Extraordinary inventiveness

It started with his childhood coach, who mentioned the games of Sergio Mariotti, or ‘The Italian Fury’. This led to reading two books about Albin Planinc, a genius of the same category who has almost been forgotten.

These book reviews by Matthew Sadler were published in New In Chess magazine 2025#7

This month’s column is a little different because due to a logistical mix-up, I ended up a little short of books! So I’m focusing this time on the books I’ve bought recently myself, my reasons for doing so and what I’ve discovered!

The first set of books I’d like to discuss are Apologia of the Unexpected – Selected Games of Albin Planinc by Pablo Iglesias (Amazon, self-published) and Forgotten Genius – The Life and Games of Grandmaster Albin Planinc by Georg Mohr and Adrian Mikhalchishin (Thinkers Publishing). As you may gather, I’ve developed an interest in the games of this Slovenian Grandmaster (1944-2008) who for a brief period (1968-1975) dazzled the chess world with games and concepts of extraordinary inventiveness and beauty. So where did my interest originate?

The first set of books I’d like to discuss are Apologia of the Unexpected – Selected Games of Albin Planinc by Pablo Iglesias (Amazon, self-published) and Forgotten Genius – The Life and Games of Grandmaster Albin Planinc by Georg Mohr and Adrian Mikhalchishin (Thinkers Publishing). As you may gather, I’ve developed an interest in the games of this Slovenian Grandmaster (1944-2008) who for a brief period (1968-1975) dazzled the chess world with games and concepts of extraordinary inventiveness and beauty. So where did my interest originate?

Well, as is the case for many things at the moment, it all started with the Italian Grandmaster Sergio Mariotti, another such shining star of creativity during the late sixties and seventies. My childhood coach Steve Giddin had mentioned his name to me during a coaching session, but it took more than forty years before my brain engaged and started to look for information about him! I was surprised that no biography had been written of him, but Steve dug up a 1975 British Chess Magazine article by Jimmy Adams. As anyone who has had the good fortune to read other works by him (not least the recent four-volume series on Paul Keres) you will guess that it is very long and very good! Jimmy was also the man who came up with the nickname for Mariotti that has been used since: ‘The Italian Fury’! Many thanks too to Gerard Welling, who supplied me with a vast amount of information about Mariotti’s openings, many of which used ideas from the German amateur Gunderam, such as this immortal anti-King’s Indian played against Gligoric in 1969:

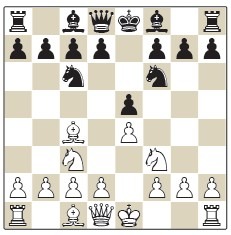

1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 ♗g7 4.e4 d6 5.f4 c5 6.d5 0-0 7.♗e2 e6 8.dxe6 fxe6 9.g4 The link with Planinc came from a game they disputed at the Vidmar Memorial in 1975 (with Planinc White and Mariotti Black) and, as you would expect, the game was not short of fireworks:

The link with Planinc came from a game they disputed at the Vidmar Memorial in 1975 (with Planinc White and Mariotti Black) and, as you would expect, the game was not short of fireworks:

1.e4 c5 2.♘f3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.♘xd4 a6 5.♗e2 ♘f6 6.♘c3 ♕c7 7.0-0 d6 8.f4 h5 9.h3 ♘bd7 10.a4 b6 11.f5 e5 12.♘e6 Twelve moves in and we’ve already had ...h5 from Mariotti and a knight sacrifice from Planinc! (For those interested, this and many other Mariotti games are analysed on my Silicon Road YouTube channel.) Planinc lost that game from a winning position (something that tragically afflicted him ever more as his nerves gained the upper hand) but my interest had been piqued.

Twelve moves in and we’ve already had ...h5 from Mariotti and a knight sacrifice from Planinc! (For those interested, this and many other Mariotti games are analysed on my Silicon Road YouTube channel.) Planinc lost that game from a winning position (something that tragically afflicted him ever more as his nerves gained the upper hand) but my interest had been piqued.

As I always do whenever I want to learn more about any chess topic, I searched around for some books to start with and I found these two. Apologia of the Unexpected – Selected Games of Albin Planinc by Pablo Iglesias (Amazon, self-published, 2020) is just a couple of hundred pages, with 31 lightly-annotated games in very large print format, and in principle it’s not a super book.

In particular, the annotations are not particularly trustworthy, more reminiscent of the 1980s than the computer age. However, it is suffused with a tremendous enthusiasm for Planinc’s games – very much in the style of Irving Chernev in his The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played, of which I have very fond memories – and with a diagram on pretty much every page, it’s easy to marvel at spectacular moves!

