answer them, he only walked faster, trying to get home as quickly as possible. This infuriated them even more. They attacked him. He fell.

Baseball bats and sharp instruments. Ten knife wounds. Death came almost instantly. Someone also set off a firecracker. It hit his coat. The coat caught on fire. It was in broad daylight; the street was full of people who saw everything. The first call to the police came half an hour after his death.

That day was declared by the teenagers to be a ‘raid’ day, they organized these ‘raids’ every weekend. People who looked obviously non-Slav were the ones who suffered. A young Armenian was killed. An Uzbek street sweeper received 12 knife wounds, survived, but was left disabled. The total number attacked on that day was 27.

They were caught accidentally – one was injured by his own murder weapon and went to the hospital. There they thought he was a victim at first. In his pocket they found a bloody knife and a mobile phone. They had photographed everything and posted the pictures on the internet afterwards. From their internet posts it was clear that they were proud of what they had done. They stressed that they didn’t have commercial motives, they didn’t touch any money, these weren’t robberies.

The police were called from the hospital. They went after the others. All of them except for one were minors. The incident got publicity. In newspaper articles and on websites they emphasized: an international chess master, a native of Yakutia, Sergey Nikolaev.

The trial took a year. In the dock even after their sentence was pronounced the defendants shouted ‘For Russia!’ and extended their arms in a Nazi salute: ‘We’ll build a new paradise, Sieg Heil! Sieg Heil!’ They celebrated and congratulated the older one when he was given less than the prosecutor had asked for, 10 years in a penal colony, and the others got three years and up.

When Sergey started talking about danger, the guys only laughed: ‘Papa, who’d bother with you...’ Now that he’s no longer here, his friends are experiencing pangs of conscience, because they were unable to prevent what happened. They reproach themselves: someone didn’t call, didn’t advise him not to travel by metro, someone else didn’t come to a meeting that was supposed to have been confirmed already, another lived a stone’s throw from him, and what would it have cost him to go out to the baker’s that day? An emotional, understandable reaction, but were they really to blame for Sergey’s death?

So who was, then? The boys? Teenagers between 14 and 16? La Fontaine wrote: this age doesn’t know compassion. But can the reason for the murder solely be explained by their being of an age when they didn’t understand the value of human life? Were they the only ones guilty of the crime?

Only 15-year-old Stasik Gribach, whom the investigation considered their leader? Reveling during the trial in his moment of glory and demonstratively standing in the glare of the photographers and TV reporters with his arm raised in a Nazi salute? His friends, who laughed when the sentence was pronounced and continued shouting, ‘Sieg Heil! Sieg Heil!’, when they were being escorted out of the courtroom? Their parents? The relatives of the accused, when the event degenerated into uncensored abuse with invitations to the journalists to ‘come outside and have a chat’? The ‘support group’ that gathered in the courtroom every day?

The Ministry of the Interior, which denied that there was an ethnic motive for the crime, calling the murder a ‘street conflict’? The deputy minister, who declared on the day after the boys’ arrest: ‘The reason for what happened was ordinary hooliganism. There’s no question of any kind of nationalist motive here’? Who is to blame for the fact that what happened, happened? Who is to blame for the fact that in Russia in 2008 alone, only according to official statistics, hundreds of people were killed or injured due to ethnic hatred? Who is to blame for the fact that in the country where Sergey Nikolaev was born and raised, he always felt like a second-class citizen, he was always afraid? Who?

He left us over a year ago. But, understandably, that isn’t all. His presence continues for those for whom his view of the world was decisive in their choice of life path. For those who, without realizing it themselves, adopted one of the features of his personality, a habit or an expression of his. And for those who smile just recalling him, wondering what Sergey would have said in this situation, what new idea would he have dreamed up? His spirit lingers over them.

■ ■ ■

October 2022 marked fifteen years since the murder of Sergey Nikolaevich Nikolaev. The one whom the investigation considered the main culprit of the crime, the then fifteen-year-old Stanislav Gribach, was released a few years after the trial. His other accomplices, who were minors at the time of the crime, have also been free for a long time.

One of them recalls: ‘Just as companies go to a bar or a nightclub, so we were doing so. Only we just went to kill people. In the evening we killed someone, and in the morning we watched the news reports – who did we kill there? Then we also boasted to our friends: “It was us!”’

Another of the same group: ‘In different groups, we carried out attacks on non-Slavs for seven or eight months, and it all ended with the murder of a chess player. I remember that case: he was a non-Slav, whom we beat up on the train, and an old couple was sitting on the bench and shouting: “Well done!” The same thing happened at the railway station, when we beat two non-Slavs, and a couple of men said: “Well done, guys, you’re knocking some sense into the blockheads!”’

The last member of that gang, the only adult, who received ten years in prison, has also been released. He is still proud of his past and has not repented of anything: ‘How did we kill the Yakut chess player? Yes, we met at the subway, looked into the first courtyard, some guy photographed us. We covered our faces with masks and showed the knives in our hands. The photographer turned out to be up for a fight. We went and noticed four migrant workers. While we were discussing the attack, we noticed some kind of “slit-eye” walking towards us. It was the chess player. One of us immediately ran to him and stabbed him in the stomach. Another began to stick a knife into his back and side, a third plunged a knife into his neck; another threw a flare in his face. I, waving the bat, began to beat him, and shouted “Die!” The Yakut, still able to speak, shouted “Eh, I have family!” But that didn’t help him. Then we went to some park. A couple of “blacks” were walking past us. We jumped on the Caucasian, and pummelled him with feet and fists. Since then, I have regularly participated in actions. They happened everywhere: in the courtyards of houses, on the street, in the subway, in electric trains. With different guys, I crushed the enemies of our race.’

Similar attacks took place not only in Moscow. At the same time Nikolaev was killed, similar ‘raids’ were carried out in other cities. In St. Petersburg, young Uzbeks and Azerbaijanis were mortally wounded, and to the cries of ‘get out of Russia!’, ‘Beat the blacks!’ a Tajik girl was also killed.

These attacks, which were reported with frightening frequency in the newspapers, were far from the last reason Anish Giri’s family left Russia.

Although today in the Russian media you can read about racial attacks from time to time, this problem does not seem as relevant as at that time. Surveillance cameras now hang everywhere and the chance that you will be identified, caught and sentenced is much higher than before.

But the main explanation, it seems to me, is not this. It’s just that the place of ‘wogs’, ‘yids’ and ‘chinks’ has been taken by Yanks, Brits and ‘Ukrops’, as Ukrainians have long been insultingly referred to in Russia, and with whom there is already a real bloody war. It is at them that today the hate sessions broadcast daily by the federal channels of Russian television are directed.

But the problem, although swept under the carpet, has not gone away. Reports of ethnic squabbles and murders in the Russian army during the war with Ukraine regularly appear in the media. Whatever the future of Russia after Putin, it is clear that this problem has yet to be solved by a multi-ethnic and multi-religious country.