Forgotten Genius

Velimirovic is a player whose name will always remain immortal in the collective chess memory. But he had a career that was characterized by strange hiccups and odd twists of fate, robbing him of many opportunities.

These book reviews by Matthew Sadler were published in New In Chess magazine 2025#8

I left you on a cliffhanger in the last issue with my finger poised over the ‘order’ button for both volumes of Forgotten Genius – The Life and Games of Grandmaster Dragoljub Velimirovic by Georg Mohr and Ana Velimirovic-Zorica. Well, the story continues happily, as I did order them and loved them both! The book is co-written by the Slovenian player and journalist Georg Mohr and Velimirovic’s daughter Ana. Mohr also co-wrote a volume on Velimirovic’s contemporary Albin Planinc, reviewed in a previous issue. Ana’s involvement adds a special touch to these two volumes. She not only had a large collection of photos and cartoons of her father (many of which appear in both volumes) but also Velimirovic’s extensive annotations to his own games, which also, in passing, contained anecdotes and stories from his life. Mohr has spoken with Velimirovic’s contemporaries, who shared their memories of him.

The book is co-written by the Slovenian player and journalist Georg Mohr and Velimirovic’s daughter Ana. Mohr also co-wrote a volume on Velimirovic’s contemporary Albin Planinc, reviewed in a previous issue. Ana’s involvement adds a special touch to these two volumes. She not only had a large collection of photos and cartoons of her father (many of which appear in both volumes) but also Velimirovic’s extensive annotations to his own games, which also, in passing, contained anecdotes and stories from his life. Mohr has spoken with Velimirovic’s contemporaries, who shared their memories of him.

And of course there are the games! Just like Planinc, Velimirovic was a Modern Benoni addict but handled it completely differently (...♘bd7 instead of Planinc’s inveterate ...♘a6) and there are many Open Sicilians with the inevitable Velimirovic knight sacs on f5 and d5! I dare anyone to play through the games in this collection without regular ‘Oohs’ and ‘Aahs’!

For example, there is no shortage of Velimirovic Attacks!

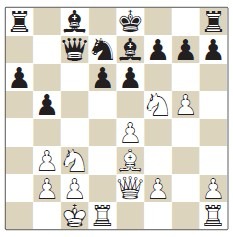

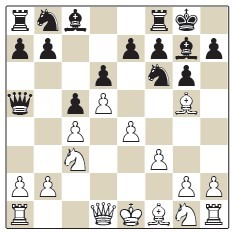

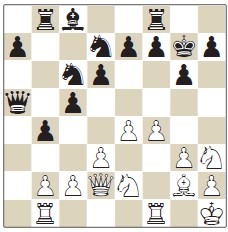

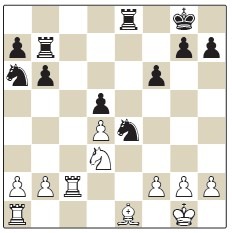

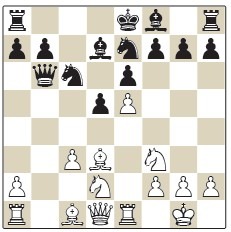

1.e4 c5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.d4 cxd4 4.♘xd4 e6 5.♘c3 d6 6.♗e3 ♘f6 7.♗c4 ♗e7 8.♕e2 With the typical follow-up:

With the typical follow-up:

8...a6 9.0-0-0 ♕c7 10.♗b3 ♘a5 11.g4 b5 12.g5 ♘xb3+ 13.axb3 ♘d7 14.♘f5 I knew absolutely nothing about Velimirovic’s life before reading this book, and it was somewhat of a shock to read that a player whose name will always remain immortal in the collective chess memory had such an unsteady position with his national chess federation. His career was characterized by strange hiccups and odd twists of fate that slowed his progress and likely robbed him of the opportunity to reach still greater heights. For example, at the very start of his career in 1962, he finished 3rd/4th in the Yugoslav Championships – a sensational result for a Category I player. He might have finished higher but for his only loss as White to Parma in the penultimate round, sacrificing a queen for insufficient material in a rather cavalier style inappropriate for such a critical game. No disaster: the top five places qualified for the Zonal anyway! Only... they didn’t. Unbeknown to him (and perhaps also to most players in the tournament) the Yugoslav federation had decided that his placing would only qualify him for a qualifying tournament for the Zonal. Velimirovic believed that an injustice had been done to him and had an absolute nightmare, finishing far behind the other participants with 3/14.

I knew absolutely nothing about Velimirovic’s life before reading this book, and it was somewhat of a shock to read that a player whose name will always remain immortal in the collective chess memory had such an unsteady position with his national chess federation. His career was characterized by strange hiccups and odd twists of fate that slowed his progress and likely robbed him of the opportunity to reach still greater heights. For example, at the very start of his career in 1962, he finished 3rd/4th in the Yugoslav Championships – a sensational result for a Category I player. He might have finished higher but for his only loss as White to Parma in the penultimate round, sacrificing a queen for insufficient material in a rather cavalier style inappropriate for such a critical game. No disaster: the top five places qualified for the Zonal anyway! Only... they didn’t. Unbeknown to him (and perhaps also to most players in the tournament) the Yugoslav federation had decided that his placing would only qualify him for a qualifying tournament for the Zonal. Velimirovic believed that an injustice had been done to him and had an absolute nightmare, finishing far behind the other participants with 3/14.