Albin Planinc

Srdjan Marangunic

Novi Travnik 1969 17.♕xg6!!

17.♕xg6!!

It’s one of those books that I couldn’t really recommend to anyone else, but that I certainly did not regret buying as a first step into a new world!

Forgotten Genius – The Life and Games of Grandmaster Albin Planinc is a much weightier work (437 pages), comprised of 85 annotated games and a wealth of biographical detail accompanied by reminiscences and anecdotes from his erstwhile colleagues and I enjoyed it greatly. It’s again one of those stories that leaves you staggered at how someone so lacking in formal chess training and any kind of support could become so strong that he could challenge and even outclass the very best in the world, as he did for example in Amsterdam 1973, sharing first place with Petrosian with 10/15 (7 wins, 2 losses) ahead of Spassky, Kavalek, Szabo, Andersson, Ribli, Donner, Smejkal, Timman and Quinteros.

His career was extremely short, starting in 1961 and then interrupted in 1965 after a one-and-a-half year ban for inappropriate behaviour (the circumstances are detailed in the book). He restarted his chess career in real earnest in 1968, in the beginning as an amateur, having started work in a bicycle factory during his suspension from chess.

It’s quite strange to notice certain parallels and common ‘victims’ between Mariotti and Planinc. Certainly, the great Svetozar Gligoric played a significant role in promoting both of these players. Gligoric first lost that crazy King’s Indian to Mariotti in 1969 and then a very cool Evans Gambit in Venice in 1971, The tactics started here...

Sergio Mariotti

Svetozar Gligoric

Venice 1971 33.♗xf6! ♕e4

33.♗xf6! ♕e4

...and ended with

34.♘g6!!

However, already in 1968, Planinc had caused a sensation by defeating Gligoric with his beloved King’s Gambit!

Albin Planinc

Svetozar Gligoric

Yugoslavia 1968

King’s Gambit

1.e4 e5 2.f4 d5 3.exd5 exf4 4.♕f3 His play in the next years was marked by a huge will to win, innovative opening ideas and a seemingly inexhaustible creativity at the board. As always with such players, there were always weak moments – often, inexplicably, in the middle of tournaments in which he was playing brilliantly – but his play also deepened as his experience increased.

His play in the next years was marked by a huge will to win, innovative opening ideas and a seemingly inexhaustible creativity at the board. As always with such players, there were always weak moments – often, inexplicably, in the middle of tournaments in which he was playing brilliantly – but his play also deepened as his experience increased.

Another player that featured in both Mariotti’s and Planinc’s ‘hitlist’ was the young, somewhat less-solid-than-we-know-him but already very strong Ulf Andersson. And by a strange twist of fate, they did it in the same tournament!

Mariotti did this to Ulf (yes that is Ulf playing the Modern in his youth!):

Sergio Mariotti

Ulf Andersson

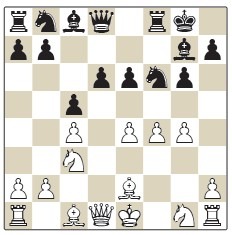

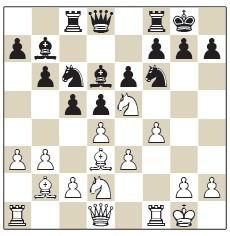

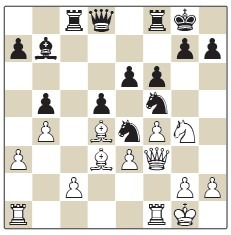

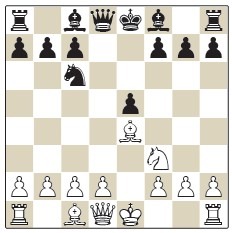

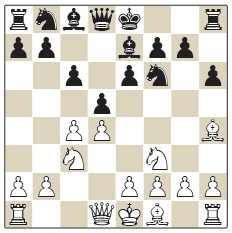

Sombor 1970 (5) While in this position Planinc unleashed one of the most gasp-inducing moves I’ve seen this year!

While in this position Planinc unleashed one of the most gasp-inducing moves I’ve seen this year!

Albin Planinc

Ulf Andersson

Sombor 1970 (15) It was 19.♖e5!!, which still makes me go ‘Oooh!’ even after seeing it many times!

It was 19.♖e5!!, which still makes me go ‘Oooh!’ even after seeing it many times!

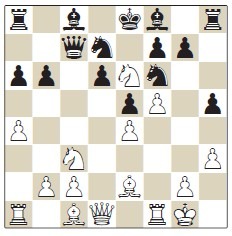

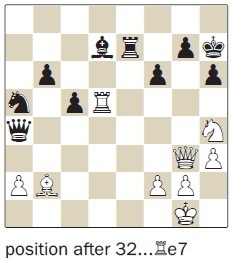

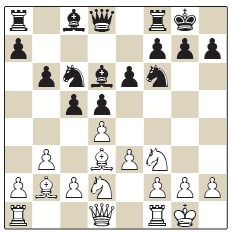

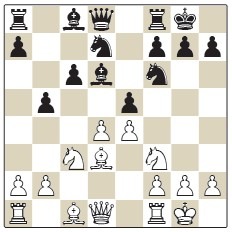

At Hastings 1974/75, Planinc finished in sixth place, after a last-round loss to Hort, but he still produced glorious games, such as a fantastic Sicilian demolition of then-Soviet Champion Alexander Beliavsky and a finish against Rafael Vaganian that sealed Planinc’s place in the history books, or at the very least the puzzle books!

Rafael Vaganian

Albin Planinc

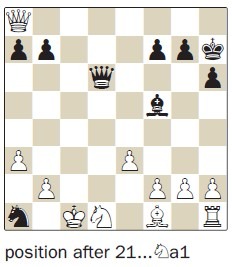

Hastings 1975 Some brilliant play from Planinc had set up the threat of ...♘b3 +mate after his last move 21...♘a1. It was only fitting that Vaganian played

Some brilliant play from Planinc had set up the threat of ...♘b3 +mate after his last move 21...♘a1. It was only fitting that Vaganian played

22.♕xb7? allowing the glorious 22...♕c7+! 0-1.

And yet after that somehow, Planinc’s chess seemed to collapse. The book gives many possible reasons for this, but the outward effect was that he was no longer able to sustain the enormous effort required or survive the tension he created himself with his style. 1979 featured his last international tournament (the Rubinstein Memorial) and his chess activity tailed off quickly. No more was seen of him in Slovenian chess circles after 1985 (although there is just one game from 1991 at an open in Austria in ChessBase). He died in December 2008, a few months after his mother, for whom he had cared all his life.

All-in-all, this is a really good book, and a really good guide to the life and games of an astonishing player. I’ll give it 4 stars!

I noticed by the way – my finger is on the ordering button already – that one of the authors has produced a similar work on Planinc’s rival and friend Dragoljub Velimirovic, another staggeringly inventive player! There remains so much to discover in chess! Something else that really grabbed my attention recently was the 2025 British Championships in Liverpool, which turned out to be an extremely exciting tournament. There were many interesting narratives throughout the tournament, one of which was veteran (seems strange to describe him like that, but he does play for the English senior team!) Stuart Conquest’s brilliant final run, defeating Shreyas Royal and Nikita Vitiugov to secure a spot for himself in a play-off for first place.

Something else that really grabbed my attention recently was the 2025 British Championships in Liverpool, which turned out to be an extremely exciting tournament. There were many interesting narratives throughout the tournament, one of which was veteran (seems strange to describe him like that, but he does play for the English senior team!) Stuart Conquest’s brilliant final run, defeating Shreyas Royal and Nikita Vitiugov to secure a spot for himself in a play-off for first place.

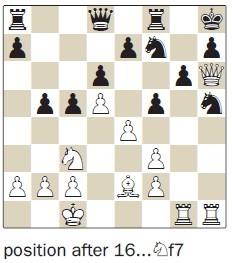

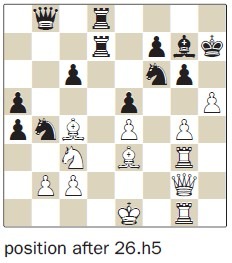

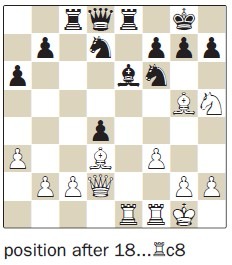

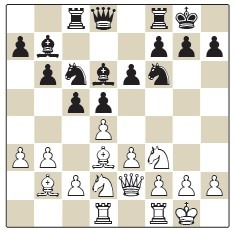

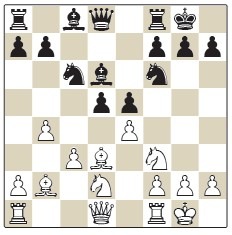

The game against Shreyas particularly interested me because it featured a lightning attack from a typical setup (a Colle-Zukertort by transposition).