Also in 1966, despite finishing in shared 4th-5th place in the Yugoslav Championships, he was again denied one of the six qualification places for the Zonal when the national federation suddenly decided to organise a playoff for the qualifying spots between the players who had finished 4th to 10th! This time he managed to qualify but only thanks to a bizarre final-round win! His opponent, Mario Bertok, thought for a long time on his 40th move and lost on time in a drawn position.

So Velimirovic qualified for the Zonal, but that year – perhaps as a result of his complaints about the qualifying process – he was kicked out of the national team for the Havana Olympiad. The Zonal at The Hague finished in desperate disappointment as he failed to advance to the Interzonals at the last hurdle, unable to win a very promising position against the Spanish player Diaz del Corral.

Sad, but there would always be more chances in the next cycles? True and indeed there were. But in Velimirovic’s career, you can see how much importance he placed on the qualification cycle for the World Championship and how much effort he put into peaking at the right moment for this tournament. And how great the disappointment was when it went wrong: both after 1962 and 1966, the next couple of years were somewhat empty years for Velimirovic, which must have cost him some opportunities to shine when he was still young and full of energy!

Of course, Velimirovic’s playing style and general chess approach also played a role in his peaks and troughs. For example, in the 1965 National Championship, he finished with 10 wins, 7 losses, and a single draw in the last round (after a sacrificial Sicilian Poisoned Pawn!). With such a style and fighting spirit, it’s not surprising to encounter a mix of triumphs and disasters! Perhaps the most surprising thing about Velimirovic’s career was the esteem he enjoyed as a trainer and analyst, first as an assistant to Gligoric, then as a second to Viktor Korchnoi in 1982 and 1983, and finally as a coach to many juniors from the former Yugoslavia, such as Ivan Sokolov and Alexander Indjic. I hadn’t expected a great player and fighter like him to be able to share easily the knowledge he had acquired, but judging from the many warm tributes from his students, he most certainly was!

Perhaps the most surprising thing about Velimirovic’s career was the esteem he enjoyed as a trainer and analyst, first as an assistant to Gligoric, then as a second to Viktor Korchnoi in 1982 and 1983, and finally as a coach to many juniors from the former Yugoslavia, such as Ivan Sokolov and Alexander Indjic. I hadn’t expected a great player and fighter like him to be able to share easily the knowledge he had acquired, but judging from the many warm tributes from his students, he most certainly was!

How do you choose one single game for this review to illustrate such a wonderful player? In the end, I discovered a game in this book that perfectly demonstrates Velimirovic’s remarkable feel for Benoni positions, overwhelming the extremely strong Mikhail Gurevich, who had sensationally won the Soviet Championship in the year this game was played.

Mikhail Gurevich

Dragoljub Velimirovic

Vrsac 1985

Modern Benoni

1.d4 c5 2.d5 d6 3.c4 ♘f6 4.♘c3 g6 5.e4 ♗g7 6.f3 0-0 7.♗g5 ♕a5 A Velimirovic speciality with a pretty good result against strong players: 3½/4!

A Velimirovic speciality with a pretty good result against strong players: 3½/4!

8.♕c2!?

The queen normally goes to d2, but Gurevich reserves this square for the dark-squared bishop to oppose the queen on the a5-e1 diagonal if necessary.

8...a6 9.♗d2

To meet 9...b5 with 10.♘xb5.

9...♕d8 10.a4 e6 11.♗g5 exd5 12.cxd5 ♖e8

The net result of Black’s ...♕a5-d8 manoeuvre is that White has played a normal system with the white queen on the unusual square c2 rather than the normal d2.

13.♘ge2 h6 14.♗e3 ♘bd7 15.♘g3 h5

A typical disruptive idea for Black in this line when White plays 15.♘g3. Gurevich, however, tries to use the unusual position of the queen on c2 to turn the chasing of this knight into a strong redeployment: the knight will be transferred to c4 via f1-d2.

16.♗e2 h4 17.♘f1 ♘e5 18.♗g5

A very ambitious move from Gurevich. Most players would have developed with 18.♘d2 followed by 0-0 and been happy to get the king out of the centre!

However, the engines prefer 18...♘h5 19.0-0 g5 for Black. This explains why they prefer Gurevich’s move, which obstructs Black’s attempts to take over the kingside dark squares.

18...h3 19.g3 ♕a5

Velimirovic can’t resist putting the queen back on a5!

20.♗d2

And Gurevich responds in kind!