This was the game:

Stuart Conquest

Shreyas Royal

Liverpool 2025

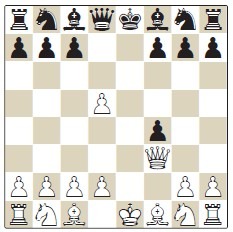

1.b3 ♘f6 2.♗b2 c5 3.e3 d5 4.♘f3 e6 5.d4 ♘c6 6.♘bd2 ♗d6 7.♗d3 0-0 8.0-0 b6 9.a3 ♗b7 10.♘e5 ♖c8 11.f4 11...♘e7 12.♕f3 b5 13.dxc5 ♗xc5 14.b4 ♗b6 15.♘b3 ♘e4 16.♘d4 ♘f5 17.♖ad1 ♕e7 18.♔h1 a6 19.♕h3 ♘fd6 20.f5 f6

11...♘e7 12.♕f3 b5 13.dxc5 ♗xc5 14.b4 ♗b6 15.♘b3 ♘e4 16.♘d4 ♘f5 17.♖ad1 ♕e7 18.♔h1 a6 19.♕h3 ♘fd6 20.f5 f6 21.♘g6 hxg6 22.fxg6 ♘g5 23.♕h5 ♖fd8 24.♘f3 ♘gf7 25.gxf7+ ♘xf7 26.♕h7+ ♔f8 27.♘h4 ♔e8 28.♘g6 1-0.

21.♘g6 hxg6 22.fxg6 ♘g5 23.♕h5 ♖fd8 24.♘f3 ♘gf7 25.gxf7+ ♘xf7 26.♕h7+ ♔f8 27.♘h4 ♔e8 28.♘g6 1-0.

Real power play from Stuart and his moves all seemed natural and flowing right from the opening. A quick glance at the game and you feel that this line is almost a forced win for White! However, some deeper analysis (I’m dedicating a seven-part series to this on my blog) showed that things were far from clear. To mention one line, after 16.♘d4, even the unexpected

16...♗xd4 17.♗xd4 f6 18.♘g4 ♘f5 ...gives Black a wonderful position.

...gives Black a wonderful position.

I was intrigued what the theoretical status of the line was so I once again looked around for some books. I guess I’m showing my age here because the most obvious place to start would be a Chessable video course like The Killer Colle-Zukertort System by the always excellent Simon Williams and Richard Palliser. However, although video courses are a pleasant way to learn something from scratch, I find them quite frustrating when I’m trying to zoom into something specific. So I ended up with a hardback edition of The Modernized Colle-Zukertort Attack by Milos Pavlovic (Thinkers Publishing) I’m reviewing a lot of opening books by Pavlovic at the moment. He’s not one of my absolute favourite openings authors, but he has an enviable knack of finding worthwhile material in boring lines! That sounds a little rude, but it’s meant to be a compliment as this is probably the major skill in opening preparation in modern times. I noticed that he had played quite a few games with 1.d4 ♘f6 2.♘f3 d5 3.e3 so I was wondering what he had in mind.

I’ve often noticed that your opening preparation undergoes several transformations. You start with low knowledge but high positivity and good results; strangely as you learn more, your results decrease as you realise that what attracted you to the line isn’t as good as you thought! The example I always give is this trick I learnt as a beginner:

1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♘c3 ♘f6 4.♗c4. A very common opening in junior chess in my day, and now 4...♘xe4 breaks up White’s normal pattern of play, with the basic idea 5.♘xe4 d5, regaining the piece.

A very common opening in junior chess in my day, and now 4...♘xe4 breaks up White’s normal pattern of play, with the basic idea 5.♘xe4 d5, regaining the piece.

I won so many games, simply filled with energy from the joy of implementing this idea! After a little while, I began to understand that my advantage after 6.♗d3 dxe4 7.♗xe4 was actually not that great... or non-existent to be precise! And with that knowledge, I lost my buzz and my results went down!

was actually not that great... or non-existent to be precise! And with that knowledge, I lost my buzz and my results went down!

That was my feeling when reading the book by Pavlovic. I love Stuart’s attacking play and I would like to play the line in that way. However, Pavlovic – marked by experience I imagine – was recommending lots of specific ways to sidestep getting into this sort of structure! For example, after 1.d4 ♘f6 2.♘f3 d5 3.e3 e6 4.♗d3 c5 5.0-0 ♗d6 6.b3 0-0 7.♗b2 ♘c6 8.♘bd2 b6, instead of 9.a3 ♗b7 10.♘e5 ♖c8 11.f4, which would lead into Conquest-Royal, Pavlovic suggests 9.dxc5 ♗xc5 10.a3, looking for b4 and c4.

instead of 9.a3 ♗b7 10.♘e5 ♖c8 11.f4, which would lead into Conquest-Royal, Pavlovic suggests 9.dxc5 ♗xc5 10.a3, looking for b4 and c4.