20...c4 21.♖a3 ♗d7

Other options, such as 21...♘d3+ 22.♗xd3 cxd3 23.♕xd3 ♘d7 aimed at exploiting White’s weak light squares all over the board (c4, d3, f3) was another approach, but Velimirovic’s calm development remained strong. Gurevich tries to draw some advantage from the opposition of queen and bishop along the a5-e1 diagonal, but only manages to increase Black’s dynamic advantage. And those are situations in which Velimirovic truly excelled.

22.♘b5 ♕d8 23.♘xd6 ♗xa4 24.♖xa4 ♕xd6 25.♗b4 ♕d7 26.♖a3 26...a5

26...a5

26...♘xd5 immediately was also very strong, but Velimirovic wants the a-file open too!

27.♖xa5 ♖xa5 28.♗xa5 ♘xd5 29.♗d2

29.exd5 ♘xf3+ 30.♔d1 ♕xd5+ is catastrophic for White of course.

29...♕b5

A very nasty and far from obvious move, reinforcing the entry of the black knight on d3.

30.♘e3 ♘d3+ 31.♗xd3 ♘xe3 32.♗xe3 cxd3 33.♕c1 ♗xb2

Pretty much the nightmare of any player of the Sämisch structure! The solid Sämisch centre counts for nothing and your king is still caught in the centre after more than 30 moves!

34.♕c7 ♕b4+ 35.♔f2

First move of the king!

35...♗d4 36.♕c1 ♖a8 37.♖e1

First move of the rook!

37...♖a2+ 38.♔f1 ♖c2 0-1

The type of game that makes you want to take up the Modern Benoni as Black!

The book is a wonderful tribute to a fantastic player. I also loved it for the insights into the players and events of Yugoslav chess (as it then was) at a time when Yugoslavia was the second strongest country in the world.

Definitely recommended for all those adult ‘chess enjoyers’ out there! 5 stars! Many years ago, waiting idly with some other players for the tournament prize-giving to start, I got into a little game of thinking up the most unlikely chess book titles. I’m pretty sure that ‘Ulf Andersson’s Attacking Games’ came up as one of those! No disrespect meant, of course, to the great Swedish player, but with him, it was the (long) endgames we watched out for, not the king hunts! However, that unlikely book is now here: Ulf the Attacker – 56 Thrilling Games from Sweden’s Chess Legend by Thomas Engqvist annotates 56 games and game snippets, highlighting a less appreciated side of Andersson’s play.

Many years ago, waiting idly with some other players for the tournament prize-giving to start, I got into a little game of thinking up the most unlikely chess book titles. I’m pretty sure that ‘Ulf Andersson’s Attacking Games’ came up as one of those! No disrespect meant, of course, to the great Swedish player, but with him, it was the (long) endgames we watched out for, not the king hunts! However, that unlikely book is now here: Ulf the Attacker – 56 Thrilling Games from Sweden’s Chess Legend by Thomas Engqvist annotates 56 games and game snippets, highlighting a less appreciated side of Andersson’s play.

The unwary reader may be shocked to see Ulf playing the White side of the 6.♗g5 Najdorf, or the Modern and Pirc as Black, but indeed until about 1973 he kept on playing the openings

with which he had grown into chess. Somehow, after that date, however, he seemed to switch style and opening repertoire quite significantly. The examples of attacking play after that date are a little less convincing until his correspondence games enter the scene which are indeed again full of verve and aggressive play.

It’s intriguing to think about what might have happened with Andersson around that time: did a change in openings allow him to discover his true style and make him realise his full potential, or did he simply become more conservative as a practical strategy? I always think of the change I made when I was around twelve, when I moved from rather stodgy, nontheoretical openings to sharp lines like the King’s Indian Four Pawns and Sämisch system against the Nimzo-Indian. I made a huge jump in strength and got close to International Master level and I’ve always believed that this switch in openings was needed to get me into the types of positions I played best. If I hadn’t made that switch, the chess skills I had might have remained buried for a lot longer. I wonder if this was something similar for Andersson?

However, let me show you Ulf on the attack in this 1969 game!

Ulf Andersson

Zbigniew Doda

Lodz 1969

Sicilian Defence, Closed Variation

1.e4 c5 2.♘c3 ♘c6 3.g3 g6 4.♗g2 ♗g7 5.d3 d6 6.♘h3 Ulf played the Closed Sicilian a few times but varied the position of his knight each time: once on h3, once on e2 and once on f3 (after f4).

Ulf played the Closed Sicilian a few times but varied the position of his knight each time: once on h3, once on e2 and once on f3 (after f4).

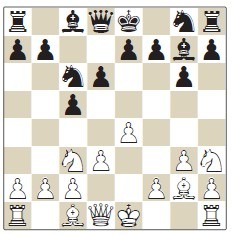

6...♘f6 7.♗e3 ♖b8 8.0-0 0-0 9.♔h1 b5 10.f3

A slightly odd move, most likely to prepare f4 after a preliminary ♘f2 so as not to allow ...♘g4.

10...b4 11.♘e2 ♘d7 12.♖b1 ♕a5 13.♕d2

Ulf sacrifices a pawn for an attack!

13...♕xa2 14.♗h6

Exchanging the opponent’s fianchettoed bishop was a favourite mechanism of the young Ulf.

14...♕a5 15.♗xg7 ♔xg7 16.f4 White’s compensation for the pawn is pretty speculative, but as we know from modern engines, the rook’s pawn is the best pawn to lose/sacrifice: it causes the least structural damage to the sacrificer and activates a rook!

White’s compensation for the pawn is pretty speculative, but as we know from modern engines, the rook’s pawn is the best pawn to lose/sacrifice: it causes the least structural damage to the sacrificer and activates a rook!

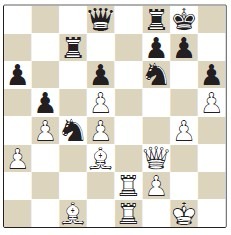

16...♘d4 17.♘xd4 cxd4 18.f5 ♘f6 19.♖f4

A rook lift from Ulf! I don’t think that anyone would ever guess who was handling the white pieces!

19...♖h8 20.♖bf1 h6 21.♖h4 ♗d7 22.g4 ♕c5

It’s not very easy to see what White is actually threatening in this position, despite the number of pieces he has moved to the kingside.

23.♗f3 ♖bg8 24.g5 hxg5 25.♖xh8 ♖xh8 26.♘xg5 gxf5 27.♖g1 ♔f8 28.♕g2

The pieces are lined up, but the threats are still hardly overwhelming.

28...♘g4 But now they will be!

But now they will be!

29.exf5 ♘xh2

29...♖xh2+ 30.♕xh2 ♘xh2 was Black’s intention, I guess, but 31.♘h7+ ♔e8 32.♖g8 is mate!

30.♘h7+ 1-0

This also leads to mate! 30...♔e8 31.♕g8+ ♖xg8 32.♖xg8#.

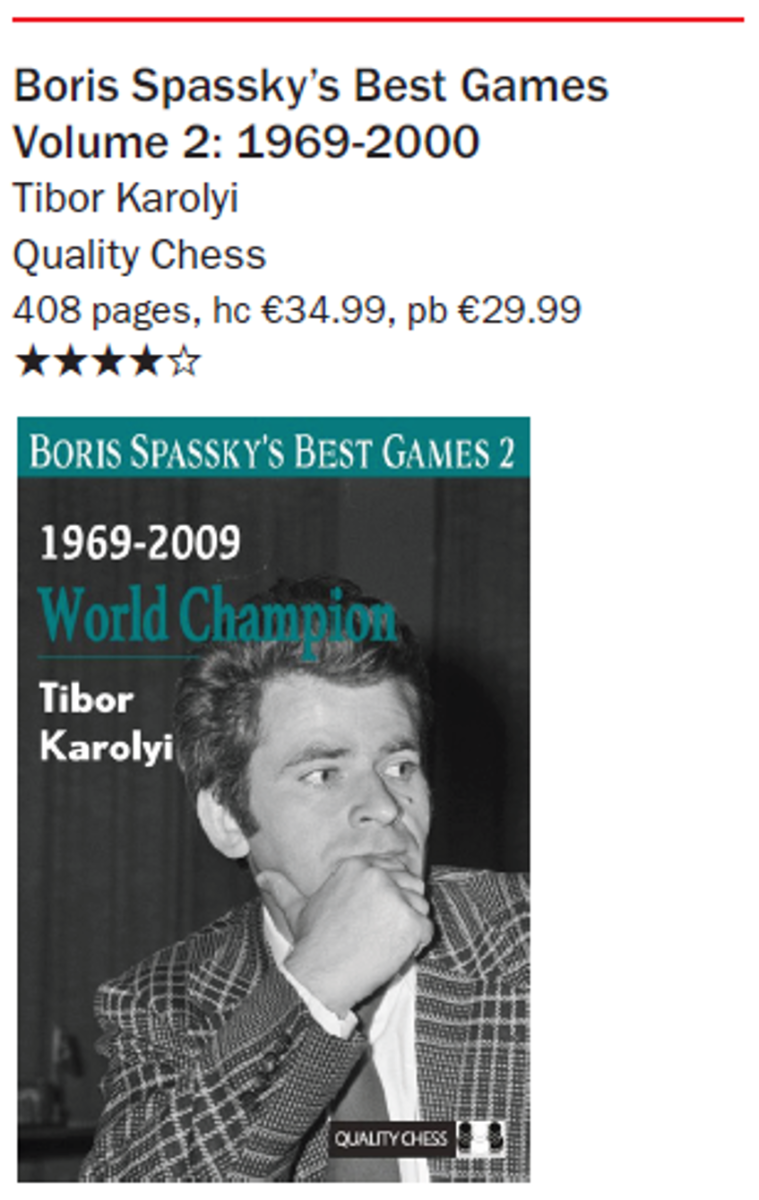

All in all, an interesting examination of a lesser-known facet of a great player’s style: 3 stars! Boris Spassky’s Best Games 2 1969-2000 by Tibor Karolyi examines the second part of the great Soviet player’s career, presented chronologically, with a chapter for each year. Karolyi does his usual excellent job of cycling through Spassky’s career and furnishing key games with detailed annotations while providing a few anecdotes along the way. I also liked his summaries of Spassky’s tournament and match results at the end of each chapter. In some ways, it must have been quite a difficult book to write. After the match against Petrosian in 1969, Spassky did not play much in 1970 and 1971; indeed, his first tournament in 1971 was only in July!