He considers 8...♘b4 the strongest move order when after 9.♗e2 b6 10.a3 ♘c6 11.♗d3 ♗b7 we are heading back to Conquest-Royal but now Pavlovic recommends 12.♕e2 ♖c8 13.♖ad1 looking for dxc5 followed by either c4 or e4. It’s pretty interesting but it doesn’t have the joy of sticking a knight on e5, playing f4 and throwing everything at the Black king!

looking for dxc5 followed by either c4 or e4. It’s pretty interesting but it doesn’t have the joy of sticking a knight on e5, playing f4 and throwing everything at the Black king!

It makes me believe that there truly is an important place for ignorance in opening preparation! I found this book useful, although I got a little confused at times trying to sort out the move orders. This was particularly so when the move order given in a specific line differed from the move order in the title of the section. But if you want some fresh, more positional ideas in this line on top of the standard attacking ones, then Pavlovic has you covered! 3 stars! We’ll finish with The Semi-Slav by Nicolas Yap (Popular Chess).

We’ll finish with The Semi-Slav by Nicolas Yap (Popular Chess).

I reviewed Yap’s previous book on the Queen’s Gambit Accepted which I found quite striking as I didn’t recognise most of the lines he was recommending – showing how much the opening has changed since I was an expert in it! I was half-expecting to have the same feeling with the Semi-Slav complex but this time the sentiment is less extreme. It did start with raised eyebrows due to the recommendation (a secondary one) of meeting

1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.♘f3 ♘f6 4.♘c3 e6 5.♗g5 with 5...h6 6.♗h4 ♗e7 I’d already seen quite a bit of this from Stockfish 8 in matches with AlphaZero via the move order 5...♗e7 6.e3 h6, so I wasn’t too surprised by the line, but I was a bit shocked to hear this described as a ‘weird QGD where Black has an early ...c7-c6 in’. As anyone from my generation – brought up on games from the early 1900s – will tell you, this is an Orthodox QGD with a strangely early ...h6 thrown in! Generation gap, I think!

I’d already seen quite a bit of this from Stockfish 8 in matches with AlphaZero via the move order 5...♗e7 6.e3 h6, so I wasn’t too surprised by the line, but I was a bit shocked to hear this described as a ‘weird QGD where Black has an early ...c7-c6 in’. As anyone from my generation – brought up on games from the early 1900s – will tell you, this is an Orthodox QGD with a strangely early ...h6 thrown in! Generation gap, I think!

However, after that the recommendations are much more mainstream. Simply speaking, the main lines in the anti-Moscow Gambit (1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.♘f3 ♘f6 4.♘c3 e6 5.♗g5 h6 6.♗h4 dxc4) and the Meran (1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.♘f3 ♘f6 4.♘c3 e6 5.e3 and then either 6.♕c2 or 6.♗d3) have been so well worked out for Black that there isn’t much point in looking at anything else. Fresh from Pavlovic’s book on the Colle however, it was a shock to realise that the Semi-Slav Meran is just a Colle Reversed! For example, Yap’s

1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.♘f3 ♘f6 4.♘c3 e6 5.e3 ♘bd7 6.♗d3 dxc4 7.♗xc4 b5 8.♗d3 ♗d6 (Zvjaginsev’s move, which Yap recommends) 9.0-0 0-0 10.e4 e5 looks a lot like Pavlovic’s 1.d4 d5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.e3 e6 4.♗d3 c5 5.c3 ♘c6 6.♘bd2 ♗d6 7.0-0 0-0 8.dxc5 ♗xc5 9.b4 ♗d6 10.♗b2 e5 11.e4.

looks a lot like Pavlovic’s 1.d4 d5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.e3 e6 4.♗d3 c5 5.c3 ♘c6 6.♘bd2 ♗d6 7.0-0 0-0 8.dxc5 ♗xc5 9.b4 ♗d6 10.♗b2 e5 11.e4. The positions are so similar that I have ended up worse with both White and Black when practising against engines! I guess I should have realised that similarity a bit earlier in my 40+ years chess career...

The positions are so similar that I have ended up worse with both White and Black when practising against engines! I guess I should have realised that similarity a bit earlier in my 40+ years chess career...

A useful book in summary for all those Semi-Slav fans out there: 3 stars! ■