Boris Spassky’s Best Games 2 1969-2000 by Tibor Karolyi examines the second part of the great Soviet player’s career, presented chronologically, with a chapter for each year. Karolyi does his usual excellent job of cycling through Spassky’s career and furnishing key games with detailed annotations while providing a few anecdotes along the way. I also liked his summaries of Spassky’s tournament and match results at the end of each chapter. In some ways, it must have been quite a difficult book to write. After the match against Petrosian in 1969, Spassky did not play much in 1970 and 1971; indeed, his first tournament in 1971 was only in July!

Karolyi had already written a book on the immortal 1972 match against Fischer (Fischer-Spassky 1972 – Match of the Century Revisited) so only a summary of the match is presented in this book. And after the 1972 match, Spassky’s career became a strange story of games played at the very highest level interspersed with an ever-growing number of short draws and lapses of concentration. Probably 1977 – when he won the Candidates quarter-finals and semi-finals – and 1978 – when he shared first in the extremely strong Bugojno tournament – was the final period in which he still competed consistently at the very top level.

I always have a strange feeling when looking at Spassky’s career. It’s clearly ridiculous to view a player who became World Champion, was a World Championship Candidate on seven occasions (the last time in 1985 at the Montpellier Candidates tournament) and twice Soviet Champion as not quite having fulfilled his potential, but I can never shake that impression. For me, the quality of his best games is so high, and the manner of his victories so varied and versatile, that anything less than domination of his era feels like a disappointment!

Let me show you what I mean with this really lovely win out of nothing in the 1977 Candidates semi-final as Black against Lajos Portisch, who was possibly at his very peak.

Lajos Portisch

Boris Spassky

Geneva, Candidates semi-final 1977

Nimzo-Indian Defence

1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 e6 3.♘c3 ♗b4 4.e3 c5 5.♗d3 d5 6.♘f3 0-0 7.0-0 b6 8.cxd5 exd5 9.♘e5 ♖e8 10.♗d2

10.♗d2

I played the White side of this line a lot as a professional, and to avoid Spassky’s idea of ...♗a6, against the Canadian IM Bryon Nikoloff I came up with 10.♗b5 ♖e6 11.♘e2, to transfer the knight from c3 to f4 with tempo and at the same time leave the bishop on b4 hanging in thin air and vulnerable to trapping with a3. The irony is that after 11...a6 12.♗a4 c4 I thought that I stood clearly better as I had forced Black to release the central tension with ...c4. However, the engines consider this perfectly fine for Black and indeed after my continuation 13.♘g3 ♗b7 14.f4 b5 15.♗c2 ♗f8 16.♗d2 a5, they only see an advantage for Black! Always dangerous revisiting your old games with an engine, although I think such positions are quite easy to handle poorly as Black.

10...♗a6

I always worried that Black players would play this type of idea against me, but somehow I escaped! The exchange of light-squared bishops flattens out White’s position, removing any hope of a kingside attack.

11.♗xa6 ♘xa6 12.♕a4 ♕c8 13.♖fc1 ♕b7 14.♕c6 ♖ab8 15.♖c2 ♗xc3 16.♗xc3 ♘e4 17.♗e1 f6 18.♕xb7 ♖xb7 19.♘d3 cxd4 20.exd4 The position is balanced. Potentially Black might be able to claim the advantage of a good knight against a bad bishop tied down to the d4-pawn, but we are quite some way from that, as White has plenty of activity and his pieces are quite well-placed.

The position is balanced. Potentially Black might be able to claim the advantage of a good knight against a bad bishop tied down to the d4-pawn, but we are quite some way from that, as White has plenty of activity and his pieces are quite well-placed.

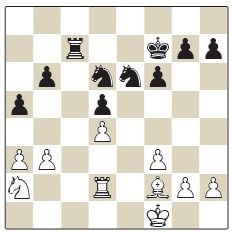

20...♘c7 21.f3 ♘d6 22.♗f2 ♘e6

I’m not sure I’ve ever seen knights like that before, but they are beautifully placed, attacking White’s weakest structural point, controlling central squares, and eyeing the outpost on c4.

23.♘b4 ♖d7 24.♖d1

24.♘xd5 ♘f5 25.♘c3 ♘exd4 26.♗xd4 ♘xd4 27.♖f2 would be my choice for a very even game, though the engines claim a slight advantage for Black. I imagine that Portisch was not yet looking for dead equality as White.

24...♔f7 25.♔f1

25.♘xd5 ♘b5 26.♘c3 ♘bxd4 27.♖cd2 ♖ed8 28.♔f1 would be even more equal!

25...♖c8 26.♖xc8 ♘xc8 27.♗g3 ♘e7

Spassky reshuffles his knights and the knight moves to f5 via e7.

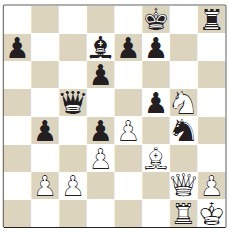

28.a3 ♘f5 29.♗f2 a5 30.♘a2 ♘d6

The knight moves back to d6 and threatens to invade on c4 winning a pawn.

31.b3 ♖c7 32.♖d2 The engine suggests a number of moves leading to Black’s advantage, but Spassky’s is beautiful and unusual.

The engine suggests a number of moves leading to Black’s advantage, but Spassky’s is beautiful and unusual.

32.♖c1 is suggested by the engines. It looks obvious, but it isn’t as obvious if you look a little deeper, as Black can win a pawn with 32...♖xc1+ 33.♘xc1 ♘b5 34.a4 ♘bxd4. However, after 35.♔e1 Black has a problem with his queenside pawns, as the knight on d4 cannot shield the b6-pawn forever and White threatens ♔d2-d3 to chase it away. After 35...b5 36.axb5 ♘xb5 37.♗b6 White wins the a-pawn and reestablishes material equality. Not easy!

32...♘b5 33.a4 ♘a3

A really lovely idea. The offside knight actually has two good follow-up squares on c2 and b1.

34.♗g3 ♖c6 35.♖d3

34.♗g3 covered f4 in order to prepare this move, which threatens to activate the miserable knight on a2 with ♘c3.

However, Black can prevent this beautifully!

35...♘b1

Another unexpected jump by the knight, threatening ...♖c2 and the knight on a2 is trapped.

36.♖d1 ♖c2 37.♖xb1 ♖xa2 38.♗f2 h5

Classic play: Black has many advantages on the queenside and now looks to expand his advantage across the whole board, starting by gaining a space advantage on the kingside.

39.♗e3 g5 40.h4 gxh4

An unexpected capture, not really done for the pawn but for the possibility of splitting open the white kingside pawns with ...h3.

41.b4 ♘g7

Another lovely knight redeployment! The knight will settle on f5, attacking d4 and eyeing the e3- and g3-squares.

42.♗f4 ♘f5 43.♔g1 ♘xd4 44.♗c7 h3

Here it is!

45.gxh3 ♘xf3+ From a6 to f3 in six moves!

From a6 to f3 in six moves!

46.♔h1 ♖xa4 47.bxa5 bxa5 48.♖b5 ♖c4 49.♗g3 ♔e6 50.♖xa5 ♘g5 51.♖a6+ ♔f5 52.♖d6 h4 53.♗h2 ♖c1+ 0-1

A wonderful game from Spassky!

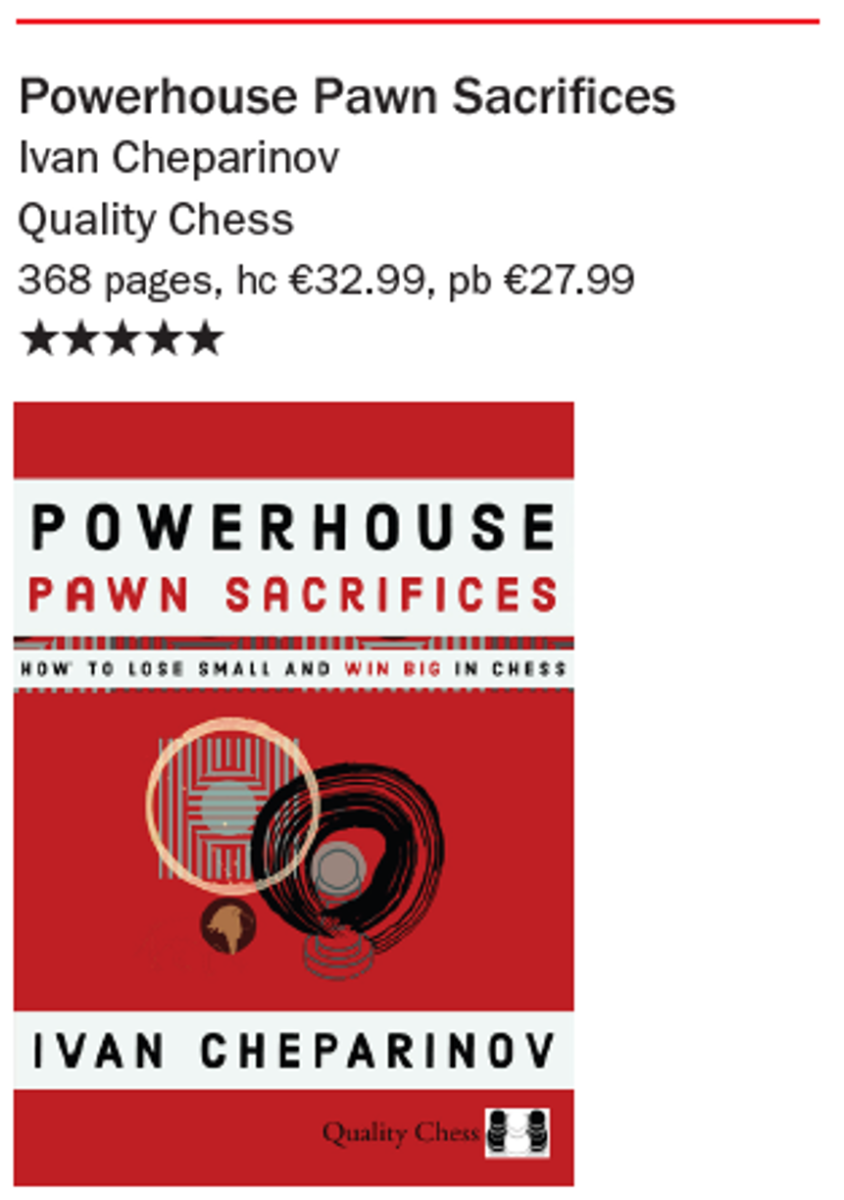

I enjoyed the book a lot as I nearly always do with Karolyi’s efforts: 4 stars! The final two books formed a pairing I just couldn’t resist: Powerhouse Pawn Sacrifices by Ivan Cheparinov and Converting an Extra Pawn in Chess by Sam Shankland. It reminded me of my favourite expression at work when explaining why an upgrade – while solving old problems – has also created fresh problems: the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away!

The final two books formed a pairing I just couldn’t resist: Powerhouse Pawn Sacrifices by Ivan Cheparinov and Converting an Extra Pawn in Chess by Sam Shankland. It reminded me of my favourite expression at work when explaining why an upgrade – while solving old problems – has also created fresh problems: the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away!

Both are excellent books, though definitely on the advanced side of chess. Cheparinov’s manual discusses the subject of pawn sacrifices for activity, first through two more general chapters entitled ‘Dynamics’ and ‘Long-term factors’ and then through opening-specific chapters: ‘Vienna’ (the Queen’s Gambit variety), ‘Catalan’, ‘Advance French’ and ‘Queen’s Indian’ before finishing on ‘How do the Greats do it?’. Funnily enough, the last chapter ends with two games of Veselin Topalov grabbing a pawn and surviving, which is a nice segue into Shankland’s book! I particularly liked the chapter on the Advance French, which deals with a type of long-term pawn sacrifice I first saw in engine games:

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.e5 c5 4.c3 ♘c6 5.♘f3 ♕b6 6.♗d3 cxd4 7.0-0 ♗d7 8.♖e1 ♘ge7 9.♘bd2 dxc3 10.bxc3 The e5-pawn is the only important pawn for White in this pawn structure, taking f6 away from the black pieces (thus making development of Black’s kingside pieces more laborious) and creating an outpost for a white knight on d6. Sacrificing a pawn in this way gives White’s pieces access to the active d4-square and the open b-file while the isolated c-pawn even gives White the lever c3-c4 against the black centre. In the good old days, it would have been enough to end this line with a sweeping gesture and the conclusion ‘with compensation’. Cheparinov shows through a mixture of analysis and illustrative games how concrete the play becomes at certain stages of the game, often when you would never really imagine it would need to be!

The e5-pawn is the only important pawn for White in this pawn structure, taking f6 away from the black pieces (thus making development of Black’s kingside pieces more laborious) and creating an outpost for a white knight on d6. Sacrificing a pawn in this way gives White’s pieces access to the active d4-square and the open b-file while the isolated c-pawn even gives White the lever c3-c4 against the black centre. In the good old days, it would have been enough to end this line with a sweeping gesture and the conclusion ‘with compensation’. Cheparinov shows through a mixture of analysis and illustrative games how concrete the play becomes at certain stages of the game, often when you would never really imagine it would need to be! Shankland’s book is composed of three chapters, each dedicated to a phase of the three-phase approach he describes for converting an extra pawn: ‘Stabilize’, ‘Make the Right Changes’ and ‘Plan for the Pawn’. I very much liked that last concept. I think it’s a common psychological error during practical games to lazily assume that the extra pawn will do the work for you. It’s important to actually think consciously about how your extra pawn can be woven into play appropriate to your position. Sometimes it’s as trivial as exchanging all the pieces off and creating a passed pawn in a pawn endgame but it can also be much more subtle than that.

Shankland’s book is composed of three chapters, each dedicated to a phase of the three-phase approach he describes for converting an extra pawn: ‘Stabilize’, ‘Make the Right Changes’ and ‘Plan for the Pawn’. I very much liked that last concept. I think it’s a common psychological error during practical games to lazily assume that the extra pawn will do the work for you. It’s important to actually think consciously about how your extra pawn can be woven into play appropriate to your position. Sometimes it’s as trivial as exchanging all the pieces off and creating a passed pawn in a pawn endgame but it can also be much more subtle than that.

This example from a Grischuk game impressed me a lot:

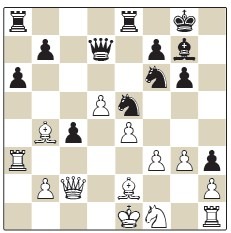

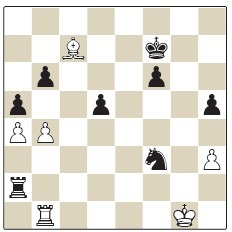

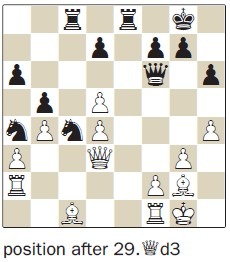

Alexander Grischuk

Michael Adams

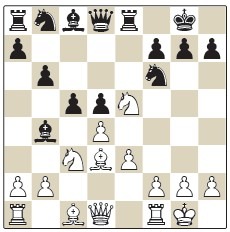

Calvia 2007 As Shankland explains, Black has sufficiently active pieces to equalize. But White still has chances for an edge if they come up with a plan which makes the extra pawn useful. What are the doubled d-pawns doing for White? They are restricting the black knights to some degree. For example, the d4-pawn is protecting the c3-square by blocking Black’s queen, as well as denying the c4-knight the e5-square. In fact, the knights are stuck on the queenside and rendered incapable of joining the fight on the kingside.’

As Shankland explains, Black has sufficiently active pieces to equalize. But White still has chances for an edge if they come up with a plan which makes the extra pawn useful. What are the doubled d-pawns doing for White? They are restricting the black knights to some degree. For example, the d4-pawn is protecting the c3-square by blocking Black’s queen, as well as denying the c4-knight the e5-square. In fact, the knights are stuck on the queenside and rendered incapable of joining the fight on the kingside.’

Michael’s next move made it much more difficult to create counterplay on the queenside, which gave Grischuk a free hand to mass on the kingside.

29...d6

29...♘cb6 was necessary, to create counterplay on the c-file, and would have been almost equal.

30.♖c2 ♖c7 31.♗e4 ♖ec8 32.♖e1 ♘ab6 33.♖ce2 ♖f8 34.h5 ♕d8 35.♕f3 ♘d7 36.♗d3 ♘f6 37.g4 Black has been unable to find a good defensive configuration and White’s kingside play has become unstoppable. Note once again how the extra doubled d-pawn prevents Black from adding defence to the kingside with ...♘e5.

Black has been unable to find a good defensive configuration and White’s kingside play has become unstoppable. Note once again how the extra doubled d-pawn prevents Black from adding defence to the kingside with ...♘e5.

37...♘b6 38.g5 ♖xc1 39.♖xc1 hxg5 40.♕f5 ♘bxd5 41.♕xg5 ♔h8 42.♔h2 ♕b6 43.♖g1 ♖g8 44.♕h4 a5 45.♗g6 1-0

Shankland concludes: ‘I quite like how Grischuk demonstrated the importance of building a plan that makes your extra pawn count. The extra pawn was doubled, so he could never hope to trade down to an endgame and make a queen. But the importance of his extra pawn was the focal point nonetheless. By restricting the black knights from coming to their king’s defense, the two white d-pawns played a decisive role.’

Very well explained!

The three-phase approach sounds quite simple to implement, but after working my way through the book, I wasn’t so sure. I’d seen so many obvious moves being wrong, and so many strange moves being right, that by the end I was mainly left feeling that chess is quite a complicated game! I almost missed Shankland’s Conclusion at the end, which sort of matches that feeling: ‘For anyone who has studied the preceding sections closely, you may find yourself asking something along the lines of “Okay how do I put this into practice? What rules and guidelines can I learn from having gone through these 29 games?” I hate to break it to you, but beyond a few nuggets of overall chess wisdom you may find scattered through the pages, there are no major guiding points that will suddenly turn pawns into points. My main hope is that by instilling the right thought process of breaking the conversion into three distinct phases, and then showing a lot of examples of each phase, both done well and done poorly, your instincts will have improved.’

Both Cheparinov’s and Shankland’s books had me smiling and saying, ‘that’s cool!’ at regular intervals, but I wasn’t quite sure what I’d picked up after the first careful read apart from lots of pleasure and hopefully some inspiration!

One thing I would say, though: if you want to make use of the exercises to test yourself, get someone else to put the positions on the board for you! With four diagrams on the page, I found it impossible not to sneak a peek ahead. The material in both books is of the highest quality, and I would highly recommend them to ambitious players looking to increase both the dynamism of their play and the solidity of their conversion technique. 5 stars for both! ■